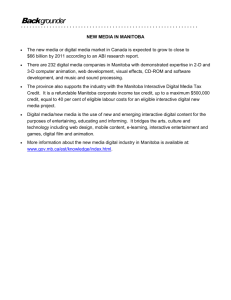

a healthy investment

advertisement