Communication Text 4th ed.

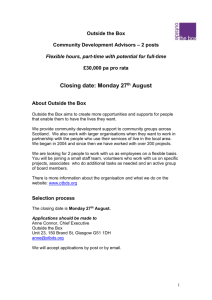

advertisement