prescription drugs - Alliance for Health Reform

advertisement

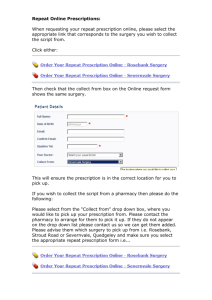

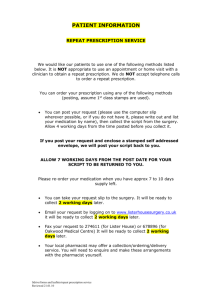

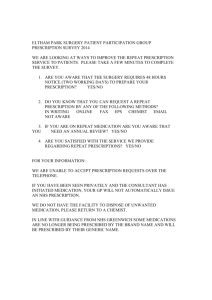

Pharmaceuticals are a central part of the American health care system. New medications are greatly improving health outcomes and the overall quality of life, and many are replacing or enhancing surgery and other invasive treatments. Others prevent chronic conditions from worsening and causing significant disability. During the last decade alone, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved more than 300 new prescription drugs. Among these are breakthrough treatments for life-threatening conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, cancer, cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia.1 6 CHAPTER 6 KEYFACTS In 2002, spending on prescription drugs reached $162.4 billion, or 10.5 percent of total health spending.a Prescription Drugs PRESCRIPTION DRUGS Between 1982 and 2002, drug prices rose at an average annual rate of 1.75 percentage points over the rate of medical inflation. Between 2002 and 2003, projected U.S. spending on drugs at the retail level rose by 13.4 percent, compared to a rise of 6.5 percent in hospital spending.b Between 40 and 60 percent of all employer costs for retirees 65 and older can be attributed to prescription drugs.c The Medicare legislation enacted in 2003 will help employers reduce their retiree drug costs by providing tax-free subsidies amounting to an estimated $71 billion over ten years.d Global spending on health care research and development (R&D), much of which is for pharmaceuticals and related science and technology, is estimated to exceed $100 billion in 2004.e The time it takes the Food and Drug Administration to review an application for a new drug has dropped from an average of 30 months in 1983 to 13 months in 2002.f Reforms made in 2003 to a 1984 pharmaceutical patent law popularly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act prohibit brand name drug manufacturers from filing additional subsidiary drug patents that are based on packaging, metabolites, and intermediate forms of a drug.g Thirty-nine states have established or authorized programs providing Yet prescription drugs are sometimes pharmaceutical assistance in the form of subsidized coverage or price controversial, mostly because of their discounts to seniors and individuals with disabilities.h (See chart, "State cost. In recent years, the growth rate in Pharmacy Assistance Programs.") retail prescription drug expenditures has outpaced that in almost all other health For key fact sources, see endnotes. care sectors. During the 1990s, spending on prescription drugs frequently registered double-digit annual cost growth rates — a trend that is expected to continue.2 Dramatic developments in prescription drug coverage are also occurring on the policy front. After years of debate, Congress narrowly passed the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (MMA), which President Bush signed into law in December 2003. In 2004, more than 7 million beneficiaries are expected to sign up for Medicare's new prescription drug discount card program, which includes annual subsidies of $600 for beneficiaries with annual incomes up to 135 percent of the federal poverty level (amounting to $12,372 for an individual in 2004). In 2006, millions more will enroll for coverage in the Medicare drug benefit program. (For an overview of the MMA, see Chapter 5, Medicare.) Other government health programs already have prescription drug coverage for their beneficiaries. These include Medicaid, various health programs administered by the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the health programs of the Office of Personnel Management, which manages health plans for civilian federal employees. Prescription drug coverage is also included in health plans offered to state government employees, union members ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM For updates, go to www.allhealth.org 51 Prescription Drugs CHAPTER 6 and millions of people working for private companies. The generosity of drug coverage varies substantially in state-administered Medicaid programs and among the plans that are offered to federal workers. Nowhere is the variation greater than in the private health insurance sector, where insurance companies are increasingly hiring pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to administer their drug plans. Employees may also hire PBMs directly. 6 A decade ago, PBMs focused primarily on filling prescriptions and distributing medications. In the process, they built sophisticated plants that could handle mail-order business as well as distribution through other channels, such as chain drug stores. Today PBMs not only distribute medications, they also decide with insurers and employers what the co-payments will be and what drugs will be included on the list of approved drugs, known as a formulary, and offered to health plan enrollees. PBMs also play a key role in negotiating the price of drugs. Among other tools, they obtain rebates or discounts on certain medications from drug manufacturers, which are typically shared between the PBM and the insurer or employer. According to a report prepared for the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, PBMs currently manage almost 80 percent of expenditures on prescription drugs in the U.S.3 PHARMACEUTICAL HOT BUTTON: COSTS A common theme runs through discussions of public and private drug coverage: steadily rising costs. According to IMS Health, a leading international consulting firm that monitors the drug industry, pharmaceutical spending was slated to rise by 11 percent in the U.S. and Canada in 2003, representing almost half of all global sales.4 Another U.S.-only estimate published in January 2004 projected that drug spending would rise by 13.4 percent in 2003, as compared to a 10.4 percent increase in spending for private insurance premiums, and a 6.5 percent rise in hospital spending.5 Between 1982 and 2002, drug spending grew faster than overall health spending, due to increased use and because pharmaceutical inflation exceeded medical 52 For updates, go to www.allhealth.org SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 inflation by an average annual rate of 1.75 percentage points.6 As a result, total drug spending more than tripled between 1990 and 2001.7 By 2002, expenditures had reached $162.4 billion, or 10.5 percent of total health spending. The forecast by leading economists is that pharmaceutical spending will reach 14.5 percent of health care spending by 2012 — before growth from the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) is taken into account.8 A number of factors have contributed to this growth. One is the aging of the population. Those age 65 and older filled almost four times as many prescriptions in 2000 as those under 65 (25.5 vs. 7.1).9 Other reasons include expanded use of maintenance drugs, rising sales of costlier drugs approved by the FDA during the 1990's, and stepped-up marketing efforts that include direct-to-consumer advertising. Some critics point to pharmaceutical companies' efforts to extend patent protection for their drugs, and thus exclusive marketing rights, by patenting drugs that provide little clinical improvement over other available drugs — so-called "me-too" drugs.10 In addition, consumers in managed care plans have, until fairly recently, had access to prescription drugs at low costs. Plans have tried to control drug costs by introducing tiered pricing arrangements, under which enrollees are charged more for drugs that are not designated by their health plan as preferred. The role of direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising in driving drug sales has been the subject of much debate. A recent study concluded that DTC advertising accounted for 12 percent, or $2.6 billion, of total growth in drug spending during 2000.11 For consumers who have insurance, the impact of years of steadily rising drug costs is now becoming evident in the form of increased copayments imposed by employers and insurers. Formularies (lists of health plans' approved drugs) have become more restrictive, and are generally accompanied by multi-tiered pricing arrangements, described above. For many consumers without health insurance, nondiscounted prices for drugs are often simply unaffordable. Looking ahead, pharmaceutical spending is expected to ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 CHAPTER 6 60 Number of NMEs 25 40 20 30 15 20 10 10 5 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 # OF NMEs (new molecular entities) 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Billions of dollars 30 50 0 Prescription Drugs U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT TRENDS, 1993 - 2003 35 6 0 TOTAL RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT SPENDING Note: Line relates to the right-hand Y-axis and models worldwide research and development (R&D) spending by PhRMA member companies. Source: U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (1997 & 2002). “Report to the Nation.” Number of NMEs represent sum of Standard and Priority Approvals. (http://www.fda.gov/cder/reports/rptntn97.pdf; http://www.fda.gov/cder/reports/rtn/2002/Rtn2002.PDF). Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (2004). “Pharmaceutical Industry Profile 2004.” (http://www.phrma.org/publications/publications//2004-03-31.937.pdf) consistently outstrip the growth in gross domestic product. Such projections worry many private companies, which are concerned about maintaining prescription drug coverage for current workers and retirees. Surveys have found that 40 to 60 percent of employer costs for retirees 65 and older are attributable to prescription drugs. 12 In response, the new Medicare law includes a provision intended to subsidize prescription costs for those employers that offer their retirees health plans with drug coverage — if that coverage is at least as generous as what Medicare will provide. Specifically, the law provides for direct tax-free subsidies set at 28 percent of a retiree's drug costs, not counting the initial $250 deductible, up to $5,000 annually.13 This means the dollar amount that corresponds to the 28 percent in drug spending will not be counted as income for the retiree, and will be fully tax-deductible to the employer. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that employer subsidies from 2004-2013 would cost the federal budget $71 billion.14 Already, 18 leading U.S. ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM companies have reported projected savings totaling $11.8 billion in retiree benefit costs in their 2003 financial reports.15 Large employers report that in the near future, they expect to begin using more stringent cost containment strategies to control drug costs for their retirees and for their younger workers. These strategies include requirements for providers to obtain prior authorization before prescribing certain medications and to use "therapeutic interchange" (drug substitution) programs that explicitly factor pharmaceutical costs into medical decision-making. Only about 1 percent of large companies offered their retirees discount drug cards in 2003,16 even though pharmacy-sponsored discount cards and cards sponsored by pharmaceutical companies are becoming more common. In the future, the role of Medicare supplemental insurance in the pharmaceutical market will diminish. The Medicare Modernization Act prohibits insurers from selling new Medigap policies with prescription drug coverage to beneficiaries For updates, go to www.allhealth.org 53 Prescription Drugs CHAPTER 6 enrolled in the new Part D program that starts in January 2006.17 In 2001, 7 percent of beneficiaries were enrolled in Medigap drug plans.18 PHARMACEUTICAL R&D AND RECENT CHANGES IN PATENT LAW 6 The research and development of new drugs — which can receive 20 years or more of patent protection — is a top priority for the pharmaceutical industry. During 2002-2003, the FDA approved 38 new drugs, or new molecular entities (NMEs).19 The agency's average review time has dropped substantially, from an average of 30 months in 1983, to 13 months in 2002.20 Global health care R&D spending, much of which is for pharmaceuticals and related science and technology, is estimated to exceed $100 billion in 2004.21 Looking ahead, many experts believe pharmaceutical R&D spending will remain strong, fueled by major advances in basic science and genomics that have created expanded research opportunities for drug discovery. (See chart, "U.S. Pharmaceutical R&D Trends, 1993-2002.") Profits remain high, with the U.S. pharmaceutical industry consistently ranked as the most profitable industry.22 The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 is one of the cornerstones of federal law affecting patent protections for pharmaceutical products. The statute attempts to balance the interests of brand name pharmaceutical manufacturers seeking patent protection, and the interests of generic companies that bring lower-cost products to the market once that protection expires. Major provisions of Hatch-Waxman include: a requirement for public disclosure of information on the patents for brand-name drugs; a process for compensating brand-name patent holders for substantial delays in FDA approval; a provision allowing the FDA to assign exclusive marketing rights to a generic firm for up to six months; legal protections that enable generic companies to conduct research on potential products during the life of the patent; and standardized mechanisms for bringing patent challenges in court.23 While the 1984 law did much to clarify rules for drug patent holders and generic companies, continuing litigation and antitrust complaints filed with the Federal Trade Commission recently prompted Congress and the 54 For updates, go to www.allhealth.org SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 FDA to undertake additional reforms. The net effect of the regulatory and statutory changes made in 2003 is that brand name companies can no longer file so-called subsidiary patents that are based on packaging, metabolites, and intermediate forms of a drug. In addition, FDA now has the authority to reassign marketing exclusivity if a generic company fails to begin marketing within a certain time period, or does not receive FDA approval for its product.24 STATES AIM TO EXPAND ACCESS, MODERATE DRUG SPENDING, PERHAPS TRY REIMPORTATION The recently enacted Medicare law will shape state decisions on prescription drug coverage over the next decade. Although CBO projects that federal Medicaid spending will drop by $142 billion over the 10-year period from 2004-2013, as Medicare picks up the tab, states will continue to feel fiscal pressure from prescription drug spending for Medicaid beneficiaries, and for individuals dually entitled to Medicare and Medicaid (dual eligibles). The drop in federal Medicaid spending is projected to occur primarily because prescription drug coverage for dual eligibles will shift from Medicaid to Medicare. But states will continue spending almost as much on Medicaid as they would have before the new law. This is because the federal government will require states to offset most of the additional Medicare drug costs the federal government will assume for dual eligibles. This provision in the new Medicare law, called the "clawback," is more fully described in Chapter 7, Medicaid, where there is also more information on how Medicaid's financing system works. Currently, states are using a variety of strategies to try to moderate growth in Medicaid drug costs, including the use of preferred drug lists or formularies, substitution of generic drugs for brand-name products, increases in deductibles and copays, imposition of prior authorization requirements for providers, development of drug utilization review programs, and negotiation of supplemental rebates with drug manufacturers.25 States are likely to use these and other cost-containment mechanisms in the future, as they seek to reduce drug costs from state employee health plans and various state-run drug assistance programs. ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 CHAPTER 6 Prescription Drugs STATE PHARMACY ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS AK NH VT WA MT ND ID MA NY WI* SD CA PA IA NE UT IL* CO RI CT MI WY NV ME MN OR KS 6 IN* MO OH WV VA KY NJ DE MD* DC NC TN AZ OK NM SC* AR MS TX AL GA LA HI FL* States with enacted pharmacy assistance programs (eligibility varies; may include disabled, others) States with enacted pharmacy assistance programs but currently not operational * FL, IL, IN, MD, SC, WI include approved “Pharmacy Plus” waivers Note: Data as of August 16, 2004. Source: National Conference of State Legislatures (2004). “State Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs.” August 16. (www.ncsl.org/programs/health/drugaid.htm) Retrieved September 7, 2004. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), as of April 2004, 39 states had established or authorized programs providing pharmaceutical coverage or discounts to seniors and individuals with disabilities. Thirty-one of those programs provide participants with direct subsidies using state funds, and some among this group also sponsor discount programs. Other states operate only discount programs.26 Much of the legislation creating subsidy programs is fairly recent, and implementation may be slowed by the need to develop ways to coordinate the state's coverage with Medicare-approved prescription drug discount cards, and then the Medicare Part D benefit. (See chart, "State Pharmacy Assistance Programs.") Currently, state pharmacy assistance programs vary significantly in the number of people served and in their ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM design. Many states have small programs. Two of the largest programs are operated by New Jersey and Pennsylvania. New Jersey's Pharmaceutical Assistance for the Aged and Disabled (PADD) program is older, established in 1975. In 2004, PADD will serve 227,500 seniors with incomes under $19,739. A second program, the Senior Gold Prescription Discount Program established in 2001, serves seniors with incomes up to $29,739. In Pennsylvania, the state recently authorized expansion of assistance to seniors with higher incomes. The state's original 1984 program serves individuals with incomes up to $14,500; legislation enacted in 2003 will provide subsidies to seniors enrolled in its newer program, PACENET, with incomes up to $23,500.27 Another strategy is being employed by six states — Florida, Indiana, Illinois, Maryland, South Carolina and Wisconsin — which have received approval for Section For updates, go to www.allhealth.org 55 Prescription Drugs CHAPTER 6 SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 most often known as reimportation. In its simplest form, it describes what a growing number of individuals have been doing for several years. Typically, they travel to Canada or 13% Mexico where it is possible Industry ($45.9 Billion) to buy prescription drugs — 6% including many that were NIH ($20.3 Billion) 70.5 manufactured in the United 62.1 States — at significantly 55.4 56% Other Federal ($5 Billion) lower prices. The practice of 25% 90.7 importation by entities other 81.7 74.7 Other ($10.4 Billion) * than drug manufacturers 77.2 violates federal law. But it has been, for the most part, tolerated by Food and Drug Administration authorities Total estimated U.S. health research expenditures, 2001 = $81.7 Billion under a "compassionate use" * ‘Other’ includes universities’ own funds, private foundations, voluntary health associations, and enforcement policy — if the private research institutes’ own funds. Research spending figures include, but are not limited to, drugs are imported by pharmaceutical research. Source: Research!America (2002) (www.researchamerica.org/publications/2001healthdollar.pdf) individuals for their own use and the quantities involved are small. The FDA has 1115 federal waiver programs known as Pharmacy Plus. indicated it will move aggressively to enforce the These programs provide drug assistance through federal prohibition on reimportation for commercial Medicaid to individuals with incomes between 100 use. But states such as Illinois, Minnesota, Wisconsin, percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty level.28 and New Hampshire are pushing FDA and Congress to rescind the prohibition and establish a system to allow Other states, including Maine, Vermont and Hawaii, registered wholesalers and distributors to make lowerhave sought to extend assistance to low-income priced drugs obtained from certain countries available individuals through waiver programs that establish in the U.S. discount programs based on Medicaid's "best" price, but court rulings have placed these programs in limbo.29 Moreover, some state and local governments are encouraging their employees to consider filling their Interest is also growing in the development of collective prescriptions through Canadian sources. For example, buying pools for prescription drugs. Following in February 2004, the Internet site for the State of extensive negotiations, in April 2004, the Department Wisconsin began listing prescription medicine prices of Health and Human Services (HHS) approved the first from three Canadian online pharmacists, along with multi-state purchasing pool for prescription drugs. order forms. The service is nearly identical to one Michigan, Vermont, New Hampshire, Alaska and posted a month earlier by Minnesota. Illinois' proposed Nevada are the five states in this pool. In 2004, program has been expanded to include countries in the Michigan expects to save $8 million in Medicaid costs, European Union. Similar initiatives have appeared in and Vermont is projecting savings of about $1 million, Westchester County, N.Y., and Springfield, Mass., while Nevada projects savings of $1.9 million, Alaska among others, for either municipal employees or the 30 $1 million, and New Hampshire $250,000. public.31 However, these Internet sites generally do not feature quotes for estimated savings that consumers can The newest and most controversial idea that is being expect to receive by purchasing their drugs from sites supported by some states to hold down drug costs is outside the U.S. SOURCES OF FUNDING FOR UNITED STATES HEALTH RESEARCH, 2001 6 56 For updates, go to www.allhealth.org ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 The Bush Administration announced in February 2004 that it was launching a study of how prescription drugs might be safely imported from Canada, which is scheduled to be released by December 2004. The study was required by the new Medicare drug law.34 (For more information on the law, see Chapter 5, Medicare.) Safety concerns about reimportation focus principally on the risk that counterfeit and adulterated pharmaceutical products not approved by FDA could find their way into the U.S. market. There is also debate about how much the American health care system would save in drug costs if reimportation were legalized. The Congressional Budget Office believes that such savings would be minimal.35 CURRENT POLICY DEBATES AND PROPOSALS The 2004 presidential election is focusing some attention on prescription drug coverage for Medicare beneficiaries and affordable medications for all consumers. The Bush administration argues that the Medicare law should be given a chance to work, since it makes the case that the new prescription drug benefit is the greatest advance in the Medicare program since it was enacted in 1965. On the other hand, the Kerry campaign maintains that the new benefit provides insufficient protection against rising pharmaceutical prices for seniors and for taxpayers who fund the program. The Kerry campaign lays out a six-point plan to reduce drug costs, including allowing "reimportation of safe, FDA-approved prescription drugs" from Canada.36 Calls to amend the current federal position on reimportation have become familiar in Washington. For example, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee has proposed legislation that would disallow a portion of the pharmaceutical industry's valuable R&D tax credit — as well as the normal business deduction for marketing, a category that includes directto-consumer ads — for companies found to be blocking ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM reimportation.37 (See chart, "Sources of Funding for U.S. Health Research, 2001.") A series of Senate and House hearings on safety issues associated with reimportation from Canada and the European Union have been held during the 108th Congress. AARP — which campaigned in support of the Medicare prescription drug law — is broadly supportive of reimportation. FDA, however, is deeply skeptical, and has pledged to vigorously oppose reimportation in a lawsuit that was filed in August 2004 by Vermont, which claims that the Medicare law requires the agency to issue reimportation regulations. The pharmaceutical industry also remains firmly opposed to reimportation. 6 Prescription Drugs One recent survey found that the share of U.S. residents saying they have bought prescription drugs from Canada or another country — by going there, by mail or on the Internet — rose from 5 percent in 2002 to 7 percent in 2003.32 IMS Health estimates that U.S. residents reimported $1.1 billion (in U.S. dollars) in drugs from Canada in 2003.33 CHAPTER 6 STORY IDEAS Medicare Rx discount cards: How clear and useful is CMS' web-based information on which cards in your area offer the best deals for seniors? Are price quotes correct in your local area? How much of a discount are seniors in your area getting using a Medicare-approved discount card? On which drugs? What prices are the discounts based on? How frequently do the prices and discounts change? Which cards are most popular? What is the sign-up rate for cards among seniors in your area? How many are receiving a $600 subsidy? Are there seniors who are dissatisfied with their Medicare discount cards, and if so, what have they done about it? Are there discount cards not sponsored by Medicare that offer better prices? Reimportation: What do state and local government officials believe consumers need to know about purchasing drugs reimported from abroad? What do physicians in your area think of reimporting prescription drugs? What are the relative advantages and disadvantages of reimporting drugs from Canada only, as compared to the European Union and other industrialized nations? How does reimportation affect the prices and safety of consumer products other than pharmaceuticals? State collective buying pools: Are there any drug purchasing pools in your state or region? How do they work? Have drug prices declined, remained flat, or risen as a result? State prescription drug assistance programs: Is there such a program in your state, and if so, how many For updates, go to www.allhealth.org 57 Prescription Drugs CHAPTER 6 individuals are enrolled, how is the program financed, and what benefits are available? Is the state program changing as a result of the Medicare prescription drug discount program? How is the state program likely to change when Medicare's drug benefit takes effect in 2006? 6 Drug detailers: Pharmaceutical companies send representatives into physician offices to explain the merits of their products, especially new products. Have either health plans or your state Medicaid program tried to send "counter-detailers" to physician offices, i.e., people who can explain the merits of less expensive drugs or alternative therapies? SOURCES AND WEBSITES Analysts/Advocates Stuart Altman, Sol C. Chaikin Professor of National Health Policy, Brandeis University Institute for Health Policy, 781/736-3803 Joseph Antos, Wilson H. Taylor Scholar in Health Care and Retirement Policy, American Enterprise Institute, 202/862-5938 CANDIDATES' VIEWS Senator Kerry has said that he favors changing the new Medicare law, so that the secretary of Health and Human Services would be required to negotiate drug discounts for Medicare beneficiaries, as the Department of Veterans Affairs does now for veterans. He offers several other proposals to lower drug costs, including making it easier for generic drugs to come to market.38 The Bush administration believes that new pharmaceutical coverage for seniors through Medicare and drug discount cards, sponsored by government and private entities, are the best vehicles for providing relief from prescription drug cost pressures for Medicare beneficiaries. The president couples this proposal with initiatives to expand private coverage (including drug coverage) using tax credits, high-deductible health plans paired with savings accounts, and new pooling arrangements for small businesses.39 The Bush administration has opposed reimportation, arguing it is potentially both unsafe and unlikely to result in substantial savings to the U.S. health system. However, President Bush was showing more openness to the idea in late summer 2004. Senator Kerry supports drug reimportation. Robert Berenson, Senior Fellow, The Urban Institute , 202/833-7200 Aidan Hollis, Associate Professor, University of Calgary, 403/220-5861 Linda Bilheimer, Senior Program Officer, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 609/627-7530 Julie James, Principal, Health Policy Alternatives, 202/737-3390 Barbara Cooper, Director for the Commonwealth Fund Program on Medicare Future, The Commonwealth Fund, 212/606-3800 Chris Jennings, President, Jennings Policy Strategies, 202/879-9344 Karen Davis, President, Commonwealth Fund, 212/6063800 Joseph DiMasi, Director of Economic Analysis, Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, 617/636-2116 58 SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 Marilyn Moon, Vice-President and Health Program Director, American Institutes for Research, 301/592-2101 Patricia Neuman, Vice-President and Director of Medicare Policy Project, Kaiser Family Foundation, 202/347-5270 Judy Feder, Dean, Georgetown Univ. Health Policy Institute, 202/687-0880 Frank Palumbo, Professor and Director of the University of Maryland's Center on Drugs and Public Policy, University of Maryland, 410/706-2303 Beth Fuchs, Principal, Health Policy Alternatives, 202/707-7367 Enzo Pastore, Health Policy Director, Center for Policy Alternatives, 202/387-6030 Henry Grabowski, Professor of Economics, Duke University, 919/660-1839 Ron Pollack, Executive Director, Families USA, 202/6283030 Robert Helms, Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute, 202/862-5877 Uwe Reinhardt, Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Princeton University, 609/258-4781 David Herman, Executive Director, Seniors Coalition, 800/325-9891 John Rother, Director of Policy and Strategy, AARP, 202/434-3701 For updates, go to www.allhealth.org ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 Bruce Stuart, Executive Director, Peter Lamy Center for Drug Therapy and Aging, School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, 410/706-2434 John M. Vernon, Professor of Microeconomic Principles, Duke University, 919/660-1829 Bruce Vladeck, Professor of Health Policy and Geriatrics, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, 212/241-3845 Stanley Wallack, Executive Director of the Schneider Institute for Health Policy, Brandeis University, 781/7363901 Gail Wilensky, Senior Fellow, Project HOPE, 301/6567401 Dale Yamamoto, Health Actuarial Practice Leader, Hewitt Associates, 847/295-5000 Government and Related Groups Alan Holmer, President and CEO, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, 202/835-3420 Karen Ignagni, President and CEO, American's Health Insurance Plans, 202/778-3203 Kathleen Jaeger, President and CEO, Generic Pharmaceutical Association, 703/647-2390 Steve Jennings, Principal, Express Scripts, 202/216-2265 Mary Nell Lehnhard, Senior Vice President, Blue Cross/Blue Shield Association, 202/626-4781 Ed Mihalski, Director of Federal Affairs Public Policy Planning and Development, Eli Lilly, 202/434-1020 Janet Newport, Corporate Vice President of Regulatory Affairs, PacifiCare Health Systems, 714/825-5052 Jeff Sanders, Senior Vice President, Advance PCS, 480/319-4287 Leonard Schaeffer, Chairman of the Board of Directors and Chief Executive Officer, Wellpoint Health Networks, 805/557-6000 Lynn Bosco, Director, Center for Outcomes and Effectiveness Research/AHRQ, 301/427-1490 Ian Spatz, Executive Director Federal Public Policy, Merck and Co., 202/638-4170 Laura Dummitt, Director Health Care - Medicare Payment Issues, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 202/5127119 Kate Sullivan, Director of Health Policy, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 202/463-5734 Ann Marie Lynch, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, DHHS, 202/690-6870 Sally Walsh, Vice President of Federal Government Relations, Taxes, and Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, 202/715-1000 Deborah Platt Majoras, Chairman, Federal Trade Commission, 202/326-2180 Richard Price, Section Head for Healthcare and Medicine, Congressional Research Service, 202/707-7370 Daniel E. Troy, Chief Counsel, Food and Drug Administration, 301/827-1137 Stakeholders Ken Bowler, Vice President for Federal Relations, Pfizer, 202/783-7070 Phillip Burgess, National Director of Pharmacy Affairs, Walgreens, 847/914-3241 John Coster, Vice President of Federal and State Programs, National Association of Chain Drugstores, 703/549-3001 6 Prescription Drugs Stephen Schondelmeyer, Director and Department Head of Pharmacology Care & Health Systems, PRIME Institute, University of Minnesota, 612/624-9931 CHAPTER 6 Susan Winckler, Staff Counsel and Vice President for Policy and Communications, American Pharmacists Association, 202/628-4410 Websites AARP www.aarp.org Alliance for Health Reform www.allhealth.org American Enterprise Institute www.aei.org American Institutes for Research www.air.org Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services www.medicare.gov Diana Dennett, Executive Vice President, America's Health Insurance Plans, 202/778-3259 The Commonwealth Fund www.cmwf.org Robert Freeman, Executive Director of Public Policy, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, 302/886-4489 Congressional Budget Office www.cbo.gov Dan Haron, Vice President of Pharmacy Operations, Brooks Pharmacy, 401/825-3900 ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM For updates, go to www.allhealth.org 59 Prescription Drugs CHAPTER 6 6 SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 Energy and Commerce Committee, U.S. House http://energycommerce.house.gov Medicare Payment Advisory Commission www.medpac.gov Families USA www.familiesusa.org National Association of Chain Drug Stores www.nacds.org Federal Trade Commission www.ftc.gov National Institute for Health Care Management www.nihcm.org Finance Committee, U.S. Senate http://finance.senate.gov Pharmaceutical Care Management Association www.pcmanet.org Food and Drug Administration www.fda.gov The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) www.phrma.org The Generic Pharmaceutical Association www.gphaonline.org Health Affairs www.healthaffairs.org Hewitt Associates http://was4.hewitt.com/hewitt The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation www.rwjf.org Ways and Means Committee, U.S House http://waysandmeans.house.gov The Kaiser Family Foundation www.kff.org ENDNOTES 60 a Smith, Cynthia (2004). "Retail Prescription Drug Spending in the National Health Accounts." Health Affairs, January/February, p. 162. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved May 13, 2004. b Heffler, Stephen et al. (2004). "Health Spending Projections through 2013." Health Affairs, February 11, p. W4-81, W4-83. (http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/hlthaff.w4.79v1/DC1). Retrieved May 13, 2004. c McArdle, Frank et al. (2000). "The Implications of Medicare Prescription Drug Proposals for Employers and Retirees." Hewitt Associates LLC, July, p. 15. d Holtz-Eakin, Douglas (2004). "Estimating the Cost of the Medicare Modernization Act." Congressional Budget Office, testimony of CBO Director before the House Ways & Means Committee, March 24. (http://www.cbo.gov/showdoc.cfm?index=5252&sequence=0). Retrieved May 10, 2004. e Cockburn, Iain M. (2004). "The Changing Structure of the Pharmaceutical Industry." Health Affairs, 23(1), p. 12. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved May 18, 2004. f Carpenter, Daniel P. (2004). "The Political Economy of FDA Drug Review: Processing, Politics, and Lessons For Policy." Health Affairs, 23(1), p. 58, 59. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved May 18, 2004. g Schacht, Wendy H. & John R. Thomas. (2004). "The Hatch-Waxman Act: Legislative Changes Affecting Pharmaceutical Patents." Congressional Research Service, February 19, p. 6, 7. h National Conference of State Legislatures (2004). "State Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs." April 20. (www.ncsl.org/programs/health/drugaid.htm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 1 Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (2004). "The Value of Medicines: Longer and Better Lives, Lower Health Care Spending, A Stronger Economy." April 24. (http://www.phrma.org/publications/policy/24.04.2004.983.cfm). Retrieved May 13, 2004. 2 Smith, Cynthia (2004). "Retail Prescription Drug Spending in the National Health Accounts." Health Affairs, January/February, p. 162. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved May 13, 2004. For updates, go to www.allhealth.org ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 CHAPTER 6 Health Policy Alternatives Inc. (2003). "Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs): Tools for Managing Drug Benefit Costs, Quality, and Safety." August, p.5, 9. (http://www.pcmanet.org/2004_pdf_downloads/HPA_Study_Final.pdf). Retrieved May 13, 2004. 4 IMS Health (2004). "IMS Reports 9 Percent Constant Dollar Growth in '03 Global Pharma Sales." IMS Insights, March 15. (http://www.imshealth.com/ims/portal/front/articleC/0,2777,6599_3665_45365325,00.html). Retrieved May 13, 2004. 5 Heffler, Stephen et al. (2004). "Health Spending Projections Through 2013." Health Affairs, February 11, p. W4-81, W4-83. (http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/hlthaff.w4.79v1/DC1). Retrieved May 13, 2004. 6 Smith, Cynthia (2004). "Retail Prescription Drug Spending in the National Health Accounts." Health Affairs, January/February, p. 162. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved May 13, 2004. 7 The Kaiser Family Foundation (2003). "Impact of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising on Prescription Drug Spending." June, p. 2. (http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/6084-index.cfm). Retrieved May 13, 2004. 8 Smith, Cynthia (2004). "Retail Prescription Drug Spending in the National Health Accounts." Health Affairs, January/February, p. 166. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved May 13, 2004. 9 Thomas, Cindy Parks, Grant Ritter, & Stanley S. Wallack (2001). "Growth in Prescription Drug Spending Among Insured Elders." Health Affairs, Sept./Oct. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved July 30, 2004. 10 National Institute for Health Care Management (2002). "Changing Patterns of Pharmaceutical Innovation." May, p.3. (http://www.nihcm.org/innovations.pdf ). Retrieved August 24, 2004. 11 The Kaiser Family Foundation (2003). "Impact of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising on Prescription Drug Spending." June, p. 2. (http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/6084-index.cfm). Retrieved May 13, 2004. 12 McArdle, Frank et al. (2000). "The Implications of Medicare Prescription Drug Proposals for Employers and Retirees." Hewitt Associates LLC, July, p. 15. (http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/13415_1.pdf). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 13 O'Sullivan et al. (2003). "Overview of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003." Congressional Research Service, December 9, p. 11. 14 Holtz-Eakin, Douglas (2004). "Estimating the Cost of the Medicare Modernization Act." Congressional Budget Office, testimony of CBO Director before the House Ways & Means Committee, March 24. (http://www.cbo.gov/showdoc.cfm?index=5252&sequence=0). Retrieved May 10, 2004. 15 Wei, Lingling (2004). "Companies Expect Cost Savings From Medicare Act." Wall Street Journal, March 22. 16 McArdle, Frank, Kerry Kirkland, Dale Yamamoto, Michelle Kitchman, & Tricia Neuman (2004). "Retiree Health Benefits Now and in the Future: Findings from the Kaiser/Hewitt 2003 Survey on Retiree Health Benefits." The Kaiser Family Foundation and Hewitt Associates, January 14, p. 33. (http://www.kff.org/medicare/011404package.cfm). Retrieved April 27, 2004. 17 O'Sullivan et al. (2003). "Overview of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003." Congressional Research Service, December 9, p. 11. 18 Kaiser Family Foundation (2004). "Medicare at a Glance." March. (http://www.kff.org/medicare/1066-07.cfm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 19 U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (2004). "New Molecular Entities (NMEs) Approved in Calendar Years 2002, 2003." (http://www.fda.gov/cder/rdmt/default.htm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 20 Carpenter, Daniel P. (2004). "The Political Economy of FDA Drug Review: Processing, Politics, and Lessons for Policy." Health Affairs, 23(1), p. 58, 59. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 21 Cockburn, Iain M. (2004). "The Changing Structure of the Pharmaceutical Industry." Health Affairs, 23(1), p. 12. (www.healthaffairs.org). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 22 O'Reilly, Bill (1991). "Drugmakers Under Attack: Marketing Muscle, Patent Protection, and A Unique Relationship with Consumers Have Made Them America's Most Profitable Industry" Fortune. 124 (3), p. 48. Retrieved May 27, 2004. ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM For updates, go to www.allhealth.org Prescription Drugs 3 6 61 Prescription Drugs CHAPTER 6 23 Schacht, Wendy H. & John R. Thomas. (2002). "The 'Hatch-Waxman' Act: Selected Patent-Related Issues." Congressional Research Service, April, p. 2. 24 Schacht, Wendy H. & John R. Thomas. (2004). "The Hatch-Waxman Act: Legislative Changes Affecting Pharmaceutical Patents." Congressional Research Service, February 19, p. 6, 7. 25 National Conference of State Legislatures (2004). "Recent Medicaid Prescription Drug Laws and Strategies, 2001-2003." March 1. (www.ncsl.org/programs/health/medicaidrx.htm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 26 National Conference of State Legislatures (2004). "State Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs." April 20. (www.ncsl.org/programs/health/drugaid.htm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 27 National Conference of State Legislatures (2004). "State Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs." April 20. (www.ncsl.org/programs/health/drugaid.htm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 28 National Conference of State Legislatures (2004). "Recent Medicaid Prescription Drug Laws and Strategies, 2001-2003." March 1. (www.ncsl.org/programs/health/medicaidrx.htm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 29 National Conference of State Legislatures (2004). "Recent Medicaid Prescription Drug Laws and Strategies, 2001-2003." March 1. (www.ncsl.org/programs/health/medicaidrx.htm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 30 Department of Health and Human Services (2004). "HHS Approves First-Ever Multi-State Purchasing Pools for Medicaid Drug Programs." News Release, April 22. (www.dhhs.gov/news/press/2004pres/20040422.html). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 31 Tedeschi, Bob (2004). "Looking to Canadian Web Pharmacies for Savings." New York Times, March 8. (www.nexis.com). 32 Hughes, Bonnie & Nicole C. Pyhel, eds. (2003). "Drug Companies May Be Headed for a Bruising Battle as Drug Reimportation Grows," The Wall Street Journal Online, October 9, p. 1. (http://www.harrisinteractive.com/news/newsletters/wsjhealthnews/WSJOnline_HI_Health-CarePoll2003vol2_iss8.pdf). 33 IMS Health. (2004). "IMS Reports 11.5 Percent Dollar Growth in '03 U.S. Prescription Sales." News release, Feb. 17. (www.imshealth.com). 34 Pear, Robert (2004). "U.S. to Study Importing Canada Drugs but Choice of Leader Prompts Criticism." New York Times, Feb. 25. (www.nexis.com). 35 Congressional Budget Office (2004). "Would Prescription Drug Importation Reduce U.S. Drug Spending?" April. (http://www.allhealth.org/recent/audio_07-22-04/CBOPrescriptionDrugImportation.pdf). Retrieved May 15, 2004. 36 Kerry/Edwards Campaign (2004). "A Plan for Stronger, Healthier Seniors." (www.johnkerry.com/issues/health_care/seniors.html). Retrieved July 26, 2004. 37 Office of Senator Charles Grassley (2004). "Grassley says it should be legal to buy prescription drugs from Canada." Press Release, April 8. (http://grassley.senate.gov/releases/2004/p04r04-08a.htm). Retrieved May 18, 2004. 38 "Kerry Health Plan Would Force Drugmakers to Accept Lower Prices," Bloomberg.com, Aug. 2, 2004, (http://quote.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=71000001&refer+us&sid=aPeiNICRh3KA) Retrieved Aug. 24, 2004. 39 George W. Bush 2004. "Making Health Care More Accessible and Affordable," (www.georgebush.com/healthCare/Brief.aspx) Retrieved. 23, 2004. 6 62 SOURCEBOOK FOR JOURNALISTS, 2004 For updates, go to www.allhealth.org ALLIANCE FOR HEALTH REFORM