Legal situation in the Member States of the European Union

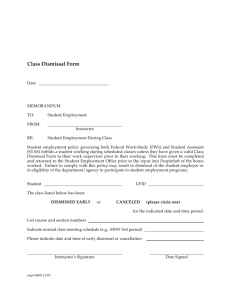

advertisement