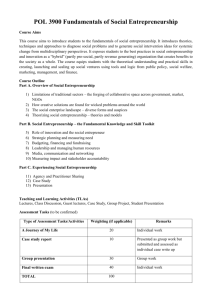

"Social" Business and Why Does the Answer Matter?

advertisement