AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline I. Learning Objectives—In

advertisement

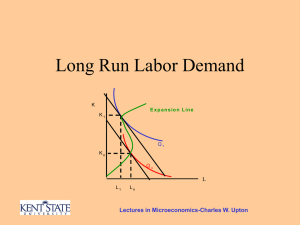

AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline I. Learning Objectives—In this chapter students should learn: A. Why labor productivity and real hourly compensation track so closely over time. B. How wage rates and employment levels are determined in competitive labor markets. C. How monopsony (a market with a single employer) can reduce wages below competitive levels. D. How unions increase wage rates and how minimum wage laws affect labor markets. E. The major causes of wage differentials. F. The types, benefits, and costs of “pay‐for‐performance” plans. II. Labor, Wages, and Earnings A. Wages refer to the price paid for labor (blue‐collar, white‐collar, professionals, and small business owners, in terms of the labor services they provide in operating their businesses). B. Wages may take the form of salaries, bonuses, commissions, or royalties, and benefits such as paid vacations, health insurance, and pensions. In this text, the term “wages” means all such payments and benefits per hour. C. It is important to distinguish between nominal and real wages. 1. The nominal wage is the amount of money received per hour, day, or year. 2. The real wage is the “purchasing power” of the wage (the quantity of goods and services that can be obtained with the wage). a. One’s real wage depends not only on one’s nominal wage, but also on the price level of the goods and services that will be purchased. b. If the nominal wage rises by 5 percent and inflation is 3 percent, the real wage rose only by 2 percent. 3. This discussion assumes that the price level is constant, so the term “wages” is used in the sense of “real wages.” III. The General Level of Wages A. Wages differ greatly among nations, regions, occupations, and individuals (Global Perspective 13.1). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline B. Productivity plays an important role in determination of wages. American wages have been high historically and have risen because of high productivity. There are several reasons for this high productivity. 1. Capital equipment per worker is high—approximately $118,200 per worker in 2008. 2. Natural resources have been abundant relative to the labor force in the United States. 3. Technological advances have been generally higher in the United States than in most other nations, and work methods are steadily improving. 4. The quality of American labor has been high because of good health, education, and training. 5. Other less tangible items underlie the high productivity of American workers: a. Efficient, flexible management b. A stable business, social, and political environment that emphasizes productivity c. The vast size of the domestic market, which allows for economies of scale d. Increased specialization of global production facilitated by free‐trade agreements B. Real wages increase at about the same rate as output per worker (Figure 13.1). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline C. Real wages have increased in the long run because increases in labor demand have outstripped increases in labor supply (Figure 13.2). IV. A Purely Competitive Labor Market B. Characteristics 1. Numerous firms competing to hire a specific type of labor. 2. Many qualified workers with identical skills supply this type of labor. 3. Individual firms and individual workers are “wage takers;” neither can control the market wage rate. C. The market demand is determined by summing horizontally the labor demand curves (the MRP curves) of the individual firms (Figure 13.3a Key Graph). C. The market supply is determined by the amount of labor offered at different wage rates. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline 1. More labor will be supplied at higher wages, so labor supply is an upward‐sloping curve. 2. The wage must increase to attract more workers away from alternative uses of time spent in other labor markets, household activities, or leisure. D. The market equilibrium wage and quantity of labor employed will be where the labor demand and supply curves intersect; in Figure 13.3a (see prior page), this occurs at a $10 wage and 1,000 employed. 1. For each firm, the MRC is constant and equal to the wage, because the firm is a “wage taker” and alone has no influence on the wage in the competitive model (Table 13.1). 2. Each firm will hire workers up to the point at which the market wage rate is equal to the MRP of the last worker hired (MRP = MRC rule). V. The Monopsony Model A. Characteristics 1. There is only a single buyer of a particular kind of labor. 2. The workers providing this type of labor have few options other than working for the monopsony, because they are geographically immobile or must acquire new skills to find other jobs. 3. The firm is a “wage maker,” because the wage rate it pays varies directly with the number of workers it employs. B. Complete monopsonistic power exists when there is only one major employer in a labor market; oligopsony exists when there are only a few major employers in a labor market. (Note: the root “sony” means “to purchase,” whereas the root “poly” means “to sell.”) 1. The labor supply curve will be upward sloping for the monopsonistic firm; if the firm is large relative to the market, it will have to pay a higher wage rate to attract more labor. 2. As a result, the marginal resource cost will exceed the wage rate in monopsony, because the higher wage paid to additional workers will have to be paid to all of the workers hired earlier. Therefore, the MRC is the wage rate of an added AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline worker plus the increments that must be paid to others already employed (Table 13.2). 3. Equilibrium in the monopsonistic labor market will also occur where MRP = MRC, which determines the quantity of workers hired. The wage is found by drawing a vertical line directly down to the supply curve (Figure 13.4). 4. In a monopsonistic labor market, fewer workers will be hired and they will be paid a lower wage than would be the case if that same labor market were competitive, other things being equal. In the same way a monopoly restricts output in order to raise the price and maximize profit, the monopsony restricts hiring restricts employment in order to lower the wage and increase profit. 5. Nurses are paid less in towns with fewer hospitals than in towns with more hospitals. In professional athletics, players’ salaries are held down as a result of the “player drafts” that prevent teams from competing for the new players’ services for several years, until they become “free agents.” AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline VI. Three Union Models A. Demand‐Enhancement Model—unions prefer to raise wages by increasing the demand for labor (Figure 13.5). 1. Unions try to increase the demand for the product they produce by lobbying for government contracts, funding, or trade barriers, or by making appeals to the public to buy American‐made (or union‐made) products. 2. Unions may try to increase the price of substitute resources, thus increasing the demand for union workers (e.g., a higher minimum wage). 3. Unions can support public actions that reduce the price of a complementary resource, such as utility prices. B. Exclusive or Craft Union Model—unions raise wages by restricting the supply of workers (Figure 13.6). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline 1. Unions can reduce the number of qualified workers by requiring large membership fees, long apprenticeships, or limiting the number of people admitted to the profession. 2. Occupational licensing requirements are another way of restricting labor supply in order to keep wages high. Nearly 600 occupations are licensed in the United States. C. Inclusive or Industrial Union Model—unions do not limit membership, but try to unionize every worker in the industry (Figure 13.7). 1. The union can threaten to withhold the entire labor supply through a strike, so it has the power to impose a higher wage than the employers would otherwise pay. 2. The negotiated wage becomes the employer’s MRC between point “a” and point “e.” 3. Unemployment results, as the quantity of workers supplied at the negotiated wage is greater than the quantity of workers demanded at that wage. D. Employers will pay union members higher wages (15% higher, on average) and hire fewer workers than they would if the workers were free to accept a lower wage. VII. Bilateral Monopoly Model A. Occurs when a monopsonist employer faces an inclusive labor union; both the employer and employees have monopoly power. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline B. The firm will hire the quantity of workers where MRP = the wage, but the wage is indeterminate and will depend on negotiation; the side with more bargaining power is likely to get the wage closer to what it seeks (Figure 13.8). C. A bilateral monopoly may be more desirable than one‐sided market power. If a competitive market does not exist, it may be more socially desirable to have power on both sides of the labor market, so that neither side exploits the other. VIII. The Minimum Wage Controversy A. Minimum Wage Facts 1. The federal minimum wage was implemented with the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. 2. The federal minimum wage has ranged between 30 and 50 percent of the average wage paid to manufacturing workers. 3. Numerous states have minimum wages exceeding the federal minimum wage; in 2010, the state of Washington had the highest at $8.55 an hour. B. The Case against the Minimum Wage 1. The minimum wage forces employers to pay a higher than equilibrium wage, so they will hire fewer workers as the wage pushes them higher up their MRP curve (Figure 13.7). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline Workers would be better off earning a lower wage than losing their jobs. 2. The minimum wage is “poorly targeted” to fight poverty; some minimum wage workers are teens or are from affluent families who do not need protection from poverty. C. The Case for the Minimum Wage 1. Minimum‐wage laws occur in markets that are not competitive. In a monopsonistic market, the minimum wage increases wages with minimal effects on employment. 2. Increasing the minimum wage may increase productivity. a. Managers will use workers more efficiently when they have higher wages. b. The minimum wage may reduce labor turnover and, as a result, training costs. D. Evidence and Conclusions 1. The unemployment effects do not appear to be as great as critics fear. 2. Because many who are affected by the minimum wage are not from poverty families, the minimum wage is not as strong an antipoverty tool as many supporters contend. 3. More workers are helped by the minimum wage than are hurt. 4. The minimum wage helps give some assurance that employers are not taking advantage of their workers. IX. Wage Differentials A. Table 13.3 illustrates substantial differences among wages in several occupations. B. Wage differentials can be explained by supply and demand. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline 1. Given the same supply conditions, workers in a market with a strong demand will receive higher wages; given the same demand conditions, workers in a field with a reduced supply will receive higher wages (Figure 13.9). 2. Demand—the worker’s contribution to the employer’s total revenue (MRP) depends on the worker’s productivity and the demand for the final product (Figure 13.9a and b). 3. Supply—workers are not homogeneous; they are in noncompeting groups. a. Ability levels differ among workers; those with higher skills are low in supply and can negotiate a higher wage (Figure 13.9c – see next page). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline b. Education and Training (Investment in Human Capital) i. Human capital is the accumulated knowledge, know‐how, and skills that enable a worker to be productive and earn income. ii. Workers with higher education earn higher incomes because the supply of workers is lower and the workers are more productive (Figure 13.10). iii. CONSIDER THIS … My Entire Life—workers with a great deal of skill can command high wages because of previous investment in education and training. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline b. Compensating differences—the nonmonetary aspects of the job may make some jobs preferable to others because of working conditions, location, or other positive or negative aspects of the job. Employers must pay higher wages to attract workers into jobs with highly negative aspects (Figure 13.9c and d). C. Market Imperfections 1. Workers may lack information about alternative job opportunities. 2. Workers may be reluctant to move to other geographic locations. 3. Artificial restraints on mobility may be created by unions, professional organizations, and governments. 4. Discrimination (occupational segregation) may crowd women and minorities into certain labor markets, lowering wages in those markets and raising wages in others. X. Pay for Performance A. The Principal‐Agent Problem 1. Both the workers and the firm want the firm to survive and be profitable. 2. Workers will act to improve their own well‐being, often at the expense of the firm, including shirking on the job, taking unauthorized breaks, checking personal e‐ mail and playing computer games at work, and generally not working as hard as they might. 3. Firms can reduce or eliminate shirking by hiring more supervisors, but monitoring is difficult and costly. B. Incentive pay plans tie worker compensation more closely to worker output or performance. 1. Piece rates—workers are paid according to the quantity of output produced. 2. Commissions and royalties—workers are paid a percentage of the value of their sales. 3. Bonuses, stock options, and profit sharing are other ways to motivate workers to have the same interests as the firm. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 13 Outline 4. Efficiency wages—workers are paid above‐equilibrium wages to encourage extra effort. The firm achieves greater efficiency from higher‐quality workers, higher morale, increased productivity, and lower recruitment and training costs because of reduced turnover. C. Pay for performance can help overcome the principal‐agent problem and enhance worker productivity, but such plans can have negative side effects. 1. A rapid production pace can compromise quality and endanger workers. 2. Commissions may cause salespeople to exaggerate claims, suppress information, and use other fraudulent sales practices. 3. Bonuses based on personal performance may disrupt cooperation among workers. 4. Less energetic workers can take a “free ride” in profit‐sharing firms. 5. Stock options may prompt unscrupulous executives to create a false appearance of higher profit, in order to raise stock prices and personally profit. 6. Firms paying “efficiency wages” may have fewer opportunities to hire the new workers who could bring creative energy to the workplace. XI. LAST WORD: Are Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) Overpaid? A. Multimillion‐dollar salaries of top corporate executives are highly criticized. B. CEO pay in the United States ($2.2 million average for firms with $500 million in sales) in 2005 was almost twice that of France and Germany ($1.2 million), and nearly four times that of South Korea and Japan. C. Supporters of high CEO compensation argue that executive decisions affect the productivity of all employees in a firm, as well as others who aspire to achieve a position as a CEO. Because the supply of these people is very limited and their MRP is very high, they can command very high wages. D. Critics contend that although CEOs deserve higher pay than ordinary workers, the gaps are excessive and bear little relationship to MRP. (They would especially balk at CEO performance bonuses at times of wage and salary freezes or cuts for ordinary workers.) They also believe that the high salaries are unfair to stockholders; Boards of Directors exaggerate the importance of the CEO and thus overcompensate, reducing company profits and potential dividends for investors.