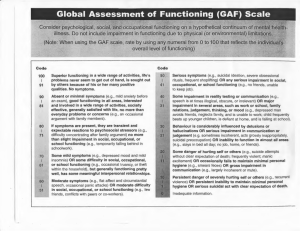

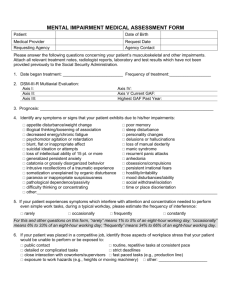

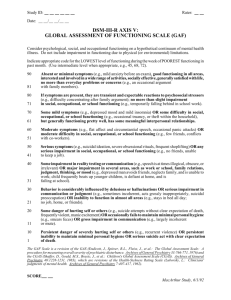

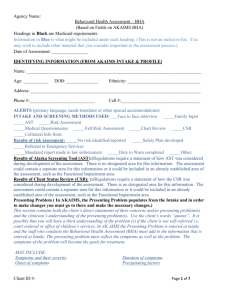

Reliability of the global assessment of functioning scale

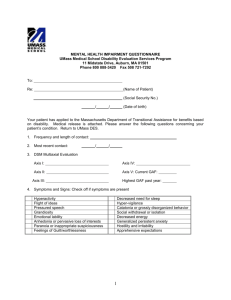

advertisement