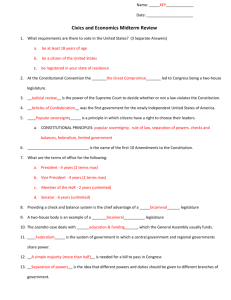

Marbury V. Madison Case Brief Summary

advertisement

Marbury v. Madison – Case Brief Summary Summary of Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137, 1 Cranch 137, 2 L. Ed. 60 (1803). Facts On his last day in office, President John Adams named forty-two justices of the peace and sixteen new circuit court justices for the District of Columbia under the Organic Act. The Organic Act was an attempt by the Federalists to take control of the federal judiciary before Thomas Jefferson took office. The commissions were signed by President Adams and sealed by acting Secretary of State John Marshall (who later became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and author of this opinion), but they were not delivered before the expiration of Adams’s term as president. Thomas Jefferson refused to honor the commissions, claiming that they were invalid because they had not been delivered by the end of Adams’s term. William Marbury (P) was an intended recipient of an appointment as justice of the peace. Marbury applied directly to the Supreme Court of the United States for a writ of mandamus to compel Jefferson’s Secretary of State, James Madison (D), to deliver the commissions. The Judiciary Act of 1789 had granted the Supreme Court original jurisdiction to issue writs of mandamus “…to any courts appointed, or persons holding office, under the authority of the United States.” Issues 1. Does Marbury have a right to the commission? 2. Does the law grant Marbury a remedy? 3. Does the Supreme Court have the authority to review acts of Congress and determine whether they are unconstitutional and therefore void? 4. Can Congress expand the scope of the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction beyond what is specified in Article III of the Constitution? 5. Does the Supreme Court have original jurisdiction to issue writs of mandamus? Holding and Rule (Marshall) 1. Yes. Marbury has a right to the commission. The order granting the commission takes effect when the Executive’s constitutional power of appointment has been exercised, and the power has been exercised when the last act required from the person possessing the power has been performed. The grant of the commission to Marbury became effective when signed by President Adams. 2. Yes. The law grants Marbury a remedy.The very essence of civil liberty certainly consists in the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws whenever he receives an injury. One of the first duties of government is to afford that protection. Where a specific duty is assigned by law, and individual rights depend upon the performance of that duty, the individual who considers himself injured has a right to resort to the law for a remedy. The President, by signing the commission, appointed Marbury a justice of the peace in the District of Columbia. The seal of the United States, affixed thereto by the Secretary of State, is conclusive testimony of the verity of the signature, and of the completion of the appointment. Having this legal right to the office, he has a consequent right to the commission, a refusal to deliver which is a plain violation of that right for which the laws of the country afford him a remedy. 3. Yes. The Supreme Court has the authority to review acts of Congress and determine whether they are unconstitutional and therefore void. It is emphatically the duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of necessity, expound and interpret the rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the Court must decide on the operation of each. If courts are to regard the Constitution, and the Constitution is superior to any ordinary act of the legislature, the Constitution, and not such ordinary act, must govern the case to which they both apply. 4. No. Congress cannot expand the scope of the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction beyond what is specified in Article III of the Constitution. The Constitution states that “the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction in all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state shall be a party. In all other cases, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction.” If it had been intended to leave it in the discretion of the Legislature to apportion the judicial power between the Supreme and inferior courts according to the will of that body, this section is mere surplusage and is entirely without meaning. If Congress remains at liberty to give this court appellate jurisdiction where the Constitution has declared their jurisdiction shall be original, and original jurisdiction where the Constitution has declared it shall be appellate, the distribution of jurisdiction made in the Constitution, is form without substance. 5. No. The Supreme Court does not have original jurisdiction to issue writs of mandamus. To enable this court then to issue a mandamus, it must be shown to be an exercise of appellate jurisdiction, or to be necessary to enable them to exercise appellate jurisdiction. It is the essential criterion of appellate jurisdiction that it revises and corrects the proceedings in a cause already instituted, and does not create that case. Although, therefore, a mandamus may be directed to courts, yet to issue such a writ to an officer for the delivery of a paper is, in effect, the same as to sustain an original action for that paper, and is therefore a matter of original jurisdiction. Disposition Application for writ of mandamus denied. Marbury doesn’t get the commission. http://www.lawnix.com/cases/marbury-madison.html Fletcher v. Peck – Case Brief Summary Summary of Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U.S. 87, 6 Cranch 87, 3 L. Ed. 162 (1810). Facts In 1795, nearly every member of the Georgia state legislature was bribed to permit the sale of 30 million acres of land at less than two cents per acre for a total of $500,000. Only one member of the legislature voted against the legislation. The land was known as the Yazoo lands and eventually became the states of Alabama and Mississippi. As a result of public outrage, most of the legislators lost the following election and the new legislature passed a statute in 1796 essentially nullifying the transactions. Those who had purchased the land refused to accept the return of their purchase price and much of the land was resold to bona fide purchasers at great profit. Robert Fletcher (P) purchased 15,000 acres from John Peck (D) in 1803 for $3,000. Peck, in spite of the 1796 statute, had placed a covenant in the deed that stated that the title to the land had not been constitutionally impaired by any subsequent act of the state of Georgia. Fletcher sued Peck to establish the constitutionality of the 1796 act; either the act was constitutional and the contract was void, or the act was unconstitutional and Fletcher had clear title to the land. Issue Is a law that negates all property rights established under an earlier law unconstitutional? Holding and Rule (Marshall) Yes. A law that negates all property rights established under an earlier law is unconstitutional for violating the Contract Clause (Article I, Section 10) of the United States Constitution. The court, while deploring the extensive corruption in the earlier state legislature, held that contracts signed under the original law must be accepted as valid. The motives of the legislators could not be considered by the Court and were not the responsibility of bona fide purchasers who were following the law. The court acknowledged that a legislature can repeal any act of a former legislature, but that this principle did not apply where the legislature sought to undo actions taken under the previous act while it was still valid. The court held that the land grant was a type of contract, and therefore the Contract Clause (Art. I, sec. 10 of the U.S. Constitution) applied. The Contract Clause states: “No State shall … pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.” The court held that the 1796 law was an unconstitutional ex post facto law that sought to penalize bona fide purchasers for wrongs committed by those from whom they were purchasing. Disposition Judgment for Peck. The 1796 statute was unconstitutional and the sale to Fletcher conveyed clear title. Concurrence (Johnson) While states may not abrogate contracts, they may pass legislation that affects contracts. McCulloch v. Maryland – Case Brief Summary Summary of McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316, 4 Wheat. 316, 4 L. Ed. 579 (1819). Facts Maryland (P) enacted a statute imposing a tax on all banks operating in Maryland not chartered by the state. The statute provided that all such banks were prohibited from issuing bank notes except upon stamped paper issued by the state. The statute set forth the fees to be paid for the paper and established penalties for violations. The Second Bank of the United States was established pursuant to an 1816 act of Congress. McCulloch (D), the cashier of the Baltimore branch of the Bank of the United States, issued bank notes without complying with the Maryland law. Maryland sued McCulloch for failing to pay the taxes due under the Maryland statute and McCulloch contested the constitutionality of that act. The state court found for Maryland and McCulloch appealed. Issues 1. Does Congress have the power under the Constitution to incorporate a bank, even though that power is not specifically enumerated within the Constitution? 2. Does the State of Maryland have the power to tax an institution created by Congress pursuant to its powers under the Constitution? Holding and Rule (Marshall) 1. Yes. Congress has power under the Constitution to incorporate a bank pursuant to the Necessary and Proper clause (Article I, section 8). 2. No. The State of Maryland does not have the power to tax an institution created by Congress pursuant to its powers under the Constitution. The Government of the Union, though limited in its powers, is supreme within its sphere of action, and its laws, when made in pursuance of the Constitution, form the supreme law of the land. There is nothing in the Constitution which excludes incidental or implied powers. If the end be legitimate, and within the scope of the Constitution, all the means which are appropriate and plainly adapted to that end, and which are not prohibited, may be employed to carry it into effect pursuant to the Necessary and Proper clause. The power of establishing a corporation is not a distinct sovereign power or end of Government, but only the means of carrying into effect other powers which are sovereign. It may be exercised whenever it becomes an appropriate means of exercising any of the powers granted to the federal government under the U.S. Constitution. If a certain means to carry into effect of any of the powers expressly given by the Constitution to the Government of the Union be an appropriate measure, not prohibited by the Constitution, the degree of its necessity is a question of legislative discretion, not of judicial cognizance. The Bank of the United States has a right to establish its branches within any state. The States have no power, by taxation or otherwise, to impede or in any manner control any of the constitutional means employed by the U.S. government to execute its powers under the Constitution. This principle does not extend to property taxes on the property of the Bank of the United States, nor to taxes on the proprietary interest which the citizens of that State may hold in this institution, in common with other property of the same description throughout the State. Disposition Reversed; judgment for McCulloch. Note This opinion is occasionally cited as Mccullough v. Maryland or alternatively as Maryland v. McCulloch. Gibbons v. Ogden – Case Brief Summary Summary of Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1, 9 Wheat. 1, 6 L. Ed. 23 (1824). Facts New York granted Robert R. Livingston and Robert Fulton the exclusive right of steam boat navigation on New York state waters. Livingston assigned to Ogden the right to navigate the waters between New York City and certain ports in New Jersey. Ogden (P) brought this lawsuit seeking an injunction to restrain Gibbons (D) from operating steam ships on New York waters in violation of his exclusive privilege. Ogden was granted the injunction and Gibbons appealed, asserting that his steamships were licensed under the Act of Congress entitled “An act for enrolling and licensing ships and vessels to be employed in the coasting trade and fisheries, and for regulating the same.” Gibbons asserted that the Act of Congress superseded the exclusive privilege granted by the state of New York. The Chancellor affirmed the injunction, holding that the New York law granting the exclusive privilege was not repugnant to the Constitution and laws of the United States, and that the grants were valid. Gibbons appealed and the decision was affirmed by the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and Correction of Errors, the highest Court of law and equity in the state of New York. The Supreme Court granted certiorari. Issues 1. May a state enact legislation that regulates a purely internal affair regarding trade or the police power, or is pursuant to a power to regulate interstate commerce concurrent with that of Congress, which confers a privilege inconsistent with federal law? 2. Do states have the power to regulate those phases of interstate commerce which, because of the need of national uniformity, demand that their regulation, be prescribed by a single authority? 3. Does a state have the power to grant an exclusive right to the use of state waterways inconsistent with federal law? Holding and Rule (Marshall) 1. No. A state may not legislation inconsistent with federal law which regulates a purely internal affair regarding trade or the police power, or is pursuant to a power to regulate interstate commerce concurrent with that of Congress. 2. No. States do not have the power to regulate those phases of interstate commerce which, because of the need of national uniformity, demand that their regulation, be prescribed by a single authority. 3. No. A state does not have the power to grant an exclusive right to the use of state navigable waters inconsistent with federal law. The laws of New York granting to Robert R. Livingston and Robert Fulton the exclusive right of navigating state waters with steamboats are in collision with the acts of Congress. The acts of Congress under the Constitution regulating the coasting trade are supreme. State laws must yield to that supremacy, even though enacted in pursuance of powers acknowledged to remain in the States. A license, such as that granted to Gibbons, pursuant to acts of Congress for regulating the coasting trade under the Commerce Clause of Article I confers a permission to carry on that trade. The power to regulate commerce extends to every type of commercial intercourse between the United States and foreign nations and among the States. The commerce power includes the regulation of navigation, including navigation exclusively for the transportation of passengers. It extends to vessels propelled by steam or fire as well as to wind and sails. The power to regulate commerce is general, and has no limitations other than those prescribed in the Constitution itself. It is exclusively vested in Congress and no part of it can be exercised by a State. While the commerce power does not stop at the external boundary of a State, it does not extend to commerce which is completely internal. State inspection laws, health laws, and laws for regulating transportation and the internal commerce of a State fall within the state police power and are not within the power granted to Congress. Disposition Reversed – judgment for Gibbons. COHENS v. VIRGINIA Location: Elizabeth River Parish (now site of Norfolk Naval Station) Facts of the Case An act of Congress authorized the operation of a lottery in the District of Columbia. The Cohen brothers proceeded to sell D.C. lottery tickets in the state of Virginia, violating state law. State authorities tried and convicted the Cohens, and then declared themselves to be the final arbiters of disputes between the states and the national government. Question Did the Supreme Court have the power under the Constitution to review the Virginia Supreme Court's ruling? Conclusion Split Vote In a unanimous decision, the Court held that the Supreme Court had jurisdiction to review state criminal proceedings. Chief Justice Marshall wrote that the Court was bound to hear all cases that involved constitutional questions, and that this jurisdiction was not dependent on the identity of the parties in the cases. Marshall argued that state laws and constitutions, when repugnant to the Constitution and federal laws, were "absolutely void." After establishing the Court's jurisdiction, Marshall declared the lottery ordinance a local matter and concluded that the Virginia court was correct to fine the Cohens brothers for violating Virginia law. http://www.oyez.org/cases/1792-1850/1821/1821_0 DARTMOUTH COLLEGE v. WOODWARD Location: Dartmouth College Facts of the Case In 1816, the New Hampshire legislature attempted to change Dartmouth College-- a privately funded institution--into a state university. The legislature changed the school's corporate charter by transferring the control of trustee appointments to the governor. In an attempt to regain authority over the resources of Dartmouth College, the old trustees filed suit against William H. Woodward, who sided with the new appointees. Question Did the New Hampshire legislature unconstitutionally interfere with Dartmouth College's rights under the Contract Clause? Conclusion Decision: 5 votes for Dartmouth College, 1 vote(s) against Legal provision: US Const. Art 1, Section 10 In a 6-to-1 decision, the Court held that the College's corporate charter qualified as a contract between private parties, with which the legislature could not interfere. The fact that the government had commissioned the charter did not transform the school into a civil institution. Chief Justice Marshall's opinion emphasized that the term "contract" referred to transactions involving individual property rights, not to "the political relations between the government and its citizens."