Boris Pasternak and Shakespeare's Hamlet

advertisement

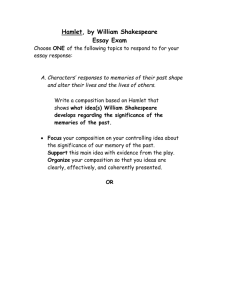

The Bard of Avon & the Church of Rome by Brendan D. King The Bard of Avon in Soviet Russia: Boris Pasternak and Shakespeare’s Hamlet Over the years I have translated several of Shakespeare’s plays: Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Antony and Cleopatra, King Henry IV (Parts I and II), King Lear, and Macbeth. The demand for simple and readable translations is great and seemingly inexhaustible. Every translator flatters himself with the hope that he, more than others, will succeed in meeting it. I have not escaped the common fate. Nor are my opinions on the aims and problems of translating literary works exceptional. I believe, as do many others, that closeness to the original is not ensured only by literal exactness or by similarity of form: the likeness, as in a portrait, cannot be achieved without a lively and natural method of expression. As much as the author, the translator must confine himself to a vocabulary which is natural to him and to avoid the literary artifice involved in stylization. Like the original text, the translation must create an impression of life and not of verbiage. —Boris Pasternak, “Translating Shakespeare” (1956)1 Outside of his homeland, Boris Pasternak is remembered, if at all, as the Nobel Prize winning author of Doctor Zhivago. In his native Russia, however, he is far better known as one of the greatest poets in the history of the Russian language. Furthermore, Pasternak’s Russian translations of the plays and sonnets of William Shakespeare are still considered the best ever produced. According to his biographer Lazar Fleishman, Pasternak’s fascination with the Bard of Avon dated back to the last days of the House of Romanov. It was only after the Bolshevik Revolution, however, that tight- 14 January/February 2014 StAR ening censorship of the arts forced Pasternak to make his living through translating verse. Pasternak’s earliest attempt to translate Shakespeare into Russian began in 1924, but was ultimately set aside.2 By the late 1930s, however, Pasternak’s subsequent experiences with translating English, German, and Georgian language poets had left him far better equipped to translate William Shakespeare. His second attempt would, like the first, center around the play, Hamlet, which the renowned Soviet theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold commissioned him to translate in January 1939. At the time, Meyerhold intended to stage Pasternak’s translation at Leningrad’s Pushkin Theater. Tragically, Joseph Stalin decided otherwise.3 On June 10, 1939, Vsevolod Meyerhold was arrested at his apartment by the Soviet secret police, or NKVD. After, “confessing” under torture to espionage and treason, the director was convicted on all charges and shot in January 1940. By this time, however, Pasternak had become personally involved in the project and had no intention of laying Hamlet aside.4 When his translation was finished, Pasternak discreetly read it aloud to a group of trusted friends, one of whom was the acclaimed actor Boris Livanov. Having long dreamed of playing Hamlet onstage, Livanov immediately shared Pasternak’s work with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, the sole surviving founder of the Moscow Art Theatre. Despite being in his eighties, Nemirovich-Danchenko informed his actors that Pasternak had opened his eyes to a new Shakespeare. He was even more charmed when he met the translator in person. As a result, Nemirovich-Danchenko announced that he would personally direct the production.5 Unfortunately, Stalin would again decide otherwise. At a banquet in the spring of 1941, Boris Livanov informed Stalin of the Moscow Art Theatre’s plans to stage Pasternak’s translation of Hamlet. Stalin not only showed no enthusiasm for the production but dismissed Shakespeare’s play as “decadent”. In consequence, the Moscow Art Theatre immediately suspended rehearsals.6 Nemirovich-Danchenko did not give up hope, however. He continued to list the production as forthcoming. It was only the German invasion which forced the Moscow Art Theatre to indefinitely shelve the project. Having contended for decades with both Tsarist and Soviet censors, Nemirovich-Danchenko knew that “poetry of doubt and skepticism” would never be allowed on the stages of a wartime police state. Although he hoped to restart rehearsals after the war turned against Germany, Vladimir NemirovichDanchenko died in April 1943. The Moscow Art Theatre was unable to proceed without him.7 Pasternak’s translation of Hamlet would not be staged until the spring of 1954, a year after Stalin’s death, when it debuted at Leningrad’s Pushkin Theatre. Although the performance realized one of Pasternak’s cherished dreams, he was then busy writing Doctor Zhivago and was unable to attend.8 Some may wonder why a Soviet-era poet would identify so deeply with the tale of Shakespeare’s Danish Prince. The answer lies within the very culture which the Communist police state sought to destroy. In Russia, it has long been customary for poets and writers to be seen as the nation’s conscience. This is the reason why the Soviet secret police subjected all writers to persecution, censorship, and frivolous arrest. Even militant Stalinists were terrified of nighttime knocks on their apartment doors. The independent minded Pasternak was no exception. According to Lazar Fleishman, Pasternak translated Hamlet under the full awareness that he would likely not live to finish it. Sir Laurence Olivier famously summarized Hamlet as “the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind”. To Pasternak, this interpretation was utterly preposterous. He later wrote: Absence of will power did not exist as a theme in Shakespeare’s time; it aroused no interest. Nor does Shakespeare’s portrait of Hamlet, drawn so clearly and in so much detail, suggest a neurotic. Hamlet is a prince of the blood who never, for a moment, ceases to be conscious of his rights as heir to the throne; he is the spoiled darling of an ancient court, and selfassured in the awareness of his natural gifts. The sum of the qualities with which he is endowed by Shakespeare leaves no room for flabbiness: it precludes it. Rather, the opposite is true: the audience, impressed by his brilliant prospects, is left to judge the greatness of his sacrifice in giving them up for a higher aim. From the moment of the Ghost’s appearance, Hamlet gives up his will in order to “do the will of Him that sent him”. Hamlet is not a drama of weakness, but of duty and self-denial. It is immaterial that, when appearance and reality are shown to To discover in the distant echoes What the coming years may hold in store. The nocturnal darkness with a thousand Binoculars is focused onto me. Take away this cup, O Abba Father, Everything is possible to Thee. I am fond of this Thy stubborn project, And to play my part I am content. But another drama is in progress, And, this once, O let me be exempt. Ophelia, John William Waterhouse, 1894. be at variance—to be indeed separated by an abyss—the message is conveyed by supernatural means and that the Ghost commands Hamlet to exact vengeance. What is important is that chance has allotted Hamlet the role of judge of his own time and servant of the future. Hamlet is the drama of a high destiny, of a life devoted and preordained to a heroic task.9 Boris Pasternak died in his sleep during the night of May 30–31, 1960.10 At his request, a Russian Orthodox funeral liturgy, or Panikhida, was secretly offered for the repose of his soul.11 Despite the best efforts of the KGB, almost two thousand mourners attended his civil funeral in the writer’s colony of Peredelkino.12 According to eyewitnesses, the Party officials stage-managing the funeral were horrified to hear the assembled mourners recite from memory a banned Pasternak poem which compared Shakespeare’s Hamlet to Soviet reality.13 In a translation by the poet’s sister Lydia Pasternak Slater, it reads as follows: The murmurs ebb; onto the stage I enter. I am trying, standing at the door, But the plan of action is determined, And the end irrevocably sealed. I am alone; all round me drowns in falsehood: Life is not a walk across a field.14 Brendan D. King is a freelance writer, translator, and researcher. In addition to the St. Austin Review, his articles have appeared in the Remnant, the Catholic Family News, and Angelus Magazine. He lives in St. Cloud, MN. References 1. Boris Pasternak, I Remember: Sketch for an Autobiography (Pantheon Books, 1959), p. 125. 2. Lazar Fleishman, Boris Pasternak: The Poet and his Politics (Harvard University Press, 1990), p. 136. 3. Ibid., pp. 218–19. 4. Ibid., pp. 219–20. 5. Ibid., pp. 221–22. 6. Ibid., p. 222. 7. Ibid., pp. 222–23. 8. Ibid., pp. 270–71. 9. Pasternak, pp. 130–31. 10. Fleishman, p. 312. 11. Olga Ivinskaya, A Captive of Time: My Years with Pasternak (Doubleday & Company, 1978), p. 332. 12. Ibid., pp. 324–29. 13. Ibid., pp. 330–32. 14. Pasternak: Fifty Poems, Chosen and Translated by Lydia Pasternak Slater (Barnes & Noble, 1963), p. 57. StAR January/February 2014 15