Truly From Africa? The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah

advertisement

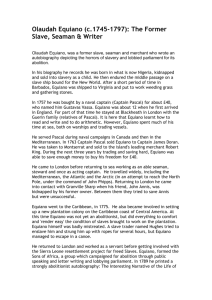

Evans 1 Truly From Africa? The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African has become one of the most memorable autobiographical tales of all time. It not only played a key role in the abolition of the British slave trade, it is also universally accepted as the fundamental text in the genre of the slave narrative. The most frequently quoted sections of The Interesting Narrative are the early chapters in which Equiano describes his life in Africa as well as his experience on the Middle Passage crossing the Atlantic to America. It is difficult to think of any historical account of the Middle passage that does not quote Equiano’s first-hand account of its horrors. However, this treasured autobiography has come under fire in recent years. It seems that some scholars believe Equiano may have invented his African childhood. Baptismal and naval records indicate that Equiano was really born in South Carolina around 1747. And yet Equiano states clearly in his autobiography that he was born in Africa “in a charming fruitful vale, named Essaka” (Equiano, 3). If the accounts are true and Equiano was really born in South Carolina, does it change the context of The Interesting Narrative and its importance? The first document, a baptismal record, contradicts Equiano’s claim to an African birth. It comes from St. Margaret’s Church in London. The parish register for the church reads on February 9, 1759: “Gustavus Vassa a black born in Carolina 12 years old” (Lovejoy, 323). Not only does this contradict the birth place of Equiano, but it also puts his age for enslavement and arrival in England at odds. The second document supporting the theory that Equiano invented his African childhood comes from the muster book of the Racehorse. While Gustavus Vassa is not listed, a Gustavus Weston is. The book identifies the man as a twenty eight-year-old seaman. Critics believe that Gustavus Weston is a misspelling and is really supposed to read Gustavus Evans 2 Vassa. We know through The Interesting Narrative that Equiano was on board the Racehorse, however, the muster has written that he was born in South Carolina. Speculation has led some scholars to believe that the details on the baptismal record were the good intentions of Equiano’s godparents, Mary Guerin and her brother Maynard who were cousins of Equiano’s owner Pascal. It is possible that the Guerins and Pascal wanted people to think that Equiano was Creole born because he had mastered English so well by the year of his baptismal and Creoles had a higher status in society than African slaves. After doubts had arisen in 1794 about Equiano’s birth place, he responded on the first page of the ninth addition of The Interesting Narrative, saying “…I should take notice thereof, and it is only needful of me to appeal to those numerous and respectable persons of character who knew me when I first arrived in England, and could speak no language but that of Africa” (Lovejoy, 335). Mary Guerin was willing to testify that Equiano was only fluent in the African language of Igbo, when she had met him, thus proving that he was indeed born in Africa. Equiano himself was responsible for the muster entries of the Racehorse. According to Paul Lovejoy, the reason for Equiano’s claim to a South Carolina birth could lie in the fact that “as a freeman and the assistant to the noted Dr. Irving that he [Equiano] thought that a Carolina birth was more respectable than an African birth at that point in his life” (Lovejoy, 336). At this time, Equiano was trying to achieve a degree of British respectability and may have felt that his African birth may cause a hindrance to that goal. Equiano’s identity crisis was certainly solved by the time The Interesting Narrative was published and he was suitably proud and public about his origins. Lovejoy again points out doubts about Equiano’s birth place being South Carolina, saying “Circumstantial evidence, specifically his [Equiano’s] association with Dr. Irving, who Evans 3 was to rely on Vassa’s knowledge of Igbo in the abortive Mosquito Shore scheme of 1776, raises questions of the reliability of what Vassa allowed to be entered in the muster books” (337). However, other critics still have doubts about Equiano’s African origins. For one thing, the timing of publication for The Interesting Narrative was no coincidence. The abolition of slavery had become a hot topic since the 1780s and its popularity grew after the founding of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in London (Carretta, 2). Due to the growing public interest in abolition, Parliament passed a law to regulate some of the conditions on overcrowded slave ships. In order to abolish the slave trade entirely, arguments were needed from Africans. Up until 1789, the only published black witnesses were clearly fictitious. This is where, according to biographer Vincent Carretta, Equiano assumed the role of an African. Carretta says that “the revelation that Gustavus Vassa was a native-born Igbo originally named Olaudah Equiano appears to have evolved during 1788 in response to the needs of the abolitionist movement” (Carretta, 3). Equiano had only intended to give a testimony to Parliament based on his experience in the West Indies. But after Parliament showed no interest in hearing his testimony about the West Indies, Equiano wrote a letter to the legislators: “if it should please Providence to enable me to return to my estate in Elese, in Africa, and to be happy enough to see any of these worthy senators there…we will have such a libation of pure virgin palm-wine, as shall make their hearts glad!!!” (Carretta, 4). This is the first generalized memory Equiano brings up of Africa and it is one that is not seen in his The Interesting Narrative. It seems that Equiano knew he had to invoke the memory of Africa to catch legislators’ attention. He also knew that legislators were looking for exactly the kind of detailed account of Africa and the trade that he would eventually provide in his autobiography. Evans 4 If Equiano’s account of Africa was created, rather than remembered, where would the author have gotten such detailed information about Africa? According to a researcher, Ogude, “Equiano’s narrative is to a large extent fictional, based on the popular eighteenth century literary form: the voyage” (39). It is possible that Equiano drew his impressions of Africa from widely published works on Africa. There were many published documents across Europe detailing tales and traditions that circulated among slaves and former slaves (Lovejoy, 332). Ogude goes on to say that “[Equiano’s] information was directly derived from the eighteenth century geography of Africa as was then conceived by European writers” (35). At a closer look, scholars have detected that whenever specific accounts can be verified in The Interesting Narrative, Equiano uses less detail. There are some instances in the book when Equiano mentions things about Africa but does not footnote them. For instance, the opening sentence in which Equiano describes Africa “that part of Africa, known by the name of Guinea, to which the trade for slaves is carried on, extends along the coast above 3400 miles” can be correlated to a passage from Benezet’s Some Historical Account of Guinea: “That part of Africa from which the Negroes are sold to be carried into slavery, commonly known by the name of Guinea, extends along the coast three or four thousand miles” (Carretta, 313). This just shows that when accounts are verified, they almost always tend to lead back to a European source. Perhaps Equiano’s honesty would not be questioned so veraciously if other misleads had not been found in his Narrative. The relationship between Dr. Irving and Equiano is depicted as being an important one to Equiano. And yet, Equiano claims in his book that Dr. Irving died from eating poisoned fish in Jamaica in late 1776 or early 1777. In truth, Dr. Irving was alive and well, living in Jamaica until his death in 1797. Scholars continue to be perplexed at how Equiano could provide such a mistaken fact considering the closeness of the two men. Even Evans 5 more puzzling is that Dr. Irving’s partner, Alexander Blair, subscribed to the first edition of The Interesting Narrative in 1789 and yet the detail of Dr. Irving’s “death” was never changed in later edition (Lovejoy, 327). It has been argued that, fabricated or not, Equiano’s autobiography served its purpose of ridding the British slave trade. In fact, many scholars agree that the fictitious nature of the first part of The Interesting Narrative demonstrates Equiano’s great writing talent. Carretta says of the opening of Equiano’s biography “It is easy to imagine why emotionally he may have needed to tell such a story. Enslavement, whether initially in Africa or South Carolina, had severed his African roots, effectively denying him a past outside of slavery” (8). The story of his childhood in Africa appealed to readers’ pathos and evoked a sense of sadness and empathy towards Equiano’s plight, causing an even stronger uprising against the slave trade. Unfortunately, we’ll never know the whole truth behind Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative. Scholars will be debating this subject for some time. As Vincent Carretta states in his biography “Anyone who still contends that Equiano’s account of the early years of his life is authentic is obligated to account for the powerful conflicting evidence” (2). But, Paul Lovejoy argues that “…evidence derived from culture and context confirms his [Equiano’s] African birth, …and the documents that claim otherwise have to be interpreted accordingly” (339). Whether Equiano was born in Africa or South Carolina, The Interesting Narrative succeeded in its goal: the abolition of the British slave trade. Without Equiano’s carefully crafted details about Africa and the Middle Passage, readers’ emotions would not have been evoked. Equiano sparked readers’ anger and rage when he depicted an innocent image of a child who was ripped away from everything he knew and loved. He shed a light on slavery that had never been turned on for Evans 6 white readers. It may be safe to say that The Interesting Life can no longer be viewed as a historical, non-fiction piece of work but it is still a very important piece of literature in history. Evans 7 Works Cited Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African. Biography of a Self-Made Man. New York: Penguin, 2005. Lovejoy, Paul. “Autobiography and Memory: Gustavus Vassa, alias Olaudah Equiano, the African.” Slavery and Abolition. 27.3 (2006): 317-347. Ogude, S.E. “Facts into Fiction: Equiano’s Narrative Reconsidered.” Research in African Literatures. 13.1 (1982): 31-43.