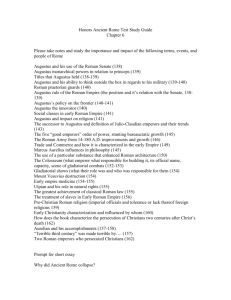

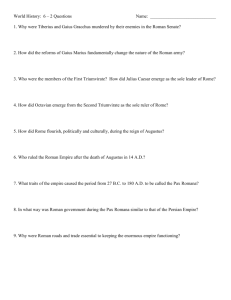

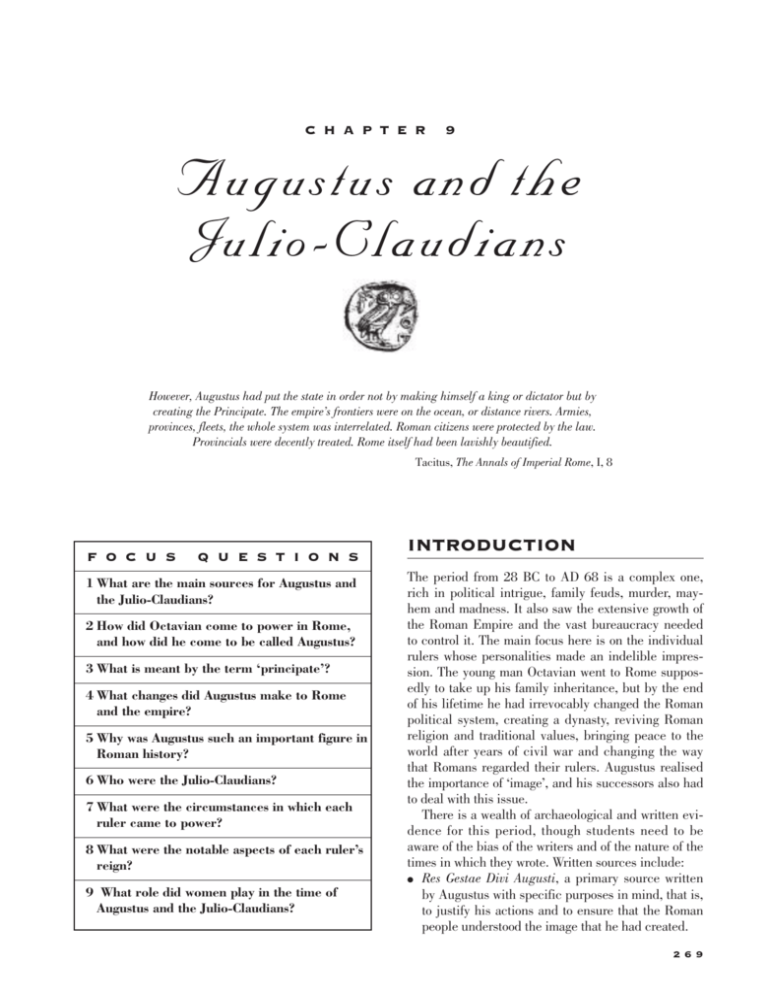

Augustus and the Julio-Claudians

advertisement