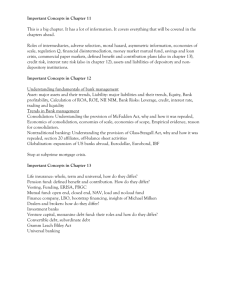

Chapter 2 Definitions and Accounting Principles

advertisement