1 Unit 3:1—Spectacle in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance

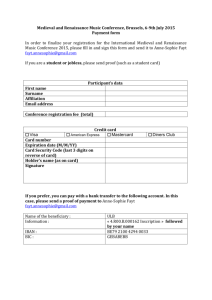

advertisement

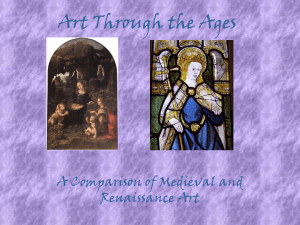

EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Unit 3:1—Spectacle in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance (Corpus Christi Festival) Introduction AUDIO CLIP: Click here to listen to Ordo Virtutum. You are listening to the Prologue from the Ordo Virtutum (The Play of Virtues) by Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179). Hildegard is one of the great figures of the Middle Ages. She was a Benedictine nun who was a writer of visionary revelations and scientific and medical treatises, a poet, composer, playwright, and powerful feminist voice in what was very much a man’s world. The Ordo Virtutum is her earliest, datable work—written in 1155. This music­drama is unique for its time because it deploys a cast of allegorical characters, and has a plot which, while spiritual in its orientation, owes nothing to the stories of the Bible. The play illustrates how the virtues operate on behalf of the soul in its struggle against the temptations of the devil. The play may have been written to be performed as part of the celebrations surrounding the consecration of Hildegard’s convent near the town of Bigen. The actors would have consisted of 20 nuns from the convent and a small male chorus of priests representing patriarchs and prophets. The audience would have consisted of the archbishop and clergy of Mainz, and the families of the nuns who founded the convent. The Ordo Virtutum is a sophisticated example of 12 th century Latin music­drama. It precedes, by approximately 75 years, the first efforts to establish a special church festival celebrating the redemptive power of the Eucharist: the Feast of Corpus Christi (festival of the Body of Christ). In this lesson we will examine the creation of the Corpus Christi Festival in the 13 th and 14 th centuries. The festival became one of the principal sites for the performance of religious dramas and the full flowering of medieval theatre. At the end of the lesson you will be able to browse through a collection of historic images of Medieval and early­ Renaissance performances. 1 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section A: The Doctrine of Transubstantiation To better understand the circumstances surrounding the establishment of the Feast of Corpus Christi, we need to step back and examine the Catholic Church’s doctrine of transubstantiation. Transubstantiation is the process of changing one substance into another. In the Catholic Church this change occurs in the Eucharist (the reenactment of the Last Supper in the sacrament of Communion) where the priest mysteriously converts bread and wine (the Host) into the literal body and blood of Christ. “The doctrine of transubstantiation was defined by the Lateran Council in 1215, and shortly afterwards the elevation and adoration of the Host were formally enjoined. This naturally stimulated the popular devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, which had been already widespread before the definition of the dogma.” ( http://97.1911encylopedia.org/C/CO/CORPUS_CHRISTI_FEAST_OF.htm) The physical action of elevating the Host and displaying it to the worshipers (a gesture known as Elevation) was a crucial moment in the celebration of the mass. The Elevation was thought to be the precise moment when the miracle of transubstantiation occurred. Seeing the Elevation was thought to bestow special grace upon the viewer. In the cities people ran from church to church to see the elevated Host as often as possible, since they assumed that the more Elevations you saw, the more grace you acquired. At the end of the twelfth century, stories began to circulate of miracles that had occurred at the moment of Elevation—people had seen visions, the Host shone like the sun, a tiny child had appeared in the priest’s hands and so forth. ( http://jerz.setonhill.edu/resources/PSim/yourkintro.html) This innovation in the celebration of the Mass took place at the same time the interior design of churches was changing. Larger churches were being built, altars were being made more elaborate and physically separated from the congregation through the installation of elaborate railings and screens—creating a more sacred, albeit isolated, playing space the clergy and choir occupied. The Elevation was an essential action so more people could see the Host and remain connected to the ritual. The Elevation was a grand, theatrical gesture that added to the sheer spectacle of the Mass. While it was necessitated, to a certain extent, by the enlargement of the churches, it was also part of an ongoing process of ornamenting Christian churches and theatricalizing worship services that had been taking place for hundreds of years. The Christian church was cautious and pragmatic in using the arts. Christianity was initially a simple, austere faith eschewing worldly pleasures for the glories of the hereafter. The arts were initially viewed suspiciously because of their association with pagan culture. Gradually, over time, all of the arts (architecture, sculpture, painting, music and drama) were used by the church as teaching aids for the illiterate masses. The church used the arts in a highly formalized manner—symbolically and emblematically to 2 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 ornament, decorate and embellish churches and the worship services. The Feast of Corpus Christi was part of this process. 3 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section B: The Dream of Juliana of Liege Early in the 13 th century, an Augustinian nun named Juliana of Liege was troubled by a recurring dream. The dream showed a moon in partial eclipse. Juliana came to understand the moon as a symbol for Christ’s glorious body (the Church) and the dark shadow as a figure lamenting the absence of a special feast in honor of the Eucharist. Juliana shared her vision and interpretation of it with Robert of Thourette, Bishop of Liege. The bishop was impressed by Juliana’s vision and in 1226 instituted a local festival in Liege after Juliana’s wishes. In 1264, Pope Urban IV—who as a young clergyman had served as a subordinate to Robert of Thourette—issued a papal bull (a special binding decree) as obligatory for the entire church. Unfortunately, adoption was slow and it wasn’t until the decree was reissued by Pope Clement V in 1311 that it was fully embraced by the Catholic Church. The feast was observed 60 days after Easter in late May or early­June. It celebrated the redemptive power of the Eucharist and was not a commemorative event like Easter or Christmas. The feast spread from Italy to France and throughout Europe, increasing in its popularity and splendor. The success of the festival is partially attributable to the emergence of a prosperous merchant class living and working in developing cities and towns. This merchant class invented capitalism, which was the dominant economic system. The merchants, and the guilds they founded, began to share political power and municipal authority with the nobility and church. The Feast of Corpus Christi allowed for and promoted secular participation in the festivities which were actively supported and funded by the merchant class. 4 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section C: Parts of the Festival The Feast of Corpus Christi developed gradually overtime and included the following events: Mass. Mass is the most important Catholic worship service with the Eucharist as its centerpiece. The Mass is inherently dramatic with its antiphonal singing, ritual re­ enactment of Christ’s Passion, readings from the Gospel, church vestments and properties, and cumulative and cathartic impact on the congregation. Pope Urban IV said the Mass should be a “glorious act of remembrance, which fills the minds of the faithful with joy at their salvation and mingles their tears with an outburst of reverend jubilation.” (http://jerz.setonhill.edu/resources/PSim/yourkintro.html) Procession of the Host. This is carried out of the church and traveled around the village or town for the adoration and meditation of the faithful. This was an opportunity for everyone in the community to see the Host without disrupting the other business of the mass. The procession became the climax of the Mass, symbolically extending it into the world of everyday reality. The procession included a spectacular litter or portable altar on which the host was displayed borne aloft on the shoulders of priests and lay­persons. Sometimes it included statues of saints, cherubs, and angels. Participating in the procession were the clergy and laity, members of the town council and representatives of the different trade guilds. The participants dressed in their most sumptuous and emblematic regalia—not unlike a graduation exercise, or the coronation of a pope or monarch. One’s costume and position in the procession usually reflected one’s place in the pecking­order of society. Other Celebrations. Rome gave local bishops the right to decide on “other celebrations” appropriate to the local community. This would frequently mean performances of religious plays. Drama had been used to embellish aspects of church ritual and services since the 10 th century. These musical­dramatic insertions (tropes) over time became more elaborate and, instead of being performed in Latin, began being performed in the vernacular language of the people. By the time the Feast of Corpus Christi was initiated, drama was an established and popular aspect of religious observances. The inclusion of dramatic performances allowed for direct, secular participation in the festival. Historians don’t know precisely when dramatic performances were first incorporated into the festival but by the late 14 th century (1300s) the Corpus Christi Festival had become the medieval world’s principal site for spectacular, dramatic performance presented, in some cases, over a period of several days (remarkably like the Greek’s City Dionysia over 1800 years earlier). Perhaps one reason dramatic performances were incorporated into the festival was because they served as a powerful public display of the piety and devotion of the community, even, on occasion, as a collective act of penance. This theory makes sense when you consider local festivals were being developed in the wake of the plague. 5 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section D: The Black Death The Black Death (Bubonic plague) arrived in Sicily in October 1347. Twelve Genoese galleys brought the infection to the port of Messina. Where the ships sailed from is unknown, perhaps from the Crimea or the Black Sea. Historians don’t know if the disease was borne by rats and fleas, or was already rampant among members of the crew. We do know that within a few days the plague had infected twenty members of the crew and had established a European beachhead. The plague would remain a fact of life in Europe throughout the 18 th century. The plague came in several virulent varieties. Its symptoms included the appearance of tumors and boils in the groin and armpits, “…some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an egg” (Philip Ziegler, The Black Death). Quickly the blackish tumors spread in all directions, discharged, and resulted in death within 5–7 days. The symptoms for another variety consisted of a continuous fever, dementia, hallucinations, and the spitting up of blood. In the 14 th century there was no real understanding of what caused the plague. Individuals who had access to classical Greek texts on medicine thought it was caused by “bad air” or swamp gases. The religious viewed it as God’s punishment provoked by the presence of heresy in the community, or blamed it on the Jews or Muslims. No one linked the spread of the disease to hygiene and dead rats in the streets. The initial results of the plague were absolutely devastating. Historians estimate that between 1347–1353 Europe lost one­third to one­half of its population. Over 1000 villages were deserted, never to be repopulated. The cemeteries in towns and cities were unable to provide space for all of the dead. Violence and crime spiraled out of control, and travel became dangerous. There were interruptions in the distribution of food and other supplies and certain areas experienced hunger and deprivation on a large scale. It is a historical fact that epidemics and wars can ironically result in some long­term societal benefits. In the case of the plague, it freed up a great deal of wealth in the form of land and capital that was redistributed. It contributed to the decline of the feudal or manorial system of governance and gave rise to a hardened, entrepreneurial mercantile class. Some historians trace the beginnings of the Renaissance to the post­plague years. The plague also had a profound impact on the arts. Powerful and graphic images of death were presented in painting, sculpture, and the drama. Death was presented as the “great leveler,” the grim reaper who no one could escape. The plague, in many ways, strengthened the message and authority of the church. It was the good Christian’s responsibility to be prepared for the sudden arrival of death and not be distracted by materialism. This is one of the great messages of religious drama. Interestingly, the plague also contributed to nourishing a worldlier, hedonistic spirit (“eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we die”) that would find its full force in the Renaissance. 6 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section E: Corpus Christi Dramas Mystery plays and cycle dramas were staged at the Feast of Corpus Christi. Today we define a “mystery” as something that is not or cannot be known, understood, or explained. In the Middle Ages, “mystery” meant something quite different. It comes from the Latin root mysterium meaning service or occupation. Mystery plays were those religious dramas produced by the trade guilds in a town or city. Mystery plays could consist of: 1) dramatizations of scripture, the life of Jesus and his family 2) stories of the lives and miracles of the saints and martyrs 3) allegorical dramas such as Hildegard von Bigen’s Ordo Virtutum Civic records reveal that different guilds had responsibility for presenting single plays that were parts of much larger dramatic performances that historians refer to as cycle dramas. Cycle dramas were a sequence of episodic plays—that usually started with the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and concluded with Christ’s passion and Judgment Day. They presented a Christian history of the world for medieval audiences. The authors of these plays were educated clerics and clerks who were deeply versed in the doctrines of the church. The plays were written to be presented by amateur performers in outdoor performance spaces for largely illiterate audiences. The dramatic performances were essentially large community festivals founded on a partnership that included the church, the municipal government, and the trade guilds. The church handled the delicate task of checking the script against authorized religious sources such as the Bible and Apocrypha. They provided musical support and some costume resources such as a bishop’s robe for the character of God. The city government provided the majority of the funding and materials necessary to present the festival (i.e. scaffolds for audience seating areas, law­and­order, etc.). The guilds were directly involved in sponsoring and presenting specific episodes (or individual mystery plays) in the large cycle dramas. Guilds would sometime assume responsibility for a play that was linked to the nature of the work the guild did. For example, the Shipwrights’ guild would be responsible for the story of Noah’s Ark and the Goldsmiths’ guild would be responsible for constructing Paradise. Generally, the guild was responsible for providing the scenery, props and costumes necessary for the play they were producing. All three groups (church, government, guilds) would provide actors for the productions. The actors were, by and large, men and boys—although there are some scattered references to women occasionally appearing in the productions. The actors were all amateurs, although surviving records indicate that some of the performers were paid. Fragmentary records indicate that the festivals had elaborate rules governing the conduct of the actors. Regular attendance at rehearsals appears to have been a problem, and a system of fines for absentees was sometimes implemented. Some festivals even had their actors sign contracts that spelled out their obligations such as agreeing never to be drunk at rehearsals. 7 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 The actual details of organizing the production were vested in a pageant­master who functioned as a quasi­director, producer, stage­manager, and prompter. The episodic nature of the scripts made the parceling out of responsibilities among the participants easy. Rehearsals normally took place over a two­month period preceding the festival, in April and May. Surviving records indicate that rehearsals were called early in the morning, at first light, before the start of the work day. Rehearsals were held in the largest room available (i.e. barn, town hall, church) and sometimes the guilds provided breakfast for their members who were involved in the rehearsals. No other occasion in the life of the community could promote a unity of purpose, self­ fulfillment, and egalitarianism as the Corpus Christi dramatic productions. The next lesson will focus on the performance spaces where the spectacles were presented. 8 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Images of Medieval and Early Renaissance Performance What follows is a collection of images of Medieval and early Renaissance performance. You may want to select one of these images as the subject of your second short essay which is due at the end of the third course unit. 1. Plan for the Lucerne market­place, Switzerland with spots marked out for the 1583 performance of the Mystery of the Passion. Donaueschingen Library. 2. Christ riding a donkey. Polychrome wood­carving from 13 th c. Zurich, Schweizerisches Landesmuseum. 3. General lay­out of the stage used for the Valenciennes Passion. Miniature from the Mystere de la Passion of Valenciennes, Paris. Bibliotheque Nationale. 4. The three kings, Flight into Egypt, Slaughter of the Innocents, Herod’s suicide from Valenciennes Passion. 5. Judas killing the son of Iscariot; Devil tempts Christ; Wedding­feast at Cana from Valenciennes Passion. 6. Jean Fouquet, Martyrdom of Saint Apollonia. Miniature from the Hours of Etienne Chevalier. Cluny, Musee Conde. 7. Hercules Furens. Miniature from the codex Vaticanus Urbinas 355, Rome, Vatican Library. 8. Roman theatre. Miniature. Frontispiece to the Terences des Ducs, Paris, Bibliotheque de l’Arsenal. 9. “Charivaris,” Miniature in the Roman de Fauvel, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. 10. Minstrel and girl playing for a lord. 13 th ­14 th c. miniature from Cancioneiro da Ajuda, Ajuda Library. 9 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Unit 3:2—Medieval Performance Spaces Introduction In this lesson we will examine the different performance spaces that were used for the presentation of religious plays in the medieval era and early­Renaissance. While people in this period lived among the physical ruins of the classical past, they did not use Greek and Roman amphitheaters as performance sites. Historical knowledge about the spectacles that had been staged there had vanished. More often than not, these ancient theatres and arenas were used as stone quarries for a ready supply of building materials, or as garbage dumps. For example, the seating areas for the Theatre of Marcellus in Rome were used as the foundation for apartment houses. 10 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section A: Church Interiors The earliest performance spaces were the interior of churches, convents, and monasteries—because this is where theatre first reemerged in the Middle Ages. When Christianity became the official religion of the late Roman Empire, the early church fathers were faced with a bewildering array of decisions to make. These included: where should they worship, what should a church look like, and how should it be decorated? The answers that the church fathers arrived at depended on their physical location and the resources they had at their command. The early church freely borrowed from Roman, Greek, Jewish, and Middle Eastern cultures and worship practices. Sometimes pagan temples—such as the Pantheon in Rome and the Parthenon in Athens were turned into Christian churches. A more common practice was converting large public buildings into churches. The most suitable type of building that could be put to this purpose was the basilica. Most Roman cities, of any size, had a basilica, which was a long rectangular building, located near the Forum that was used as a hall of justice or public meeting space. Basilicas had a large central hall (nave), flanked on either side by aisle­ways. Sometimes, basilicas had a semi­circular niche (apse) located at the far­end of the hall, opposite the main doorways. The basilica plan served as the starting point for all subsequent developments in ecclesiastical architecture. 11 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section B: Staging Tropes Early in the 10 th century, Christian worship services began to be embellished with insertions of mini­music dramas called tropes: from the Latin tropus meaning “added melody.” Tropes were expansions of the liturgy and consisted of three lines of sung or chanted dialogue. The Quem Quaeritis trope is the oldest surviving one and was performed as part of the early morning Easter service in monasteries and convents throughout Europe. The trope dramatizes the visit of the three Marys to the empty tomb of Christ: ANGEL: Whom do you seek in the sepulcher, people of Christ? MARYS: Jesus of Nazareth who is crucified, O heavenly one. ANGEL: He is not here; he is risen as he foretold. Go tell that he is risen from the sepulcher. Initially, this rudimentary dialogue was simply sung by the choir; soon though it was enacted by members of the clergy as part of the service. An intriguing 10 th century description of a performance survives in the Concordia Regularis. This was a rule book drawn up by Ethelwold, Bishop of Winchester, in England, providing instructions on how various religious services were to be conducted by the clergy. While the third lesson is being chanted, let four brethren vest themselves. Let one of these, vested in an alb [white linen robe worn by a priest], enter as though to take part in the service, and let him approach the sepulcher without attracting attention and sit there quietly with a palm in his hand. While the third respond is chanted, let the remaining three follow, and let them all, vested in copes [long cloak worn over an alb], bearing in their hands thuribles [censors] with incense and stepping delicately as those who seek something, approach the sepulcher. These things are done in imitation of the angel sitting in the monument, and the women with spices coming to anoint the body of Jesus. When therefore he who sits there beholds the three approach him like folk lost seeking something, let him begin in a dulcet voice of medium pitch to sing “Whom seek ye in the sepulcher, O Christian women?” And when he has sung it to the end, let the three reply in unison, “Jesus of Nazareth, the crucified, O heavenly one.” So he, “He is not here, He is risen, as He foretold. Go and announce that he is risen from the dead.” At the word of his bidding let those three turn to the choir and say “Alleluia! The Lord is risen!” This said, let the one, still sitting there and as if recalling them, say the anthem “Come and see the place.” And saying this, let him rise, and lift the veil, and show them the place bare of the cross, but only the cloths laid there in which the cross was wrapped. And when they have seen this, let them set down the thuribles which they bore in that same sepulcher, and take the cloth, and hold it up in the face of the clergy, as if to demonstrate that the Lord has risen is no longer wrapped therein, let them sing the anthem 12 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 “The Lord is risen from the sepulcher,” and lay the cloth upon the altar. When the anthem is done, let the prior, sharing in their gladness at the triumph of our King, in that, having vanquished death, He rose again, begin the hymn “We praise Thee, O God.” And this begun, all the bells chime out together. [A. M. Nagler, A Source Book in Theatrical History. New York: Dover, 1959; pp.39­41] The description contains all of the elements of theatre and spectacle. We have actors, an action, a magic space, and an audience. We have costumes (albs and copes), props (thuribles, palm frond, cross with a piece of cloth), and a setting consisting of a sepulcher or altar. Since Medieval churches were also burial grounds it is possible that an actual tomb could have been used as a staging area, although it is far more likely the altar area was used to suggest the tomb. The Concordia text is replete with stage directions for actors (“stepping delicately” to suggest the dainty walk of the Marys, “a dulcet voice” to suggest the celestial tones of an angel), and sound effects (“bells chime out together”) that punctuate the action. While no mention is made of lighting effects, small oil lamps and torches could have been used to provide dramatic, flickering illumination for the performance. The overall effect must have been very impressive in an English monastery in 975 A.D. All of the elements in this early church performance would be used in similar but more elaborate ways in later centuries. Mini­performances like Bishop Ethelwold’s Visit to the Sepulcher were used to enliven and enrich a variety of church services. Historians theorize that gradually these playlets became more elaborate and episodic and were performed in the naves of the churches. 13 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section C: Mansion­Platea Staging The diagram you are looking at a conjectural reconstruction of a medieval church setting from Richard Leacroft’s The Development of the English Playhouse. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1972; p. 3. The illustration shows the nave of basilica in which several different scenic stations have been positioned for the presentation of a cycle play. In the transept of the church, on a raised platform is a setting with a sepulcher that could be used for Bishop Ethelwold’s play. It is flanked, on either side and in the center of the nave, with a variety of other settings. This is an example of what historians call mansion­ platea staging. Mansion is Old French for “house.” The term is used to identify the scenic stations that represent the different locations in the play (i.e. paradise, hell, Galilee, etc.). The appearance of mansions varied. Some were elevated mini­stages, others were at floor level and defined by a single prop or object, and some were enclosed by curtains and drapes. They could be erected between the massive columns supporting the church’s roof, or they could be placed in the center of the nave. Normally mansions did not provide a complete scenic background; rather, through the use of selected props (i.e. throne, tomb, etc.), they suggested a locale. In the illustration, the structure near the center of the nave (in front of the Galilee fortress) is suggestive of the stable in a Christmas crèche (Nativity scene). In fact, the stable in a contemporary Nativity scene—either miniature or life­ size—is an excellent example of a mansion (with its roots squarely in the Middle Ages) that quickly establishes the location for the scene that is being depicted. Platea is Old French for “place” and refers to the open area around the mansions. While actors could be positioned within or in front of the mansions, the platea was a space the actors shared with the audience. It was a flexible, porous area that could be reconfigured from scene to scene; it could be both an extension of Caveman Bob’s “magic­circle,” or a space that spectators could safely observe the play from. In mansion­platea staging, the audience moved from mansion to mansion or place to place as the play progressed. In many respects, it was analogous in its spatial configuration to the layout of a modern fairground where each sideshow attraction or ride has its own display area that the audience moves in and out of. 14 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section D: Outdoor Performances The principals of mansion­platea staging were employed both in and out­of­doors for the presentation of religious dramas. Historians speculate that the performances were moved outside of the church to: 1) accommodate larger audiences 2) encourage the participation of a broader cross­section of the community 3) address the concerns of clergy who were uncomfortable with the performances inside the church and the amount of attention some clergy were devoting to them Outdoor performances were given in several different locations: in front of churches, in town squares, in old abandoned earthen­forts called rounds, and on mobile stages called pageant wagons. Church Exteriors. Church exteriors provided grand, inspiring backdrops for the presentation of cycle dramas. They were Christian versions of the elaborate facades on the skene buildings in Greek and Roman theatres. The different mansions would be set­up in a line a cross the front of the church. This is referred to as a “linear” or “simultaneous” setting. Town Squares. Medieval town squares were the urban equivalent of Caveman Bob’s camp fire. They were the commercial and governmental centers of civic life. They provided large, architecturally enclosed spaces that could be transformed into massive public arenas. City centers retain the potential for similar spectacular transformations today. Rounds. Rounds were old, pre­existing earthen forts; mostly found in England. They probably date from the time of the Roman occupation. During the Middle Ages, rounds were occasionally used for games/tournaments and for the performances of cycle dramas. There is scholarly conjecture on just how the rounds were used. One theory has the audience seated on the embankment with mansions erected around the circumference of the embankment and within the circular space in the center of the round that served as the platea. Other theories postulate other physical arrangements. Pageant Wagons. Mobile stages or pageant wagons are one of the most intriguing staging devices used for the presentation of religious dramas. A pageant wagon was a rudimentary version of a float in a parade. We know that pageant wagons existed— references survive in the inventory lists of guilds, and we have a few general descriptions. What we don’t have are reliable visual sources from the Middle Ages. All of our images come from the Renaissance. For example, Phyllis Hartnoll, in chapter two of our textbook, includes a lovely color illustration of “The Triumph of Isabella,” Brussels, 1615 (see Ill. 37, pp. 42–43), that shows a remarkable assemblage of spectacular pageant wagons that dwarf the teams of horses that are pulling them. Caution should be exercised in viewing these wagons as examples of Medieval pageant wagons. The appearance and 15 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 use of pageant wagons remains an item of debate among theatre historians. Based on the available evidence, historians conjecture: · Pageant wagons were used in large cities; they weren’t stable structures that were transported into the country­side over any great distance. · We don’t’ know if they were one or two stories high—the evidence is contradictory. · In England it appears that they were used to present certain cycle dramas. The wagons functioned as movable mansions that were pulled to predetermined locations where the scene/play was enacted. · In England and perhaps Flanders, pageant wagons were the property of the guilds that were responsible for their storage, upkeep, and decoration. · Physical action on pageant wagon stages would probably have been less energetic with scenes and plays presented in static locations. 16 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section E: Spectacle Cycle dramas, as they developed, were increasingly complex and expensive affairs. They were not presented every year; rather, towns and cities usually presented them on staggered intervals of anywhere between 2–10 years. The productions employed a great deal of visual spectacle. They had a version of the deus ex machina to lower cherubs and angels from heaven and stage miraculous ascensions. They used curtains to conceal and reveal surprising set pieces. The revelation of Paradise, for example, was usually a spellbinding moment; with hundreds of candles, oil lamps, and polished metal reflectors they created dazzling and inspiring celestial effects. Even more startling was the design and decoration of the entrance to Hell, which is often depicted as the expansive jaws of a gruesome monster spitting forth devils and sucking in sinners. Stage machinists took tremendous delight in creating terrifying depictions of Hell. They used fire works, realistic scenes of torture, and frightening sound effects to imaginatively suggest the mayhem, chaos, and suffering of Hell in spectacularly realistic ways. The medieval Hell Mouth is the forerunner of every “House of Horrors” (or similarly scary attraction) that can be found at modern fairs and carnivals. The costumes, like the scenery and props, varied considerably in appearance. They could be symbolic, emblematic, or very realistic. Without any real knowledge of historical style they were anachronistic in appearance, consisting of basic elements of contemporary dress with imaginative additions. If a character represented God or an angel they would appear in ecclesiastical attire like a bishop or a priest. If they represented a king or ruler, they would have a crown and royal robe. If they were a foreigner, they would wear something exotic—perhaps a turban from the Middle East. Humble characters, such as the shepherds in the Nativity scene, wore common peasant dress. The most spectacular costumes and masks were reserved for the demons and devils. Phyllis Hartnoll includes illustrations of a devil’s mask and costumes (Ill. 39, p. 45; Ill. 41 and 42, p. 47) in our textbook. We are still fascinated by monsters, ghouls, and demons, as anyone who has opened their door at Halloween can testify. Historian Andrea Gronemeyer makes an important point when she writes in Theater, “Like the graphic arts, the theater of the late Middle Ages focused more and more on empirical reality. The aim was to shore up the truth of Church doctrine with impressive theatrical effects. . . The tendency toward increasing realism strengthened the spectacular components of drama at the cost of the religious”(pp.41–12). This is true and was certainly part of the impetus for moving the plays out of the churches in the first place and into the community. Along with this increasing emphasis on spectacle, secular elements (characters and story lines) also began creeping into these devotional performances, both diluting and polluting their religious content. The death­knell for many of the vast cycle dramas was sounded in 1517 with the start of the Protestant Reformation in Germany. As the once universal Catholic Church 17 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 splintered into Catholic and Protestant camps, the old religious plays suddenly became controversial. Catholics wanted to continue performances while Protestants viewed them as Catholic propaganda and wanted them suppressed. In some cities and countries religious drama was suppressed because it was viewed as too political; in others it continued to survive but on a far more limited scale because of the expenses. In the last lesson in this unit we will examine the Oberammergua Passion Play which represents a living link to this dramatic tradition. 18 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section F: Video Clip To conclude this lesson I want you to view a brief scene from the National Theatre of Great Britain’s 1985 production of The Mysteries. The production was a conflation of the York and Wakefield cycles by the British poet/playwright Tony Harrison. In the space of nine­hours (or three three­hour performances if you chose to see it performed over a three­day period) audiences experienced a brilliant evocation of Medieval theatre. VIDEO CLIP: Click here to see a scene for the National Theatre of Great Britain’s production of The Mysteries. The plays were staged in a large rectangular, black­box theatre (not unlike the nave of a church) and employed mansion­platea staging. As you will see, audience members were in very close proximity to the actors and were reconfigured from scene to scene as the play progressed. The production emphasized the populist nature of Medieval theatre and the working­class culture that created it. It used anachronistic design elements to suggest medieval equivalents; for example God appeared on a forklift and the mouth of a steam shovel represented the entrance to Hell. The plays were written in a heavy North English dialect which may take your ears a few minutes to adjust to. I had the opportunity to see the original production in London, and it remains for me—in a lifetime of theatre going—one of the most astonishing plays I have ever seen. The episode you will be watching is the beginning of the story of Noah and the Ark. 19 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Unit 3:3—Jesters, Fairs, Processions, Masquerades and Tournaments Introduction AUDIO CLIP: Click here to listen to Salterello, an instrumental dance from 13 th c. Italy. What you are listening to is a 13 th century instrumental dance (“Salterello”) from northern Italy, performed on the fidele, the preferred instrument of the Middle Ages for the playing of dance music. The number has an energetic tempo that is quite different from the Gregorian chants which we normally associate with the period. Paralleling the development of religious drama in the Middle Ages were less formalized, but vigorous secular performance activities that enlivened and enriched popular culture. The origins of many of these secular performance activities can be traced to Europe’s pagan past. During the slow process of the Christianization of Europe, which lasted until at least 1000 A.D., the Church sometimes incorporated local pagan customs and celebrations into their calendar to win the hearts and minds of the people. Many of theses customs and activities were tied to the agricultural calendar. Consequently, many of our contemporary holidays and seasonal observances (i.e. Halloween, Christmas, Easter, etc.) have both Christian and pagan roots. Throughout the Middle Ages, as society became more politically and economically stable, there was a growing preoccupation with leisure time. Recreational activities reflect the resources, heritage, topography, interests, and time different groups of people in a community have at their disposal. In the Middle Ages (as is still essentially the case today) the peasantry had less opportunity for recreation than the middle class and the aristocracy. At the same time, recreational activities were embraced by all stratas of society. While some activities were exclusive and confined to certain classes, others cut across class boundaries and united communities. While these activities often had a civic or commercial purpose, they also functioned as a “Theatre of Social Recreation.” In this lesson we will examine the Theatre of Social Recreation as it is represented by jesters, fairs, processions, masquerades and tournaments. If you have not already read Timothy Husband’s introduction to Medieval Pageant (on e­reserve in the Library), I strongly recommend you do so now. It provides a very good introduction to this topic. 20 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section A: Jesters The court jester, with his colorful costume, elfin shoes, comic scepter, and pointed hood with bells, is one of the most popular images we have from the Middle Ages. Immortalized by Shakespeare in King Lear (in the character of the Fool) and Twelfth Night (in the character of Touchstone, the clown), you can’t attend a Renaissance Fair today without encountering a cloying troupe of them. The jester, over time, has become an iconic image: his figure is familiar to many of us as the Joker in a deck of cards. He is a “wild card,” a nimble shapeshifter that can change suits and be either high or low, depending on the rules of the game. The jester is a comic “Everyman” dressed in motley. We admire his facile wit; his ability to puncture pretense with his droll, sarcastic, and ironic comments, and—of course—his ability to tell a jocus (Latin for joke or verbal game). In many respects the jester is the classic outsider—visually marked by a costume which makes a spectacle out of him, but which serves as a license for him to make spectacles out of others. The tinkling bells we hear when he approaches hold both the promise and warning of mischief and delight. Romantically, we like to think of the jester as somehow being detached or apart from his surroundings—endowed like a seer with a special comic eye that allows him to see all of humanities’ follies and foibles, his mischievous grin masking a sensitive soul. His status as a professional fool empowers him to be outspoken when others must be circumspect. In a rigid, hierarchical environment he serves as a pressure valve—venting and letting off steam as entertainment. He is fearless and perhaps a bit reckless; just as likely to elicit a laugh as a groan, just as likely to be rewarded as punished for entertaining or offending his master. Jesters were the stand­up comedians of the Middle Ages. Some historians speculate that they represent the tradition of the itinerant entertainer reaching all the way back to the mimes of ancient Greece and Rome. This remains just a theory. We do know that by the beginning of the 13 th century some of these itinerant performers had gained a measure of respectability and security by being attached to the households of the aristocracy as servants. Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204), the wife of Henry II and mother of Richard the Lion­Hearted, is credited with introducing the fashion of having professional entertainers as part of a noble household to England. Jesters were simply one type of professional performer that found favor during the middle ages. Other entertainers included minstrels, troubadours, jongleurs, and minnesingers. Minstrels. Minstrels were professional musicians who sang or recited to the accompaniment of instruments. The root for “minstrels” is menials or ministerials, which denotes an entertainer attached to a noble house. Over time these entertainers set out on their own and performed at markets, fairs, private entertainments, and in Corpus Christi festival. Eventually, “minstrel” came to refer to any musician, singer, or poet. In the early decades of the 19 th century, in the United States, the term minstrel was used to describe musical and comic performance by troupes of primarily white men performing in black­face makeup as slaves. 21 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Troubadours. Troubadours were lyric poets who flourished in southern France, eastern Spain, and northern Italy from the 11 th century to the 13 th century. They wrote in Provencal (the language of the region), chiefly on themes of romantic love and gallantry. They were renowned for being “mighty sweet in their songs.” The poets themselves were educated individuals who were sometimes from noble families. In the 12 th –13 th centuries the term became more generalized in its meaning, and the entertainer who performed the poetry became also known as a troubadour. Read the two stanzas from Jaufre Rudel de Balaye’s 12 th century song When the nightingale among the leaves. When the nightingale among the leaves Gives and seeks and takes his love And moves his song of joy in joy And looks again so often on his mate; And the streams are clear and the meadows fair For the new delight which reigns therein A great joy comes to me, to dwell within my heart. For one companionship I long Because I know no richer joy Than this one: that she would be good to me In making me a gift of love. For she has a graceful form, soft and lovely And lacking any thing which ill befits it And her love is good to know. Jongleurs. These were men of common birth who worked as itinerant minstrels and entertainers. They sang songs, told stories, accompanied troubadours, and otherwise entertained people with whatever talents they were blessed with. The word sounds like “juggler,” which the jongleur could easily be (both literally and figuratively): someone who performs conjuring and feats of physical dexterity with different objects. Minnesingers. These were German lyric poets and singers of the 12 th – 14 th centuries; in many ways the German equivalent of the troubadour. Writers sometimes use these terms interchangeably to describe the wide variety of entertainers including musician, singers, dancers, acrobats, jugglers, animal trainers, jesters, clowns, and fools who could be found at this time in history. These were professional entertainers at a time when there really were no professional actors. While these entertainers performed for elite audiences in castles and manor houses, they also worked the streets (as entertainers still do), appearing at markets and fairs. 22 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section B: Markets and Fairs Markets were held on a daily or weekly basis and were local in their focus. Humbert de Romans writing in the 13 th century noted: “…markets are for lesser things, the daily necessaries of life; they are held weekly and only people from near at hand come. Hence markets are usually morally worse than fairs”(from Roy C. Cave and Herbert H. Coulson, A Source Book for Medieval Economic History, (Milwaukee: Bruce Pub., 1936), p. 124.) Fairs were more complicated and held less frequently for longer periods of time (weeks/months). Fairs were first of all national and international sites for commerce, but they also provided important opportunities for social recreation. The largest and most renowned fairs in Europe in the 12 th ­13 th centuries were the ten Champagne Fairs of France (the region, not the drink). Historians Francis and Joseph Gies captured the atmosphere of the fair when they wrote in Daily Life in Medieval Times, New York: Black Dog Publishers, 1990: The fair, though primarily a wholesale and money market for big business, is a gala for common folk. Peasants and their wives, knights and their ladies, arrive on foot, on horse, on donkeys, to find a bargain, sell a hen or a cow, or see the sights. Dancers, jugglers, acrobats, bears, and monkeys perform on street corners; jongleurs sing on church steps. Taverns are noisily thronged. The whores, amateur and professional, cajole and bargain. For a farmer or backwoods knight, the fair is an opportunity to gape at such exotic foreigners as Englishmen, Scots, Scandinavians, Icelanders and Portuguese […]Most numerous are the Flemings and the “Lombards,” a term which includes not only men from Lombardy, but Florentines, Genoese, Venetians and other north Italians. The rustic visitor hears many languages spoken, but these men of many nations communicate with little difficulty. Some of the more learned know Latin, and there are plenty of clerks to translate. But the lingua franca of the fairs is French; though there is little sense of French nationality, and though French is not universally spoken throughout the narrow realm of the king of France, nearly every merchant and factor at the fair can acquit himself in this tongue. (p.341) Commerce and entertainment have gone hand­in­hand throughout history. While markets and fairs provided venues for entertainers to work, the concentration of merchants and customers and the display of goods (bolts of colorful cloth, spices, wine, sugar, grain, meat, cheese, lacquer, dyes, etc.) created a special spectacle of their own. Enterprising merchants employed the basic principals of design to create eye­catching displays of their goods to attract customers and promote sales in the same way that merchants do today. The art/craft of window dressing may well have been created in these open air fairs in the Middle Ages. Section C: Processions 23 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Processions and pageantry, whether religious or civic, were important forms of social recreation in the Middle Ages. They were public displays of power and authority “frequently laden with polemical and propagandistic intent” (Medieval Pageant, p.5). Like the Corpus Christi procession, they were sites for the display of spectacle. Timothy Husband, in his introduction to Medieval Pageant, discusses several different types of processions, including royal entries and funerals. These were very special events in the life of a community—by no means everyday occurrences. Presented below are two visual examples of these events. Both of these illustrations come from manuscript illuminations of the period. Illuminations provide us with some of the most vivid visual images of medieval life that have come down to us. Royal Entry: Isabeau of Bavaria entering Paris (Illumination from Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, 15 th century). Isabeau of Bavaria, the eighteen­year­old wife of King Charles VI, enters Paris to be crowned queen of France in 1389. Paris gave her the most splendid reception yet accorded a foreign princess, with tournaments, dances, pageants and masquerades. Festive tapestries and cloth of gold lined the route and among the attractions was a fountain spouting spiced wine, served in gold goblets by ‘sweetly singing maidens’. The illustration shows the queen approaching the Porte St­Denis, where dignitaries of church and state (and the king’s jester on the wall) await her. She is riding in a litter carried by two horses, under a canopy decorated with Fleur­d­lies (the traditional heraldic device of the French monarchy). Fleur­d­lies decorate many of the banners and decorations in the scene. The queen­to­be is accompanied by members of the nobility to fanfares from heralds positioned above the city gates. In the background are the Sainte­Chapelle and the cathedral of Notre­Dame. Royal Funeral: Funeral procession of Charles VI (Illumination from the Chroniques de Charles VI, French 15 th century). Charles VI of France died in 1422 and was buried with his ancestors at St­Denis. This miniature shows the funeral procession leaving Paris. On the bier lies a richly dressed effigy of the dead king. The robe the effigy wears and the pillow it reclines on are decorated with Fleur­de­lis. Life­like funeral effigies were used in royal funerals throughout Europe well into the 18 th century. The mourners wear black but the chief mourner, the Duke of Bedford, and members of the Parliament of Paris wear red because the king never dies—“the king is dead, long live the king!” While royal entries and funerals may seem distant to us in the 21 st century—civic processions are an important part of the ceremonial life of our country. The spectacle of former President Regan’s funeral in 2004 and the pageantry of the Presidential Inauguration in 2005 are just two examples of this. 24 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section D: Masquerades The making and wearing of masks in ritual performances is ancient and a fundamental part of performance traditions in most cultures. Masks conceal identities, freeing the wearers from societal constraints and social inhibitions. Masks can also magically transform the wearer into the spirit, god, animal, or character represented by the mask. Throughout Europe, in the Middle Ages, masks and disguises were worn in folk and religious festivals. In England, masking became known as Mumming. While its origins are obscure, Mumming remains associated with Lent, Christmas, and New Year’s Day festivities in many parts of the world. For example, Philadelphia sponsors a huge Mummers Parade each January. WEBSITE: If you are not familiar with this contemporary city­wide masquerade you may want to visit the Philadelphia Mummers Parade web­site: http://mummers.com/ In the Middle Ages, mumming coupled masks and disguises with processional visits where groups of mummers (usually troupes of men) visited homes soliciting (and occasionally giving) gifts of food and drink. The acts of visitation and solicitation led to improvised monologues and dialogues between those participating in the masquerades. The calls of masked children on Halloween night: “Trick or treat; money or eats” or “Trick or treat, smell my feet, give me something good to eat” are contemporary counterparts to this. By the 17 th and 18 th centuries brief, scripted mummer’s plays had developed in England from this improvisational activity. Historians speculate that masking became a popular social activity with the nobility who combined it with song, dance, and scenic decoration to create elaborate disguising and masquerades. Contemporary costume parties, masked balls, Mardi Gras, Mummers Parades, and Halloween are all contemporary manifestations of this ancient impulse. 25 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Section E: Tournaments Tournaments probably started in northern France near the end of 11 th century—although some sources date the activity as far back as the 9 th century. They were public contests of courage and skill that were the medieval equivalent of gladiatorial combats. They were inspired, to a certain extent, by an antiquarian interest in Roman war­games and were essentially training for war. Richard Barber and Juliet Barker in their authoritative Tournaments: Jousts, Chivalry and Pageants in the Middle Ages (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989) provide the following description of an early tournament: The tournament, in its strictest sense, was a melee fought out over several miles of open countryside encompassing rivers, woods, vineyards and farm buildings—all of which provided useful opportunities for ambush and sortie. The boundaries were unmarked in the early days, though the field was vaguely designated by references to two towns: tournaments were thus proclaimed ‘between Gournai and Ressons’, for example, or ‘between Anet and Sorel’. The only formal limits were certain specially designated areas which were fenced off as refuges where knights could rest or rearm in safety during the combat. Several companies of knights took part, under the leadership of the same lords whom they followed and served in warfare, and often as many as two hundred knights participated on each side. At this early period there were no rules to distinguish the tournament from real battle: there were no foul strokes or prohibited tactics and, even if there had been, there was no­one to supervise or enforce them. It was thus quite common for several knights to band together to attack a single tourneyer: there were instances of tourneyers being attacked despite the fact that they had lost vital parts of their armour in the skirmishes and occasions on which any weapon to hand was used—including bows and arrows and crossbows. The only concessions to the sporting nature of the combats were the provision of refuge and the sine qua non that the object of the game was to capture and ransom the opposing knights, not to kill them. Here was a rough and tumble game which was so strongly imitative of battle that it often became indistinguishable from it […]. (14­15). Barber and Barker’s description of tournament is quite different from the romantic image of pairs of knights in armor fighting to win the love of ladies fair that has come down to us in Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, E. B. White’s The Once and Future King, and cinematic spectacles inspired by the Arthurian legend. Gradually, over time, the tournament assumed a more formal and ritualized structure designed to perpetuate and enhance chivalric values. The tournament is the first sport for which detailed rules and regulation survive: from its history emerges the concept of “fair 26 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 play,” and the word itself—tournament—survives as a description of many of today’s sporting events. By the 13 th century tournaments were regulated in the field by governments and were being associated with the romantic aspirations found in the secular literature of the period. In the later part of the 13 th century ladies began attending tournaments and their presence helped to associate the tournaments with the cult of courtly love and a growing nostalgia for knighthood’s glory days. Tournaments, while still quite violent, also became somewhat more genteel with the use blunted lances and swords. Finesse and horsemanship won out over brute force. Finally, it is important to realize that gun powder is first used in European warfare in the 14 th century, and when this occurs, the heroic armored knight on horseback eventually becomes obsolete. Three types of tournament combat eventually developed. They were: 1) The joust, which consisted of two armored knights on horseback opposing each other with lances. The object of the combat was to knock your opponent off their horse which was hard to do because the back of the saddle was about a foot tall. The knights charged each other from opposite directions, only separated by a low fence (eventually this fence would be eliminated). Once someone fell off they were usually hurt or killed. Knights would either forfeit their horse and armor, or if they were able, fight on the ground with a sword and shield. Incidentally, suits of armor which could weigh upwards of 50 pounds severely restricted a knight’s sight and mobility. 2) The melee, which was a slightly more organized and safer version of the original tournament. The melee consisted of two teams with flags on their backs and armed with clubs and blunt swords. The melee could occur in a meadow or corral set up in a town square. The object in the melee was to knock the flags off. 3) Foot combat which pitted dismounted knights against one another. This was closest in spirit to the gladiatorial fights. Tournaments and jousts survived as princely entertainments into the 17 th century. Some of the spectacle and excitement of tournaments in the late middle ages and early Renaissance is captured effectively in engravings and illuminations from the period. 14 th century illumination from Manesse Anthology (Universitatsbibliothek, Heidelberg, MS Cod. Pal. Germ 848, f. 17). In this illumination the dukes of Anhalt engage in a melee with swords. Two of the knights appear to have their opponents in head­locks—reminiscent of wrestling moves. The knights wear chain­nail armor and helmets. The combat is being observed by ladies who appear to be engaged in animated conversation. It is unlikely that the outcome of the melee will be fatal because ladies are present and the sword blades have been blunted. 27 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 1506 engraving by Lucas Cranach (Radio Times Hulton Picture Library, London). The physical set­up and chaos of a melee in a market square can be seen in Cranach’s engraving. The spectators are separated from the melee by a simple barrier which they lean on to watch the proceedings Jousts at Smithfield before Richard III in 1394 (Lambeth Palace Library MS 6, f. 233). The artist imagined this scene approximately a century after it occurred. The armor and conventions of the joust belong to the 15 th century rather than the 14 th century. Tournament in front of King Arthur (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 383 f. 16). This is an imagined scene by a Flemish artist set in the age of the legendary King Arthur. The jousting is in its second stages, a duel with swords, and discarded lances are strewn around the arena 28 EA/Unit 3 master_Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.doc Friday, November 04, 2005 Unit 3:4—Oberammergua Passion Play Introduction On February 25, 2004 (Ash Wednesday), Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ opened nation­wide in movie theatres. The film was shrewdly promoted with advanced screenings for selected clergy (including the Pope!) and a barrage of news stories, which generated considerable interest in the film before it opened. When the film did open it received mixed reviews, being criticized for both its violence and the depiction of Jews. Despite what the critics and pundits had to say, the movie resonated with popular audiences and “stunned Hollywood by taking in $370.3 million at the box office” ( http://www.usatoday.com/life/movies/news/2004­07­21­passion­dvd­discount_x.htm). Gibson’s film is only the latest in a long line of cinematic and stage renditions of the Passion that extend back to the Middle Ages. By far, the oldest, continuously performed stage version of the Passion is the Oberammergua Passion Play which was first presented in the small village of Oberammergua, Germany, in 1634. Since then it has been produced once every decade. The year 2000 marked the 40 th production of the play which has become a huge, international theatrical event. The next production will occur in 2010 with tickets going on sale in 2008. 29