Workbook PDF - SmartPros Accounting

advertisement

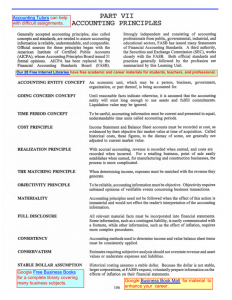

ADP Lunch & Learn RRR Course Materials Going Concern: The Growing Concern NASBA INFORMATION SmartPros Ltd, producer of this CPE program, is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a Quality Assurance Service (QAS) sponsor of continuing professional education, (QAS Sponsor #009). State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding QAS program sponsors may be submitted to NASBA through its website: www.learningmarket.org. ADP has partnered with SmartPros to provide this program and SmartPros has prepared the material within. www.smartpros.com 101512 segment one segment one segment one 1 1. Going Concern: The Growing Concern Learning Objectives: Upon successful completion of this segment, you should be able to: • explain the going-concern assumption; • define “foreseeable future” for purposes of going concern; • distinguish between IFRS and GAAP in terms of management’s responsibility for going concern; • identify the objectives of FASB’s project on risks and uncertainties. Segment Overview: Even though the going-concern assumption is universally understood and accepted by accounting professionals, it has never been formally incorporated into U.S. GAAP. Loscalzo Associates’ Bruce Pounder provides us with an update on the responsibility of both auditors and management in assessing an entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. Field of Study: Auditing Course Level: Course Prerequisites: Advance Preparation: Recommended Accreditation: Required Reading (Self-Study): Update Work experience in financial reporting or auditing, or an introductory course in accounting None 1 hour group live 2 hours self-study “The Going-Concern Assumption: Its Journey into GAAP” By Professor William Hahn, Southeastern University Excerpted with permission of The CPA Journal For additional information, go to: www.cpajournal.com “FASB Proposes Requirements for the Liquidation Basis of Accounting” By Robert P. Skubic, KPMG Department of Professional Practice Excerpted with permission of Defining Issues For additional information, go to: www.kpmginstitutes.com/financial-reporting-network See page 11. Video Transcript: See page 18. Running Time: 27 minutes outline outline outline outline outline 2 Outline I. Going-Concern Assumption A. SAS No. 59 1. Provides U.S. guidance a. on entity’s ability to continue as a going concern 2. Substantial doubt for a reasonable period a. not more than one year B. New FASB Project on Risks and Uncertainties 1. Develop principle for entity to determine adequacy of disclosures 2. Evaluate how to improve content of disclosures C. Going Concern Assumption 1. Underlying tenet of GAAP 2. Entities are going to be in existence a. for foreseeable concept D. Auditors’ Expression of “Substantial Doubt” 1. Over GM’s ability to continue as going concern in 2009 2. Required reporting under SAS No. 59 II. Responsibility for “Going Concern” A. U.S. GAAP 1. Management has no responsibility a. to disclose observations about going concern B. Under IFRS 1. Management must express concerns a. about entity’s ability to continue as going concern C. Under IAASB 1. Auditors must consider appropriateness a. of management’s going concern assumption D. What Is Considered in Going Concern Assessment 1. IFRS: no limit as to what management should consider 2. SAS No. 59: auditors primarily consider financial statements E. If FASB Incorporates Going Concern in GAAP 1. It may also remain in auditing standards under GAAS 2. Financial statement users want audit of management’s disclosures outline outline outline outline outline 3 Outline (continued) III. Making a Going Concern Assessment A. Dimensions of Standard Setting on Going Concern 1. Who is responsible for making assessment? 2. What information goes into assessment? 3. How far in future should assessment look? B. “Foreseeable Future” for Going Concern Assessment 1. U.S. auditing standard: 12-month maximum 2. IFRS: no limit on time period 3. Proposed GAAP by FASB: 12month minimum C. Change in FASB Attitude toward Going Concern 1. “We need to get this guidance into GAAP” 2. “No, we don’t” 3. “We’re looking at the issue again” D. Role of Management vs. Role of Auditor 1. Even when going concern is management’s responsibility a. people lack confidence in management’s candor 2. Value in requiring auditors to consider appropriateness a. of management’s going concern assumption IV. Risk and Uncertainties A. Disclosures about Risk and Uncertainties 1. Are important 2. Are different than assessment of going concern B. Management’s Disclosure of Risk and Uncertainties 1. May not provide a basis for conclusion about going concern C. Liquidation Basis of Accounting 1. Used when entity is NOT a going concern 2. Presents assets and liabilities at net realizable values D. FASB: Use Liquidation Basis 1. If liquidation is imminent 2. Whether liquidation is a. voluntary b. compelled c. secretly planned 3. What are potential “triggers” or considerations? outline outline outline outline outline 4 Outline (continued) V. Going Forward with Going Concern A. Progression of FASB guidance 1. Going concern: intended to mirror IFRS 2. Risk and uncertainties: would not converge standards a. one of several areas without convergence C. Policy Considerations 1. Disclosures on risk and uncertainties will not provide a. same level of conclusiveness as adverse going concern 2. Is it possible for FASB to avoid “disclosure overload”? B. For Disclosures on Risk and Uncertainties 1. How do you measure risk? 2. How do you communicate risk? VI. The Future of Convergence A. Convergence of Accounting Languages 1. Current rules: public companies must use GAAP a. in financial statements submitted to SEC 2. Proposed condorsement: continuation of use of GAAP a. rather than “wholesale switch” to IFRS B. Frustration over Convergence Process 1. Based on target dates, rather than deadlines 2. Keep “resetting” target dates 3. Processes may not be effective in dealing with convergence C. Likely Scenarios 1. Time to “hedge” bets on convergence? 2. SEC a. may not require U.S. companies to switch to IFRS b. may allow U.S. companies to switch to IFRS discussion questions discussion questions 5 Group Discussion Instructions for Segment • As the Discussion Leader, you should introduce this video segment with words similar to the following: “In this segment, Bruce Pounder explains the responsibility of auditors and management in assessing an entity’s ability to continue as a going concern.” • After playing the video, use the questions provided or ones you have developed to generate discussion. The answers to our discussion questions are on pages 7 and 8. Additional objective questions are on pages 9 and 10. • Show Segment 1. The transcript of this video starts on page 18 of this guide. Discussion Questions 1. Going Concern: The Growing Concern You may want to assign these discussion questions to individual participants before viewing the video segment. 1. Bruce Pounder believes that accountants have an inherent understanding of the going-concern assumption: that entities are going to be in existence for the foreseeable future. Do you agree with their observation? To what extent do you consciously recall that financial reporting is based on the fact that a business is expected to survive for the foreseeable future? 2. Bruce Pounder cites the going-concern modification for General Motors as an indication that more attention is paid to going concern during economic recessions. Do you agree with his observation? To what extent have you had discussions during the recent recession considering the going concern status of your clients’ entities, of your clients’ suppliers/vendors, or of your clients’ customers? 3. Does the management of your clients’ organizations feel responsible for making an assessment of going concern? To what extent have you (or your firm) considered issuing a goingconcern modification in recent years? 4. What information do you (or your firm) consider in making a going concern assessment of your organization? What information should be considered? To what extent do you, or should you, consider nonfinancial information, such as the viability of a business plan? 5. How far into the future do you (or your firm) look in making a going concern assessment of your clients? How far should you look? To what extent do you, or should you, consider events that are more than one year away? discussion questions discussion questions 6 Discussion Questions (continued) 6. Under FASB’s guidance, when should a business use the liquidation basis of accounting? How does it differ from GAAP? Are you familiar with any companies (or clients) that have used the liquidation basis? 7. On one hand, FASB’s project on risk and uncertainties aims to “evaluate how to improve the content of business disclosures.” On the other hand, many observers – including FASB’s own chair – believe that we suffer from “disclosure overload.” From your perspective, do we require companies to disclose too much information? How do you balance the needs of financial statement users with management’s responsibilities? suggested answers to discussion questions Suggested Answers to Discussion Questions 1. Going Concern: The Growing Concern 1. Bruce Pounder believes that accountants have an inherent understanding of the going-concern assumption: that entities are going to be in existence for the foreseeable future. Do you agree with their observation? To what extent do you consciously recall that financial reporting is based on the fact that a business is expected to survive for the foreseeable future? • Participant response is based on your background (education and values), your perspective (clients and practice structure), and your experience (engagements). 2. Bruce Pounder cites the going-concern modification for General Motors as an indication that more attention is paid to going concern during economic recessions. Do you agree with his observation? To what extent have you had discussions during the recent recession considering the going concern status of your clients’ entities, of your clients’ suppliers/vendors, or of your clients’ customers? • Participant response is based on your background (education and values), your perspective (clients and practice structure), and your experience (engagements). 3. Does the management of your clients’ organizations feel responsible for making an assessment of going concern? To what extent have you (or your firm) considered issuing a goingconcern modification in recent years? • Participant response is based on your background (education and values), your perspective (clients and practice structure), and your experience (engagements). 4. What information do you (or your firm) consider in making a going concern assessment of your organization? What information should be considered? To what extent do you, or should you, consider nonfinancial information, such as the viability of a business plan? • Participant response is based on your background (education and values), your perspective (clients and practice structure), and your experience (engagements). 5. How far into the future do you (or your firm) look in making a going concern assessment of your clients? How far should you look? To what extent do you, or should you, consider events that are more than one year away? • Participant response is based on your background (education and values), your perspective (clients and practice structure), and your experience (engagements). 6. Under FASB’s guidance, when should a business use the liquidation basis of accounting? How does it differ from GAAP? Are you familiar with any companies (or clients) that have used the liquidation basis? • Liquidation basis of accounting is used only when an entity is NOT a going concern, because liquidation is imminent. • It differs from GAAP in the sense that assets and liabilities are presented at net realizable values. • Participant response is based on your background (education and values), your perspective (clients and practice structure), and your experience (engagements). 7 suggested answers to discussion questions 8 Suggested Answers to Discussion Questions 7. On one hand, FASB’s project on risk and uncertainties aims to “evaluate how to improve the content of business disclosures.” On the other hand, many observers – including FASB’s own chair – believe that we suffer from “disclosure overload.” From your perspective, do we require companies to disclose too much information? How do you balance the needs of financial statement users with management’s responsibilities? • Participant response is based on your background (education and values), your perspective (clients and practice structure), and your experience (engagements). 9 objective questions objective questions Objective Questions 1. Going Concern: The Growing Concern You may want to use these objective questions to test knowledge and/or to generate further discussion; these questions are only for group discussion purposes. Most of these questions are based on the video segment; a few may be based on the required reading for self-study that starts on page 11. 1. Under IFRS, a company’s management analyzes _________ in order to assess their company’s ability to continue as a going concern. a) all available information b) working capital deficiencies c) the entity’s business model d) relevant external factors 2. Now that FASB’s going concern project has gone in a different direction, it is likely to result in: a) convergence with the IFRS going concern requirements. b) management being responsible for assessing going concern in the U.S. c) continued differences between GAAP and IFRS over going concern. d) a 3-year timeframe for events to be considered for a going concern assessment. 3. The main reason for concern over management’s responsibility for the going concern assessment is: a) the ASB believes this role should remain only with the auditors. b) the public does not trust company management to be completely candid. c) the SEC believes that public companies need separate guidance in this area. d) Canada and other countries have had difficulty in implementing the IFRS model. 4. A roadblock to adopting IFRS goingconcern guidance in the U.S. has been: a) the auditing profession’s resistance to any change. b) companies’ need for principle-based guidance. c) the nature, and litigiousness, of U.S. society. d) FASB’s desire to avoid convergence with IFRS. 5. According to Bruce Pounder, FASB’s proposed risk and contingency disclosures are: a) unnecessary. b) tantamount to a going concern assessment. c) do not provide a going concern assessment. d) likely to be converged with IFRS. 6. Bruce Pounder believes the liquidation basis of accounting is similar to: a) GAAP. b) income tax basis. c) modified cash basis. d) none of the above. 7. Ultimately, Bruce Pounder envisions a situation where the SEC: a) may not require public companies to switch to IFRS. b) may allow U.S. companies to switch to IFRS. c) will require public companies to switch to IFRS. d) both a) and b), but not c). 8. According to the required reading, the first documented use of the term “going concern” was traced to: a) Henry Rand Hatfield. b) Lawrence Dicksee. c) John R. Commons. d) the Committee on Accounting Procedure. objective questions objective questions 10 Objective Questions (continued) 9. According to the required reading, FASB’s original proposed going concern standard elicited all of the following concerns except: a) concern that “all available information” to be considered by management was too broad. b) doubt about the appropriateness of incorporating the going concern guidance into GAAP. c) concern that the time frame for consideration of going concern issues was too long and open-ended. d) concern over conflicting disclosure requirements between the proposal, IAS 1, and AU section 341. 10. According to the required reading, under which of the following circumstances would the liquidation basis of accounting be inappropriate? a) A liquidation that is expected to conclude earlier than the contractually stated expiration date of the entity b) An involuntary bankruptcy c) A liquidation that takes place pursuant to an entity’s governing documents d) A liquidation approved by management and unlikely to be blocked by other parties required reading required reading 11 Self-Study Option Instructions for Segment When taking a segment on a self-study basis, an individual earns CPE credit by doing the following: 1. Viewing the video (approximately 25 minutes). The transcript of this video starts on page 18 of this guide. 3. Completing the online steps (approximately 55 minutes). 2. Completing the Required Reading (approximately 20 minutes). The Required Reading for this segment starts below. Required Reading (Self-Study) THE GOING-CONCERN ASSUMPTION: ITS JOURNEY INTO GAAP By Professor William Hahn, Southeastern University Excerpted with permission of The CPA Journal For additional information, go to: www.cpajournal.com whether there is substantial doubt about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern for a reasonable period of time.” If there is substantial doubt, an explanatory paragraph should be included in the auditors’ report. The going-concern assumption is universally understood and accepted by accounting professionals. Indeed, the assumption of a going concern is critical to the decision usefulness of financial information under the accrual basis of accounting. It is also the justification for valuing most assets at historical cost. It has, however, received little attention in the accounting literature and has never been formally incorporated into U.S. GAAP. This responsibility often places an auditor in an uncomfortable position with clients. Research conducted by Audit Analytics reveals that, over a 10-year period (2000–2009), an average of 18.5% of all audit opinion letters included a goingconcern modification. This is about 2,950 modifications each year for SEC filers. Even though users understand that management is responsible for the form and content of a business’s financial statements, there is no official guidance requiring management to assess their entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. Currently, AU section 341 provides the only formal guidance in this area. This section states, in part, that “the auditor has a responsibility to evaluate Short History of the GoingConcern Assumption The first documented use of the term “going concern” was traced by economist John R. Commons to a 1620 lawsuit in which the value of assets was in dispute. In this lawsuit, the court distinguished between a going-concern value and a value tantamount to the current concept of historical cost. required reading required reading 12 Following the 1620 case, the going-concern idea remained mainly in the legal domain (primarily related to entity value determination) until 1892, when Lawrence R. Dicksee published Auditing: A Practical Manual for Auditors. As reported by R.K. Storey, Dicksee argued that assets should be valued on a going-concern basis and not adjusted for “a fluctuation in value caused by external circumstances.” Clearly, Dicksee viewed the going-concern idea as a basis for accounting for assets using historical costs. While the literature is incomplete on how the going-concern idea was presented and debated after Dicksee’s book formalized the discussion in 1892, Storey reports that the next major step was Henry Rand Hatfield’s 1909 book, Modern Accounting: Its Principles and Some of Its Problems, which included the going-concern assumption. In a 1927 book, Accounting: Its Principles and Problems, Hatfield expanded his discussion of the goingconcern assumption, indicating that the concept was generally accepted among practicing accountants of that era. Remember, there was no formal standardssetting body at the time Dicksee and Hatfield were writing about the goingconcern assumption. While groups that were precursors of the AICPA existed between 1887 and 1939, the first formal group to promulgate accounting principles was the Committee on Accounting Procedure (CAP), which was a subgroup of the American Institute of Accountants (the forerunner of today’s AICPA). The CAP issued 51 Accounting Research Bulletins (ARB) between 1939 and 1959. The first introduction of the going-concern assumption into the formal accounting literature occurred in 1953, when the CAP issued ARB 43, Restatement and Revision of Accounting Research Bulletins. In chapter 3, section A, “Current Assets and Current Liabilities,” of that bulletin, the CAP asserted: “It should be emphasized that financial statements of a going concern are prepared on the assumption that the company will continue in business.” This assertion established the importance of continuity as a basis for the decision usefulness of financial statements. In 1961, the AICPA issued Accounting Research Study 1, The Basic Postulates of Accounting. In this document, crafted by Maurice Moonitz, postulate C-1 states the following: Continuity (including the correlative concept of limited life). In the absence of evidence to the contrary, the entity should be viewed as remaining in operation indefinitely. In the presence of evidence that the entity has a limited life, it should not be viewed as remaining in operation indefinitely. The continuity postulate was listed along with objectivity, consistency, stable measuring unit, and disclosure as essential to effective accounting and financial reporting. In 1978, FASB issued Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts (SFAC) 1, Objectives of Financial Reporting by Business Enterprises. Paragraph 42 of this statement states the following: Financial reporting should provide information about an enterprise’s financial performance during a period. Investors and creditors often use information about the past to help in assessing the prospects of an enterprise. Thus, although investment and credit decisions reflect investors’ and creditors’ expectations about future enterprise performance, those expectations are commonly based at least partly on evaluations of past enterprise performance. It is only in footnote 10 of SFAC 1 that the going-concern assumption is mentioned. Footnote 10 states, in part, the following: Investors and creditors ordinarily invest in or lend to enterprises that they expect to continue in operation – an expectation that is familiar to accountants as “the going concern” assumption. In 1989, the AICPA issued Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) 59, The Auditor’s Consideration of an Entity’s Ability to Continue as a Going Concern (later incorporated in AU section 341), required reading required reading 13 which, as previously discussed, placed the burden of a going concern determination on the auditor. Paragraph .02 states the following: The auditor has a responsibility to evaluate whether there is substantial doubt about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern for a reasonable period of time, not to exceed one year beyond the date of the financial statements being audited (hereinafter referred to as a reasonable period of time). As the international standards convergence movement gathered momentum, the AICPA and FASB moved to formalize the goingconcern assumption into published guidance. The AICPA included a goingconcern requirement in its 2008 Omnibus Statement on Standards for Accounting and Review Services (SSARS) 17. This section, in paragraph 69, added the following language: During the performance of compilation or review procedures, evidence or information may come to the accountant’s attention indicating that there may be an uncertainty about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern for a reasonable period of time, not to exceed one year beyond the date of the financial statements being compiled or reviewed (hereinafter referred to as a reasonable period of time). In those circumstances, the accountant should request that management consider the possible effects of the going concern uncertainty on the financial statements, including the need for related disclosure. Finally, in 2008 FASB issued its proposed SFAS, Going Concern, discussed below. Proposed Going-Concern Standard The proposed statement on going concern has been in exposure draft form since October 9, 2008, and the impetus for its issuance is the convergence with international standards. The language set forth in the exposure draft is almost identical to that of sections 25 and 26 of International Accounting Standard (IAS) 1, Presentation of Financial Statements. There are only two areas of difference between the standards. First, there are a few phrasing differences which are simply a matter of writing style. Second, the guidance is presented in two paragraphs in the international standard, whereas it is in four paragraphs (three, four, seven, and eight) in the proposed standard. Paragraph three of the proposed guidance clearly establishes responsibility in this area. Paragraph three states, in part, that “management shall assess the reporting entity’s ability to continue as a going concern.” Paragraph four suggests a minimum 12-month forward time horizon over which management should evaluate “current and expected profitability, debt repayment schedules, and potential sources replacement financing” as aspects of a comprehensive going concern assessment. If, after such assessment, management concludes that there is substantial doubt as to the organization’s ability to continue as a going concern, it must disclose that conclusion. In addition, the proposed standard requires that management set forth the reasons why such a determination was made, as well as the basis upon which the current-year financial statements are presented. In a going-concern assessment, paragraph five of the exposure draft sets forth examples of events that, either individually or in concert with each other, could lead management to conclude that substantial doubt exists as to the ability of an organization to continue as a going concern. Examples provided by FASB are negative performance trends in the areas of profitability or cash flow, as well as significant events such as a regulatory order, loan default, or creditor unwillingness to engage in business. In addition, internal operational problems and “external matters such as legal proceedings, legislation, loss of a key business franchise, license, or patent, customer, or environmental occurrence” may contribute to management’s determination. If such a determination is made, paragraph six required reading required reading 14 provides specific information management should consider in deciding how to deal with the conditions and events that inhibit going-concern capacity as well as the likelihood that such plans can be implemented successfully. Should management conclude that substantial doubt exists as to the ability of an organization to continue as a going concern, paragraph seven of the proposed standard requires the disclosure of the basis for such an assessment and any course of action that management plans to pursue in order to attempt to return the organization to going concern status. Comments on the Exposure Draft Those responding to the exposure draft generally agreed with FASB’s proposed move to include a going-concern assessment in GAAP. Nevertheless, concerns were expressed in four areas: 1) the types of information required as part of management’s assessment, 2) the time horizon over which such an assessment must be made, 3) specific disclosure requirements, and 4) the definition of a going concern. 1) Types of information required. The first area of concern revolves around a change in wording from AU section 341 to the proposed standard. In paragraph .02 of AU section 341, an auditor is required to consider “knowledge or relevant conditions and events that exist at or have occurred prior to the date of the auditor’s report,” whereas the proposed standard (paragraph four) requires management to consider “all available information about the future.” Commenters argued that the “all available information” wording was too broad and implied that management would need to assess unlimited amounts of information into an unforeseeable future. Others contended that the cost of conducting a going concern assessment of the scope required by the exposure draft would be too high with respect to the benefits realized from such an assessment. Finally, some thought that the wording would result in inconsistent application in practice. FASB decided to modify paragraph four of the proposed standard by removing the word “all.” As revised, this aspect of the standard will read “management shall take into account available information.” 2) Time horizon. The time horizon set forth in the exposure draft drew the most attention from commenters. Critics argued that the time horizon is too long and too nebulous, that it will be difficult for practitioners to apply, that the language conflicts with time frames set forth in GAAS, and that the proposed time frame could have legal ramifications. The areas of greatest concern were the workability of the open-ended time frame in the U.S. legal environment and an apparent conflict with currently existing auditing guidance that uses a one-year time frame (e.g., SOP 94-6, Disclosure of Certain Significant Risks and Uncertainties; SFAS 6, Classification of Short-Term Obligations Expected to Be Refinanced; and AU section 341). FASB decided to modify the time frame so that events beyond one year in the future must be compelling if they are to be considered in the going-concern assessment. In their rationale for this change in language, FASB indicated that the definition is not intended to be openended or indefinite. To clarify this intent, the first two sentences of paragraph four will be changed to read as follows: In assessing whether the going-concern assumption is appropriate, management shall take into account available information about the foreseeable future, which is generally, but not limited to, 12 months from the end of the reporting period. Certain events that are expected to occur or are reasonably foreseeable beyond 12 months, and would materially affect the assessment, are considered part of the foreseeable future. The time frame beyond 12 months is limited to a practical amount of time thereafter in which significant events or conditions that may affect the evaluation can be identified. required reading required reading 15 Thus, 12 months was set as the workable time frame, but FASB’s modification allows for professional judgment in extending the time frame beyond 12 months, based on known facts and circumstances. 3) Disclosure requirements. A third area of concern is related to the disclosure of goingconcern circumstances. Commenters pointed out that there is inconsistency between the proposed disclosures and those in IAS 1, as well as the omission of certain disclosures currently set forth in AU section 341, paragraph 11. Respondents also noted that it was unclear as to whether disclosures were required in each year’s annual report only if there is doubt as to an organization’s ability to continue as a going concern. Finally, it was suggested that the proposed language be changed to explicitly state that management had made a determination as to goingconcern status. At its January 13, 2010, meeting, FASB considered the use of the term “substantial doubt” as it appears in paragraph seven of the exposure draft. Based on the comments received, the board concluded that the language should be modified. The two possibilities under consideration are: “it is more than remote that the entity will not continue as a going concern,” and “it is more likely than not that the entity may not continue as a going concern.” 4) Going concern definition. Finally, the proposed standard does not contain a definition of a going concern. Commenters suggested that FASB include a definition in order to provide the clarity that would remove judgment and uncertainty in this area. Journey’s End Whenever issued, the going-concern guidance will appear in the Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) section 205, “Presentation of Financial Statements.” For example, section 205-30-45-1, “Other Presentation Matters,” is proposed to read, in part: When preparing financial statements, management shall assess the reporting entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. An entity shall prepare financial statements on a going concern basis unless management either intends to liquidate the entity or to cease operations or has no realistic alternative but to do so. FASB PROPOSES REQUIREMENTS FOR THE LIQUIDATION BASIS OF ACCOUNTING By Robert P. Skubic, KPMG Department of Professional Practice Excerpted with permission of Defining Issues For additional information, go to: www.kpmginstitutes.com/financial-reportingnetwork The FASB recently issued a proposed Accounting Standards Update (ASU) that would provide guidance about when an entity would be required to prepare its financial statements using the liquidation basis of accounting. Under that accounting basis, an entity would be required to measure and present assets and liabilities at the estimated amount of cash that the entity expects to collect or pay to settle its obligations during liquidation. Comments are due by October 1, 2012. Current U.S. GAAP provides minimal guidance about applying the liquidation basis of accounting. The proposed ASU’s objective is to eliminate diverse practices by providing guidance about when it is appropriate to apply the liquidation basis of accounting and how to apply it. Originally, an additional objective of the project was to incorporate current auditing guidance on reporting when there is doubt about an entity’s ability to continue as a going required reading required reading 16 concern and to determine whether or not U.S. GAAP should require management to assess if the entity will be able to continue as a going concern, and if so, how it should conduct the assessment. However, the FASB subsequently decided to separate the deliberations related to the liquidation basis of accounting from those related to the going concern assessment. The FASB will address going concern considerations as the second phase of the project on management’s responsibility for going concern assessments. Liquidation Basis of Accounting Under the proposed ASU, the liquidation basis of accounting would be applied when liquidation is imminent. Liquidation would be considered imminent when either of liquidation is imminent. Liquidation would be considered imminent when either of the following occurs: • A plan of liquidation has been approved by the person or persons with the authority to make this plan effective and the likelihood is remote that the execution of the plan will be blocked by other parties (e.g., those with protective rights); or • A plan for liquidation has been imposed by other forces (e.g., involuntary bankruptcy) and the likelihood is remote that the entity will return from liquidation status. If a plan for liquidation is specified in an entity’s governing documents at its inception (e.g., limited-life entity) and liquidation will occur under the original plan, the liquidation basis would not be applied. Instead, liquidation would be considered imminent for such entities if significant management decisions about furthering the ongoing operations of the entity have ceased or they are substantially limited to those necessary to carry out a plan for liquidation other than the plan specified at inception (i.e., there have been substantial changes in its original limitedlife plan). The proposed ASU includes a list of indicators that imply a plan for liquidation might differ from what was specified in the governing documents: • The date that liquidation is expected to conclude is earlier or later than the contractually stated expiration date of the entity. • The entity is forced to dispose of its assets in a manner that is not orderly or in exchange for consideration that is not commensurate with the fair value of the assets. • The entity’s governing documents have been amended since inception. Financial statements prepared under the liquidation basis of accounting would reflect an entity’s resources and obligations in liquidation by measuring and presenting assets and liabilities in the entity’s financial statements at the estimated amount of cash or other consideration that the entity expects to collect or pay to carry out its liquidation plan. Liquidation amounts would not necessarily be expected to be at fair value and, therefore, the guidance on fair value measurement would not necessarily apply when estimating these amounts. Additionally, the measurement would include accrual of the estimated costs of disposing of assets and settling liabilities as well as accrual of the expected future costs and income to be incurred and generated through the date at which the entity expects to complete its liquidation. Effective Date and Transition The FASB has not determined a specific effective date. However, the proposed ASU would be effective as of the beginning of an entity’s first annual reporting period that begins after the effective date and for interim and annual periods thereafter. Early adoption would be permitted. The FASB will determine the effective date after it considers constituents’ feedback. required reading required reading 17 Separate FASB Project to Address Going Concern In May, the FASB decided to separate its project on liquidation basis of accounting and going concern into two phases. The proposed ASU addresses the first phase of the project. The objective of the second phase is to provide guidance about (1) whether and how an entity should assess its ability to continue as a going concern and (2) if so, the nature and extent of any related disclosure requirements. The Board directed the FASB staff to prepare materials to discuss at a future Board meeting but has not yet scheduled deliberations on the second phase. video transcript video transcript 18 Video Transcript 1. Going Concern: The Growing Concern LOOK: On one hand, it is management’s job to explain a company’s financial position to investors. But, on the other hand, there seems to be little faith – by regulators or by standard setters – in the ability of those executives to be candid when the company is in danger of “going under.” As a result, the FASB will not require management to assess whether there is substantial doubt about an entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. Earlier this year, the accounting standard setter announced that a majority of its board members determined that such a requirement would be difficult to apply. As a result, AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards No. 59, “The Auditor’s Consideration of an Entity’s Ability to Continue as a Going Concern,” continues to provide the U.S. guidance on this topic. Information obtained during a financial statement audit is the basis for this evaluation. SAS no. 59 states that the auditor is responsible for evaluating, whether there is substantial doubt about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern for a reasonable period, not more than one year beyond the date of the financial statements being audited. Under the FASB proposal, management would have been required to take into account all available information about the future, which was defined as at least – but not limited to – 12 months from the end of the reporting period. Instead, the FASB has redirected its project: One, to develop a principle for an entity to determine the adequacy of its disclosures about risks and uncertainties; and Two, to evaluate how the content of those disclosures could be improved. But the question remains: how do we give investors and other financial statement users fair warning when a company is in danger of “going under”? QUINLAN: That, indeed, is the question, Alice. And returning to our program – with the answer – is regular expert commentator Bruce Pounder, producer of “This Week in Accounting.” Thanks for joining us this month, Bruce. POUNDER: Glad to be back, Mike. QUINLAN: Let me start out with a baseline question for you, Bruce: it seems as if most accountants understand – and really accept – the going-concern assumption, doesn’t it? POUNDER: Accountants certainly do accept that assumption, maybe not very consciously though. It is “baked” into GAAP as a conceptual principle: there is an assumption that the entity will continue as a going concern, unless it becomes apparent otherwise. But because that is a relatively rare occurrence, or at least it is admitted relatively rarely, then we are video transcript video transcript 19 going to see, in most cases, companies will report on a going concern basis, that, is on the assumption that they are going to continue as going concerns. QUINLAN: Very few things in life are as inevitable as death and taxes. But one of those inevitabilities is the business cycle. There are going to be ups, and there are going to be downs. And whenever there are “downs,” it seems as if there are growing concerns over entities’ so-called going concern, doesn’t it? POUNDER: Absolutely, Mike. This is something that we see time and time again. We see it a little bit more in the downturns of the business cycle, and a little bit less when times are good. But it is always an issue and, certainly, one that users of financial statements in particular are always very concerned about. QUINLAN: That makes sense, Bruce, both historically and philosophically. But don’t I recall, just a few years ago, there was a great deal when Deloitte expressed its doubts about General Motors’ ability to continue as a going concern? POUNDER: That’s right, Mike. Back in 2009, Deloitte issued, as auditors are responsible for doing, an expression of substantial doubt about General Motor’s ability to continue as a going concern. In the United States, under Generally Accepted Auditing Standards, or GAAS, it is indeed the auditor’s responsibility to make that observation – and to include that in the auditor’s report – whenever they do have substantial doubt about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. QUINLAN: That’s obviously a concept that means something to auditors, as it did to Deloitte. But, in other countries, it’s up to the management of the entity to make that assessment of going concern, isn’t it, Bruce? POUNDER: It is, Mike. And that is where we see a difference between U.S. GAAP, the accounting standards that U.S. companies generally follow, and international financial reporting standards or IFRS. Under U.S. GAAP, there is no responsibility that the management of the entity has to make any sort of conclusion or observation about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. Whereas, under IFRS, it is a very different story. There is a very specific responsibility that management has to express any concerns that they do have about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. There are elements of that standard that are in the accounting set of rules under IFRS, which are complemented by a similar standard under the auditing rules that are also used on a global basis. So, one could say that there is a dual obligation of both the management of the entity, as well as the auditor of that entity’s books, to make that conclusion or make that observation about whether the entity is – or is not – able to continue as a going concern. QUINLAN: Let’s make sure I understand you, Bruce, in the context of management’s assessment of the entity’s ability to continue. What would management be looking at? Would they be examining operating losses and working capital deficiencies? Or would they be assessing the viability of a company’s business model? 20 video transcript video transcript POUNDER: Mike, the answer is pretty much “all of the above.” And the reason is, if you look at the standard in IFRS, what you are going to see is the responsibility for management to take into consideration all available information. That is a broad, open-ended way to look at what management might possibly be thinking of, or taking into consideration, when making that going concern assessment. There is no limit on it in terms of what the management of the entity is required under the accounting standard to consider. We have a very different situation in the United States. Since we do not have any sort of accounting standard in GAAP that puts the obligation on management to do a going concern assessment, all we have to look at is the auditing standard. In the case of the auditing standard, the amount of information – and the scope of information – that the auditor is required to consider is fairly limited, well defined, and narrowly defined, such that the auditor only has to take into consideration information that normally comes up in the course of the audit of financial statements. And that is typically not going to get into issues of strategy, business models, and external factors. These are not the sort of things then that auditors in the United States will be basing their assessment on, because the auditing standards here do not require that. QUINLAN: Interestingly, that’s what FASB proposed for U.S. GAAP: management would assess whether there’s substantial doubt about an entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. The idea was similar to “subsequent events,” wasn’t it, Bruce? It would become part of the accounting principles, but it would also remain a part of the auditing standards, too. POUNDER: Exactly. There have been discussions within the FASB – and between the FASB and auditing standard setting organizations, like the AICPA and the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) – as to where that sort of guidance belongs. Who should have the responsibility? If the FASB decides to put that within GAAP, so that management has the responsibility, there is certainly no assurance that the auditing standards will then drop it as a responsibility of the auditor. I think a lot of stakeholders, and a lot of users of financial statements, would go for the belt-and-suspenders approach, and they would like to see management have a responsibility for going concern as well as the auditor. QUINLAN: From the way I understand it, Bruce, both GAAP and FASB refer to the “foreseeable future” in terms of an entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. To what extent is there also some controversy over the time horizon? POUNDER: There has certainly been debate about that. It is a third key dimension of any standard that is placed on either management or the auditor for making a going concern assessment. The first dimension of the issue is, of course: who is responsible for it? The answer may be the auditor, management, or both, or neither. The second dimension, which we have discussed, is: how much information should whoever is responsible for making the going concern assessment consider in making that assessment? 21 video transcript video transcript And now, the third dimension is the time horizon. How far should that responsible party be looking forward into the future or when should that responsible party start? When should they stop looking in terms of the timeframe? Under existing GAAS in the United States, these are auditing standards putting responsibility on the auditor, but limiting the amount of information the auditor considers and also limiting that time horizon. The auditor would not normally look past 12 months beyond the date of the financial statements. That is what the standards prescribe. If you take a look at IFRS, it is a more open-ended sort of time horizon. If you look at what the FASB has proposed tentatively in the past, as they were more actively working towards creating guidance for U.S. GAAP to place a responsibility on management, we see many changes to the FASB’s tentative thinking actually over that time. The first idea was that the time horizon should be a minimum of 12 months under the accounting standards, versus the existing maximum of 12 months of auditing standards. And then, there was some pushback from constituents, not surprisingly, that opening the time horizon up indefinitely simply is not practical. And it might even lead to inconsistencies then from entity-to-entity into exactly how far forward the management or whoever would look. So, FASB has struggled with trying to define that time horizon in an appropriately broad, open-ended way, versus the practical considerations that constituents have or that an auditor or a manager of an entity would have, in saying, “Really, how far forward do I have to look?” It needs to be practical, as well as broad and inclusive. QUINLAN: Under one system, it is clearly management’s job to explain a company’s position to investors. But, under another way of looking at things, the regulators and standard setters have little faith in executives’ ability to be frank when the company is in danger of going under. From your perspective, Bruce, is one view more realistic than the other? POUNDER: What we see, Mike, is the FASB “flip-flop” on this issue over the past five years or so, going from the state – that we still have – of not having this kind of guidance in GAAP, to tentatively deciding, “We need to get this kind of guidance into GAAP.” And then, deciding, “No, we don’t.” And then, very recently, in May 2012: “Yeah, we’re going to look at this again because we’re back to thinking that we do need this guidance in the GAAP.” I think this back and forth over “do we” or “don’t we” reflects the tension that there is between two really fundamental concepts. On the one hand, you have a lot of folks who believe that it is management’s responsibility to communicate the financial position and financial performance of the entity. On the other hand, you have a lot of folks who believe that management cannot be trusted to tell the truth about financial position, financial performance and, particularly, about the outlook for the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. Well, if you take that latter view, then you are pretty much in line with the whole reason that we have external auditors in the first place. The fact that, even though it may be management’s responsibility or not, having an external, independent, objective source come in and assess the video transcript video transcript 22 reliability of whatever management does – or does not – assert is really a value-add for the capital markets. It really helps users of financial statements attribute the appropriate level of truthfulness to the assertions that management makes through the financial statements. If you believe, on one hand, that management really should be doing it. And you believe, on the other hand that, even though they are responsible for doing it, we cannot take them at their word. You are going to have this back-and-forth as these two ideas get to battle it out in the deliberations of the FASB and other organizations who are wrestling essentially with the same kinds of issues. So, it is really not too surprising, given the underlying conceptual conflict at play. QUINLAN: Okay, so FASB has decided to go in another direction. Instead of going concern, management is going to be asked to make ongoing disclosures about risks and uncertainties. To what extent is that the same thing as an assessment of going concern? POUNDER: I would really not consider them to be the same thing at all. When it comes to risks and uncertainties, these would be important disclosures for companies to make. But do they add up to an admission of a going concern issue? I do not think so. In this particular case, if what a user of the financial statements is concerned about is the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern, that would be very difficult for the user to tease out of very broad, very generic disclosures about risks and uncertainty. So, one of the key things about this project is whether disclosures about risks and uncertainty would be sufficient to enable a user of financial statements to reach a conclusion on his or her own about the entity’s ability to continue as a going concern. From my perspective, no, the risk and uncertainty disclosures would not enable users of financial statements to make those conclusions. QUINLAN: According to FASB, they’d like to “provide principles-based guidance on the adoption and application of the liquidation basis of accounting.” In the past, Bruce, you’ve told me about cash-basis and accrual-basis. Remind me: what do the standard setters mean when they refer to the “liquidation” basis of accounting? POUNDER: It is actually something that is not really parallel to the cash basis or income tax basis. It is its own whole other thing. The liquidation basis of accounting stands in contrast to the going concern basis of accounting. What most of us think of as accounting under GAAP is really a going concern basis of accounting. You can do that on an accrual basis. If you do not use GAAP, you can still make that same going concern assumption under a cash basis or income tax basis. But as soon as you cross the line and say, “We have some concerns about this entity’s ability to continue as a going concern,” then the issue of, “Maybe, we should be accounting for this in a completely different way is going to come up.” And that completely different way would really reflect what an entity would expect to get from selling off its assets and satisfying its liabilities, as opposed to continuing to use those assets and maintaining those liabilities as a going concern would do. video transcript video transcript 23 The basis for measuring assets and liabilities then can be extremely different from what the basis for measuring those balance items would be under a going concern assumption. QUINLAN: Okay, so, in FASB’s view – or in your view, Bruce – when is it appropriate for companies to use the liquidation basis of accounting: when an entity has actually filed for a liquidation or when it’s likely that outside forces are going to make them consider liquidating? POUNDER: I would say, from my perspective, that the FASB – in its tentative decisions to date – has pretty much come up with a practical line, and a useful line, where they say that: if liquidation is imminent, then that would be the trigger for switching from a going concern basis of accounting to a liquidation basis of accounting. What does it mean for liquidation to be imminent? One way that could happen is, if the management of the entity has deliberately taken steps to proceed with the liquidation. Or it could be an externally imposed situation, where it becomes obvious that the creditors of the entity are moving to force the liquidation of the entity. It could be associated with a bankruptcy filing on the part of the entity, although that – by itself, under our bankruptcy laws here in the United States – is not necessarily going to result in a liquidation. There could always be a situation where management secretly intends to liquidate and fails to disclose that fact, but rather than trying to split hairs or get inside of anyone’s mind, I think there are certainly obvious, observable events that take place, where one could objectively say, “Yes, a liquidation is imminent.” And certainly, under those situations, I would concur with the FASB in saying that is when you need to use the liquidation basis of accounting. There are “triggers” or considerations that you might look at and say, “Well, if this happens, then we should switch to the liquidation basis of accounting.” That is actually what the FASB right now is trying to decide and pin down. When exactly should an entity switch from a going concern basis to a liquidation basis? QUINLAN: As you just indicated, Bruce, FASB may – or may not – adopt new disclosures about risks and uncertainties. But, even if they do, there will still be a “gap” between the way “going concern” is treated under GAAP and the way it is treated under IFRS, won’t there? POUNDER: There will. In the past, the FASB has tried very hard to minimize that gap. Early on, when the FASB had made the decision that they were going to try to incorporate going concern guidance, and put management square in the “hot seat” with regard to responsibility for doing that, the FASB’s idea was very much to look at the existing guidance under IFRS and model FASB guidance after that. At this point, because the FASB has backed off of that and now it seems to be heading back in the direction of putting something into GAAP. I do not know if they are quite as enthused about the idea of minimizing any differences between whatever they come up with in GAAP and IFRS. That remains to be seen, but the potential is certainly there. If we look at other projects that the two boards have been working on which have had video transcript video transcript 24 the ostensible purpose of converging the two sets of standards at the standard level, convergence has not always been the outcome, at least not perfect convergence. In some cases, the boards remain fairly far apart. So, this is another project where we could get a very high degree of convergence – or not. QUINLAN: On one hand, disclosures regarding risks and uncertainty would not – as you indicated, Bruce – produce the equivalent of a going concern opinion. On the other hand, there’s also some controversy associated with those disclosures of risk and uncertainty, isn’t there? POUNDER: One of the things I would like to point out is that with the FASB’s recent thinking about disclosures regarding risks and uncertainty that, in itself, is a can of worms. We talked a little bit about how disclosures regarding risks and uncertainty would not produce the equivalent of an “adverse going concern” opinion in the same circumstances. One of the biggest problems with disclosures about risks and uncertainty is a question of: how do you measure risk? Even if you solve that: how do you communicate in an effective way things like risks and uncertainty to users of financial statements? These are not issues to resolve for any standard setter anywhere. There are challenges with how you measure risks. There are challenges with how you communicate risks and uncertainty, so these are difficult areas. What I know for certain, at least from my perspective, is you are never going to get the same level of conclusiveness from broad risk and uncertainty disclosures as you would get from a black-and-white adverse going concern opinion expressed by an auditor or by a manager of the entity. QUINLAN: I’ll ask you another “on the one hand” question, Bruce. On the one hand, many investors and financial statement users are always interested in getting increased disclosures from companies. On the other hand, even FASB is aware that we might be in a situation of “disclosure overload,” aren’t they? POUNDER: The inherent challenges of risk and uncertainty disclosures are simply compounded by the fact that, as is widely acknowledged, we are in a state of disclosure overload already. So, if risk and uncertainty disclosures were really the only new thing or the only substantial thing that was “on the table” in terms of standard setting, these might not be very significant issues. But in the context, and with the cumulative effect of all of the disclosures that are required under GAAP and similarly under IFRS today, adding more disclosures at this point in time is going to be looked at with an even more jaundiced eye than it normally would be. QUINLAN: Since the subject of convergence with IFRS is on the table, Bruce, I recall that – about a year or so ago – you told me about the word, “condorsement,” and about the significance of 2012 for producing a single set of high-quality global accounting standards. What’s going on? And why is this issue no longer on the “front pages”? POUNDER: “Condorsement,” Mike, as we discussed in the past, was a term coined by an SEC staff member to describe one possible way in which IFRS could be incorporated into the U.S. financial reporting environment, specifically for companies that are domestic SEC registrants – that is, video transcript video transcript 25 companies that are based here in the United States that are subject to the rules and regulations of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Right now, the rules and regulations are very clear. Such domestic registrants must use U.S. GAAP in preparing the financial statements that they’re required to submit to the SEC. Condorsement would be an approach where any changes to GAAP, as a result of convergence with IRFS at the standard level, would come through the FASB to be decided on an issue-by-issue basis: “whether this belongs in U.S. GAAP or not.” The interesting thing about the condorsement approach, which I said at the time and I still say, is that it would be, from the SEC’s perspective, a fundamental rejection of the use of IFRS by domestic SEC registrants. It would require the status quo. That is, domestic registrants would be required to continue using GAAP. The composition of GAAP would change, but it would not be a wholesale switch from U.S. GAAP to IFRS for domestic registrants. QUINLAN: Yes, on one hand, it does have a lot to do with the SEC and its agenda. But, on the other hand, I saw a recent report by FASB and the IASB to something called the Financial Stability Board. In that report, the two standard setters confirmed what you’re saying, Bruce: mid-2013 is the date they’re shooting for. Are the standard setters deliberately trying to sound more like diplomats when they talk about “working expeditiously towards a mutually satisfactory goal”? POUNDER: Yes, Mike, I think there is some very carefully chosen language there. This is a case where we have seen the standard setters repeatedly set targets for completing individual convergence projects in the past. Those targets have not been met. The targets have been reset. The reset targets have not been met. They have been reset again. The re-reset targets have not been met. So, the fact that there is a new target out there, which I think is fair to say is not a deadline. And these targets have not been considered by standard setters in the past as absolute deadlines, so these targets keep getting reset. They keep not getting met. And I think this is simply reflective of the challenges that the boards are facing and the challenges of the processes that they are using to try to resolve some pretty difficult issues. It has been my opinion, and I have expressed this publicly in the past, that I do not believe that the standard setting processes of the boards are as effective as they could be at dealing with what are admittedly very difficult standard setting challenges. QUINLAN: Well, you brought your crystal ball with you, Bruce. What does it say about the future of global accounting standards? POUNDER: I think we all have to take a look at the future in a kind of a betting way. There are a number of possibilities. How much are we willing to bet on any one of those possibilities? Maybe this is the time for us to hedge our bets and be more prepared for different scenarios that could unfold, each of which has a significant significance of unfolding. If I had to pick one scenario that I think is more likely that the others, but certainly not the only possibility and not the only one with a significant video transcript video transcript 26 possibility, simply a scenario more likely than any other scenario to happen, I would say that the SEC will not require domestic registrants to switch from using U.S. GAAP to using IFRS. I do, however, think that there is a decent likelihood of the SEC allowing domestic registrants their choice of using either IFRS or U.S. GAAP. QUINLAN: “This Week in Accounting’s” Bruce Pounder, thanks, once again, for bringing us up-to-date. POUNDER: Thanks, Mike. I would be glad to come back.