Douglas D. McFarland - Florida Coastal School of Law

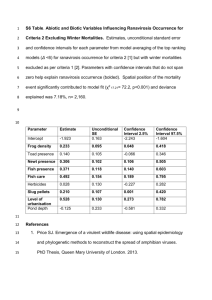

advertisement