Florida Transformative Education

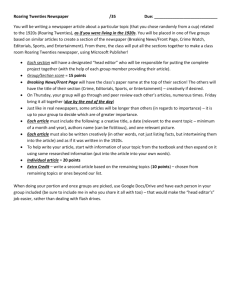

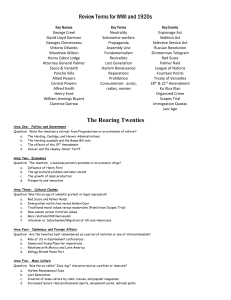

advertisement