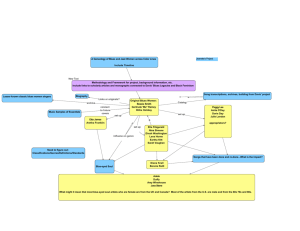

Gender references in rap lyrics

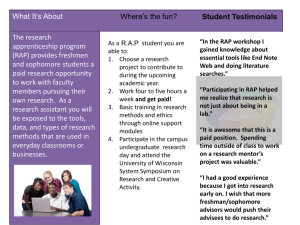

advertisement