Prescription Drug Discount Cards: Current programs and issues

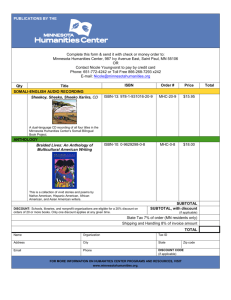

advertisement