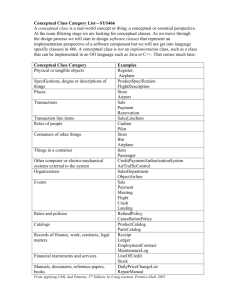

Conceptual Management Tools

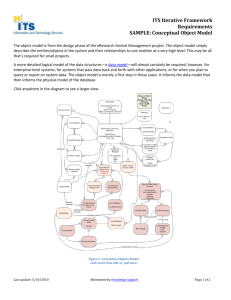

advertisement