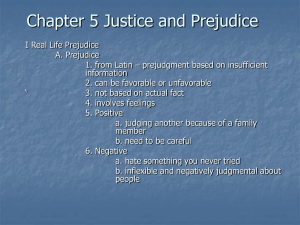

Prejudice: The Interplay of Personality, Cognition

advertisement