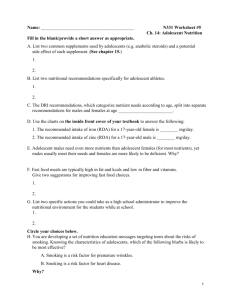

Reckless Behavior in Adolescence: A Developmental

advertisement