2010 Folio Literary Magazine - Southern Connecticut State University

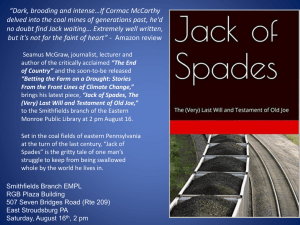

advertisement