Cecily Boulstred - Wicked Good Books

advertisement

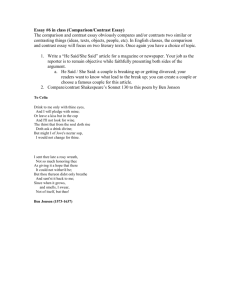

1 Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. Cecily Boulstred (1583-1609), Maiden of the Bedchamber Shee chang’d our world with hers. —John Donne, Elegie upon the Death of Mris Boulstred C ECILY BOULSTRED (commonly known as Cel or Celia) was the daughter of Edward and Cecily (Croke) Boulstred of Hedgerley Boulstred, in Buckinghamshire. The sixth of eleven children, Cecily was baptized at Beaconsfield on 12 February 1582/3. Nothing is known of her childhood. As a young adult, she became a noted wit in the court of James I. And in death, her body became a theme of court poets who competed for the literary matronage of Lucy Russell, countess of Bedford. 1 In 1602, Ben Jonson’s dearest friend, John Roe, courted Boulstred and received a pledge of her affection, possibly of marriage, but she ended the relationship. Shortly after the breakup, there circulated at court a verse epistle from John Roe addressed “To Mistress Boulstred.” The poem though scurrilous is written as if it were a moral remonstrance, addressed by a concerned male friend to a woman of easy virtue. It is alleged that Boulstred solicited Roe for sex, which caused him to reject her as unfit for marriage. The poet, who values the pleasures of friendship above those of fornication, professes himself unwilling to suffer a lifetime of remorse and possible damnation for one hour’s pleasure with a wanton courtesan: An Elegy to Mistress Boulstred, 1602 ˚ Shall I go force an elegy? abuse My wit, and break the hymen of my Muse For one poor hour’s love? Deserves it such, Which serves not me, to do on her as much? Or, if it could, I would that fortune shun! Who would be rich, to be so soon undone? The beggar’s best is, Wealth he doth not know (And but to show it him increaseth woe). But “We two may enjoy an hour”? When never It returns, who would have a loss for ever? Nor can so short a love, if true, but bring A half-hour’s fear with the thought of losing. Before it, all hours were hope; and all are That shall come after it, years of despair. This joy, brings this doubt: whether it were more To have enjoyed it, or have died before? ’Tis a lost Paradise, a fall from grace, Which I think Adam felt more than his race; Nor need those angels any other Hell: It is enough for them, from Heaven they fell. 2 3 4 1 Edward ] Edward Sr. died c. 1599; his principal heir, Edward (1588-1659) married Margaret Astley, daughter to the chamberlain of Queen Anna’s household. 2 Or, if ] And even if. 3 wealth he doth not know ] doesn’t know what he’s missing. 4 this joy…this doubt ] this joy of an hour’s sexual pleasure … this fear, that it were better to die innocent than to have illicit intercourse, and be damned. 2 • Women’s Works, vol. 3 • [25] 1 Beside, conquest in love is all in all! That, when I list, she under me may fall, 2 And for this, turn, both for delight and view? I’ll have a Succuba as good as you! But when these toys are past, and hot blood ends, The best enjoying is, we still are friends. Love can but be friendship’s outside; their two 3 Beauties differ, as minds and bodies do. Thus I this great good still would be to take 4 (Unless one hour, another happy make; Or, that I might forget it instantly; Or in that blest estate, that I might die). But why do I thus travail in the skill Of despised poetry? (and perchance spill My fortune, or undo myself in sport By having but that dangerous name in Court!) 5 I’ll leave. And since I do your poet prove, Keep you my lines as secret as my love. The disclaimer that “we still are friends” is a rhetorical ploy in the interest of slander: Roe after having been jilted speaks as a pious and congenial narrator even as he smears pitch on Boulstred’s reputation. That the poem is motivated by Roe’s “love” for Cecily is transparently insincere (“I’ll have a Succuba, as good as you”). Equally obvious: the poem was not kept “secret” – and it is beyond belief that Boulstred was herself the one who circulated the libel. Less obvious: “To Mistress Boulstred” was not, in fact, penned by John Roe. The verse circulated in manuscript as an epistle from “J.R.” to Boulstred. An attribution to Roe has never been challenged; but it was ghost-written by Ben Jonson, who years later quietly laid claim to it. Jonson often incorporated his earlier nondramatic verse into his new stageplays, which is precisely what he does with “To Mistress Boulstred,” in The New Inn (1628/9): Lovell. Who would be rich to be so soon undone? The beggar’s best is, wealth he doth not know: (And but to show it him, inflames his want). /…/ Host. These, yet, are hours of hope. Lovell. But all hours following Years of despair, ages of misery! Nor can so short a happiness, but spring A world of fear, with thought of losing it. Better be never happy, than to feel A little of it, and then lose it ever. /…/ If one hour could the other happy make, I should attempt it. /…/ (2.6) Lord Latimer. He lies With his own Succuba… (4.3) 1 conquest is all ] besides which, it’s no fun for the man if sex is freely offered and not won over her resistance. 2 when I list ] whenever I please; under me may fall ] 1. as a conquest; 2. in the missionary position; turn ] favor; sexual encounter. 3 Beauties ] the beauty of friendship, and the beauty of heterosexual love, are as different as mind and flesh. 4 5 this great good ] i.e., non-sexual friendship. dangerous name ] i.e., to be called a “poet”; cf. Epicœne: “It will get you the dangerous name of a Poet” (1.1). Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. 3 Nine years younger than Jonson, two years younger than Boulstred, John Roe was born in 1581 at Higham Hill, Essex. In 1597, he matriculated at Queen’s College, Oxford, but did not stay for a degree. The next few years took him to Russia and Ireland. In 1603, shortly after Boulstred sent him packing, Roe sold his inherited lands to his stepfather, Reginald Argall, for ready cash. With the proceeds, he bought himself a knighthood. (Ben Jonson describes Roe, his best friend, as “an infinite spender,” which may be one reason that Jonson loved him so well, and why Boulstred had second thoughts.) 1 On the accession of King James, Lucy Harington Russell, countess of Bedford, was appointed Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Anna. Still single, Cecily and Dorothy Boulstred (whose mother was first cousin to Lady Lucy), rose with her, to serve as Maidens of the Queen’s Bedchamber. The Boulstred sisters thereby leapt to prominence at Court while Sir John Roe was left in the cold. Sir John in the company of Ben Jonson again crossed paths with Celia Boulstred on 8 January 1603/4, at a lavish Hampton Court production of Samuel Daniel’s Vision of the Twelve Goddesses. Daniel’s masque that night was performed by Queen Anna, Lucy Russell, Frances Howard Seymour, and nine other goddesses of the Jacobean court. Penelope Rich for the occasion is said to have worn jewelry worth £20,000; her extravagant ornamentation was exceeded only by the queen, who is said to have worn £100,000 in gems (adjusted for inflation: roughly £20 million). 2 Before the evening was over, perhaps before the masque got started, Sir John Roe and Ben Jonson were expelled from the palace. Both men were escorted to the door by the Lord Chamberlain (Thomas Howard, earl of Suffolk), and threatened; a service that was performed by Suffolk at the behest of Jonson’s own literary matron, Lucy Russell. The offense was evidently something that Ben Jonson said to, or about, Cecily Boulstred (she, at least, is the person whom Jonson later blamed for the incident). Jonson resented having been “ushered” from Court (his word) or “thrust out” (Roe’s phrase). Fifteen years later and still fuming, Jonson told William Drummond “that Sir John Roe loved him; and when they two were ushered by my Lord Suffolk from [the] masque, Roe wrote a moral epistle to him,” with words of comfort and praise. Roe’s verse letter “To Ben Jonson,” dated January 1603/4, survives in multiple copies. In it, Roe counsels: “Forget we were thrust out! God threatens kings; kings, lords; as lords do us.” Roe praises Jonson and discounts the Court: “The State and men’s affairs are the best plays, / Next yours.”3 Roe digested the incident and moved on, but Jonson could not let it go. When he wrote the New Inn in 1628, the playwright not only adapted his 1604 lines “To Mistress Boulstred”; he revisited his embarrassment at Hampton Court, only to deny that it ever really bothered him: Lovell. If a woman or child Give me the lie, would I be angry? No, Not if I were i’ my wits, sure I should think it No spice of a disgrace. … If … I am kept out a masque, sometime thrust out, Made wait a day, two, three, for a great word, Which (when it comes forth) is all frown and forehead, What laughter should this breed, rather than anger! (4.4) Ben Jonson, by Isaac Oliver 1 infinite spender ] Drummond, 18. 2 goddesses ] The others were Katherine (Knyvett) Howard, countess of Suffolk; Elizabeth (Vere) Stanley, countess of Derby; Margaret (Stewart) Howard, countess of Nottingham; Penelope (Devereux) Rich, daughter of the countess dowager of Essex; Eliza (Cecil) Hatton, daughter of the earl and countess of Exeter; Audrey (Shelton) Walsingham, keeper of the Queen’s robes; Susan Vere (soon, countess of Montgomery by her marriage to Philip Herbert); Dorothy Hastings (daughter of the earl and countess of Huntington); and Elizabeth (Howard) Knollys (daughter of the earl and countess of Suffolk). Audrey (Shelton) Walsingham, Keeper of the Queen’s Robes, was the only one of the twelve performers who was not at least a countess or the unmarried daughter of a countess. 3 Sir John…epistle to him ] Drummond, 15; 1603[/4].” The State…next yours ] John Roe, “To Ben Jonson, 6 [i.e., 8] Jan. 4 • Women’s Works, vol. 3 • In May 1605, Sir John Roe left England to fight for the Protestant cause in the Low Countries (which is puzzling since Roe, like Jonson, was a Roman Catholic). On parting, he received a farewell gift, Casaubon’s edition of Perseus, inscribed by Jonson to his best-proved friend, his “Amico Probatissimo.” 1 Wounded in battle, Roe returned home in 1606 to resume his role as Jonson’s inseparable companion; and remained so until December 1608, when he died of the plague in the playwright’s embrace (Jonson’s unconfirmed report); whereupon Jonson underwrote the cost of Roe’s funeral. In one of three affectionate epigrams on his deceased friend, Jonson is unashamed to say that he decked the coffin of John Roe with tears and verse; noting, however, that Sir John moved him to pursue only “glory, and not sin.” 2 In the decades that followed Roe’s failed courtship, and the Hampton Court incident, and Roe’s death, Ben Jonson had much to say about Celia Boulstred; beginning, perhaps, with the “Celia” poems: Song: To Celia ˚ 3 Come, my Celia, let us prove, While we can, the sports of love. Time will not be ours forever – He at length our good will sever. Spend not then his gifts in vain. Suns that set may rise again, But if once we lose this light, ’Tis with us perpetual night. Why should we defer our joys? Fame and rumor are but toys. Cannot we delude the eyes Of a few poor household spies, Or his easier ears beguile, So removèd by our wile? ’Tis no sin love’s fruit to steal– But the sweet thefts to reveal. To be taken, to be seen, These have crimes accounted been. Song to Celia ˚ 4 Drink to me only with thine eyes, And I will pledge with mine; Or leave a kiss but in the cup And I’ll not look for wine. The thirst that from the soul doth rise Doth ask a drink divine; But might I of Jove’s nectar sup, 7 I would not change for thine. I sent thee late a rosy wreath, Not so much honoring thee As giving it a hope, that there It could not withered be. But thou thereon didst only breathe And sent’st it back to me; Since when it grows, and smells, I swear, Not of itself, but thee. Shall I not my Celia Bring? ˚ 5 6 Helen, did Homer never see Thy beauties, yet could write of thee? Did Sappho on her seven-tongued lute So speak (as yet, it is not mute!) Of Phaos’ form? Or doth the boy In whom Anacreon once did joy, Lie drawn to life in his soft verse, As he whom Maro did rehearse? Was Lesbia sung by learn’d Catullus, Or Delia’s Graces, by Tibullus? Doth Cynthia, in Propertius’ song, Shine more than she the stars among? /... / And shall not I my Celia bring, Where men may see whom I do sing? Though I, in working of my song Come short of all this learnèd throng, Yet sure my tunes will be the best, So much my subject drowns the rest. (1-12, 31-36) Jonson’s Celia poems may have been ghost-written for John Roe during his courtship of Boulstred; or written by Jonson in his own behalf after Roe’s departure; or written as a mock; or penned in praise of a woman whose name was not Celia. But given Boulstred’s prominence at Court as the only Celia in the Queen’s retinue, and given Jonson’s falling out with Lady Bedford and her Boulstred cousins, Jonson must have known that all three would poems be interpreted as tributes to Boulstred’s sex appeal. He was not quick to publish them. The first appears in Volpone (pub. 1607); the second, in The Forrest (1616). The third was found with Jonson’s papers after the poet’s death – together with other previously unpublished verse addressed to other women under their real names (Mary Wroth, Venetia Digby, Jane Pawlett, et al.) – and published in Underwood (1641). 1 Amico Probatissimo ] “D: Joanni Rowe Amico Probatissimo Hun Amorem et Delicias suas Satiricorum doctissimum PERSIUM cum doctissimo commentario sacravit Ben: Jonsonius et L.M.D.D. [= libens merito dono dedit]. Nec prior est mihi parens amico” [To John Rowe, his best-proved friend, Ben Jonson devotes this, his beloved and delight, Persius, of satirists the most learned, together with a most learned commentary; and gives the trifling prevsent as a gift: for me, a parent takes not rank before a friend]. 2 funeral ] £20, subsequently reimbursed, probably by Roe’s brother (Drummond, 18); Jonson, “27. On Sir John Roe.” Workes (1616), pp. 775-6. 3 glory, and not sin ] B. Song: To Celia ] ed. DWF from B. Jonson, Volpone 3.7 (Q1 1607, F1 1616), and The Forest (1616), no. 5. 4 Song to Celia ] ed. DWF from B. Jonson, The Forest (1616), no.9; Jonson, it has been noted, cribbed this entire lyric from Philostratus. 5 Shall I not my Celia Bring? ] ed. DWF from B. Jonson, Under-wood (1641), no. 46. 6 7 never see ] i.e., because Homer is reputed to have been blind. might I ] even if I could; change ] exchange the taste of your lips for the nectar of the gods. Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. 5 In Volpone, the eponymous scoundrel sings “Come, my Celia,” just moments before he attempts to rape her: this fictional Celia is the trophy wife of Corvino. Volpone’s intended victim has received scant sympathy from Jonson scholars. C.G. Thayer, for one, describes the Celia of Jonson’s Volpone as “an idiot, an eloquent Dame Pliant,” “a humorless, prim, fatuous girl without a brain in her head and nothing but clichés in her mouth” (52, 62). There is no compelling reason to suppose that Corvino’s bride represents Celia Boulstred, per se (for one thing, Jonson in 1607 was still hoping that Lucy Russell would resume her financial support). Nothing about Volpone or his retainers – a dwarf (Nano), a eunuch (Castrone), a hermaphrodite (Androgyno), and parasite (Mosca) – invites a reading of Volpone as one of Jonson’s many stage-satires on public personages. But Jonson in Volpone clearly wished to showcase his most admired love-lyric; and if it helped to make peace with Celia Boulstred and her wealthy cousin Lady Bedford now that Roe was out of the picture, so much the better. If it was Jonson’s hope that Volpone would restore him to favor, he was disappointed. Lucy Russell now favored Samuel Daniel as her court poet. Jonson represents himself as unbothered, by that: “Though she have a better verser got / (Or “poet,” in the court account), than I,” he sneered, Samuel Daniel “doth me, though I not him, envíe”). Nor was Shakespeare’s dramatic company – now, the King’s Men – eager to attempt another Jonson play after the 1603 failure of Sejanus. Unbothered by Shakespeare-envy, Jonson in 1605 collaborated with George Chapman and John Marston on Eastward Ho! – a comedy written for the Children of the Revels at the Blackfriars playhouse; which, instead of restoring Jonson’s credit at court, offended King James with its satire on the Scots and landed all three playwrights in prison. Condemned to have their ears and noses slit for the offense, Chapman, Marston, and Jonson were eventually pardoned; but not before Jonson’s “olde Mother” had prepared “a lustie strong poison” for her son and for herself, had the shameful punishment been carried out. That, at least, is how Jonson told the story to William Drummond, many years later. 1 The disgraces of longsuffering Ben Jonson were hardly permanent. He received a commission to write a court entertainment for May Day 1604, and a masque for the Christmas festivities of 1604/5. Released from prison in November 1605 following the Eastward Ho debacle, Jonson went on to produce some two dozen court masques in partnership with Inigo Jones, for which he was paid £40 each from the King’s exchequer (royalties comparable to a year’s wage for most London tradesmen). Celia Boulstred, meanwhile, had responded warmly to a lovesuit from Sir Thomas Roe, who adored her with an ardor unmatched by his late cousin, Sir John. Thomas and Celia might indeed have married, were it not that Boulstred in 1609 became gravely ill. Physicians at first diagnosed her stomach trouble as “the mother,” a.k.a. wandering womb – an imprecise medical diagnosis employed in the early modern period to cover ailments that were thought to attend upon feminine frailty. But no one, not even the doctors of the Medical College, could find a cure. By July, while in residence at Lucy Russell’s palace at Twickenham Park, Cecily Boulstred was said to be slowly wasting away, unable to hold down even small amounts of food or liquid. Hearing that Lady Lucy’s vivacious cousin and best friend had fallen ill, John Donne – one of several poets who still enjoyed the countess of Bedford’s generous matronage – requested and was granted a visit to Celia’s bedside. Donne found the patient in good temper, her pulse vigorous, her “understanding and voice” no more remiss (in Donne’s view) than usual. He concluded that her disease, though life-threatening, was hysterical. Writing the next day to his friend, Sir Henry Goodyere, Donne reports that Mistress Boulstred would not be not long for this world: Samuel Daniel, frontispiece of his Civil Wars (1609) 1 court poet ] It was to the countess of Bedford that Daniel dedicated the printed narrative of his Vision of the Twelve Goddesses (London, 1604); it is the longest epistle dedicatory in all of Jacobean drama; Though she…envie ] ed. DWF from Jonson, “Epistle to Elizabeth [Sidney,] Countess Of Rutland,” lines 69-70. The Forrest, in Workes (1616), 834; olde mother…poyson ] Drummond, 26. 6 • Women’s Works, vol. 3 • “I fear earnestly that Mistress Boulstred will not escape that sickness in which she labors at this time. I sent this morning to ask of her passage of this night; and the return is, that she is as I left her yesternight. And then – by the strength of her understanding and voice (proportionally to her fashion, which was ever remiss), by the evenness and life of her pulse, and by her temper – I could allow her long life, and impute all her sickness to her mind. But the history of her sickness makes me justly fear that she will scarce last so long as that you, when you receive this letter, may do her any good office in praying for her: for she hath not (for many days) received so much as a preserved barberry, but it returns; and all accompanied with a fever, the mother, and an extreme ill spleen.” 1 The anonymous author of A Closet for Ladies and Gentlewomen (1608) urges homeopathic remedies to calm the mother when it rises: “Take aqua-composita, and beat bayberries in powder, and put it into the aquacomposita, and put a spoonful or two in a draught of beer or ale, and so drink it”; or else, “Take rosen and beat it very fine, and put into salad oil and white wine and drink it, and it will do you good” (166-7, 178-9). When Ben Jonson heard of Boulstred’s illness, he was less gracious than Donne. Celia had recently dared to “censure” his wit. No express criticism of Jonson survives from Boulstred’s pen, nor is Jonson known to have published anything in the two years preceding that might have incurred her criticism; but Boulstred in the summer of 1609 had clearly heard about, and had evidently read in draft, Jonson’s Epicœne: the Silent Woman (whose debut performance at Court was not till Christmas); and she had dared to give the play two thumbs down. Jonson’s contempt for Cecily Boulstred from that moment forth took a dark turn toward character assassination, even as the young woman lay on her deathbed: On the Court Pucell ˚ DOES THE COURT PUCELL then so censure me, And thinks I dare not her? Let the world see: What though her chamber be the very pit Where fight the prime Cocks of the game, for wit? 2 And that as any are strook, her breath creates 3 New in their stead, out of the candidates? What though with tribade lust she force a Muse 4 And in an Epicœne fury can write News 5 Equal with that which for the best News goes – 1 I fear…spleen ] John Donne to Sir Henry Goodyer (n.d., July 1609?). 2 Pucell ] from French pucelle, maiden; but in English slang, prostitute (from which is derived the modern slang terms poozle [from 1578; later conflated with pussy, girl, from the 1560s]). Jonson here puns also on Cel Boulstred’s first name, and likens her to Joan de Pucelle, who in Elizabethan literature (as in Shakespeare’s 1 Henry VI) was typically depicted as deceitful and sexually promiscuous while parading as a virgin; Cocks ] specifically, John Cock, one of the writers of courtly “News”; with bawdy innuendo concerning the prime cocks alleged to be thriving in Celia Boulstred’s chamber and cockpit. 3 strook ] struck; And that ... candidates ] as one is struck down (i.e. in the fight, but also perhaps by venereal disease), she continually beckons new candidates with each breath. 4 Epicœne ] In Greek grammar, an epicene noun is one that without changing its gender may denote either sex. Jonson (followed by others) adopts the term to denote neither hermaphrodite nor androgyne per se, but a bisexual. The playwright adapted this otherwise unprecedented use of “epicene” from The Eagle and the Body (1609), a sermon by Bishop William Barlow; who observes that the Jacobean “Court, a full Bodie [for] the fatnesse and marrow wherof, hath fetcht many Eagles from all corners” – “eagles of the Epicene gender, both Hees, & Shees” – who with their “Satyricall Invectives, both in Pulpits and Pamphlets,” reduce the Court (or Church, or individual human) to “σκελετόν [skeleton], not σωµα [soma, body]; rather an Anatomie of Bones, then a Bodie of Substance” – so that they may cry with the prophet, “My leanness, my leanness!” (sig. B2). (Cf. Jonson’s 1624 masque, Neptune’s Triumph, where Jonson mocks “learned authors … of the Epicœne gender, Hees, and Shees,” a line copied directly from Barlow’s 1609 text.) Barlow’s Eagle and the Body, with its sexually indeterminate vultures feeding on the royal court, is the first recorded instance of Greek epicene being used metaphorically. In his caricature of Celia Boulstred’s “Epicene fury,” again in his figure of “Mistress Epicœne” (Master Morose’s boy-bride), Jonson reverses Bishop Barlow’s metaphor: he represents the eagle as the dominant male who snacks on bisexual prey. 5 tribade ] “A woman who engages in sexual activity with other women; a Lesbian” (OED); cf. Jonson’s Forest, no. 10: “Venus…with thy tribade trine, invent new sports”; from Greek τρίβειν, to rub; News ] Boulstred’s News of My Morning Work (below) is her only exemplar of the “court news” genre to have survived. Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. [25] [40] 7 As airy light, and as like “wit,” as those? What though she talk, and can at˚ once (with them) Make state, religion, bawdry, all a theme? And as lip-thirsty, in each word’s expense, Doth labor with the phrase more than the sense? What though she ride two mile on holy days To church, as others do to feasts and plays, 1 To show their ’tires, to view and to be viewed! What though she be with velvet gowns endued And spangled petticoats brought forth to th’ eye As new rewards of her old secrecy? What though she hath won, on trust (as many do), And that her “truster” fears her! Must I, too? I never stood for any place: my wit Thinks itself nought, though she should value it. 2 3 I am no statesman, and much less divine. For bawdry? —’tis her language and not mine. Farthest I am from the idolatry To stuffs and laces. Those, my man can buy. And “trust her” I would least, that hath forswore 4 In contract, twice. What, can she perjure more? Indeed, her dressing some man might delight: Her face, there’s none can like, by candle-light; (Not he, that should the body have, for case 5 To his poor instrument, now out of grace!). Shall I advise thee, Pucell? Steal away From court, while yet thy fame hath some small day. The wits will leave you, if they once perceive You cling to lords; and lords, if you leave them For sermoneers: of which, now one, now other, They say you weekly invite, with fits o’th’ mother, And practice for a miracle. Take heed! 6 This age will lend no faith to Darrell’s deed. Of if it would, the Court is the worst place, Both for the mothers and the babes of grace: For there, the wicked in the chair of scorn 7 Will call’t a “bastard,” when a prophet’s born. 1 ’tires ] attire, elegant outfit. 2 stood for any place ] applied for a position at Court; though she should ] even if she did (value my wit). 3 no statesman ] e.g., such as Sir Thomas Roe; much less divine ] 1. no god; 2. no clergyman, such as those who wait on Celia Boulstred’s sickbed. 4 in contract ] Jonson alleged that Boulstred has broken off two marital engagements (one to Sir John, the other to Sir Thomas Roe). 5 some man ] Cf. Epicœne 5.4, where Lady Haughty’s gentlewoman, Mistress Otter, remarks that a man has recently been tossed in a blanket at her house “for peeping in at the door”; instrument ] penis; out of grace ] Sir Thomas Roe, whose 1608 betrothal Boulstred is alleged to have broken; but perhaps with a glance at Jonson’s own “Celia” poems and fall from grace. 6 Sermoneers ] both Lucy Russell and Celia Boulstred supported Puritan clergy, a few of whom had evidently been brought to Celia’s bedside to pray for her recovery; Darrell ] John Darrell, Puritan exorcist and author of A True Narration of the Strange and Grievous Vexation by the Devil; Samuel Harsnet in 1603 exposed Rev. Darrell as a fraud who taught his accomplices to fake bewitchment and demon possession, thereby to secure convictions of suspected witches and to increase his own income as an exorcist. 7 a bastard ] i.e., if Boulstred remains at court, she will abandon her tribade lovers for a man, and become pregnant; and yet any verse, witticism, or infant, coming from Boulstred, will be despised as illegitimate. 8 • Women’s Works, vol. 3 • The venom in these lines is remarkable even for the always-irascible Ben Jonson. The poet’s scattershot accusations – that Boulstred is promiscuous in her speech and behavior, pretentious in her learning, a terror, an oath-breaker, a clothes-horse, a painted doll, a bisexual, a hypocrite, a hypochondriac, a likely candidate for unwed motherhood, and the object of derision – cohere only as a deeply personal assault on a young woman’s reputation. For twenty-first century readers, Jonson’s allegation that Celia Boulstred had a same-sex love interest, one that twice led to broken betrothals, is more likely to intrigue than to offend; but Jonson cannot have had much direct knowledge on the point of Boulstred’s sexual activity, either way. Nor can his other insults be reconciled with the report of those closest to her that Boulstred was a pious young woman who remained a virgin to her death and a devout Puritan. But when a desirable and successful woman has censured a poet, and dumped his best male buddy (Sir John), and disappointed another (Sir Thomas), one convenient means to salve the injury to masculine narcissism is for the dejected troubadour to proclaim the woman a tribade Lesbian. What is most surprising about Jonson’s caricature of Boulstred as a lust-driven bisexual is the innuendo concerning the Court Pucell’s significant other: courtiers and court-watchers could hardly have escaped making the inference that wealthy Lady Bedford – just a year older than Cel Boulstred and her constant companion – is the one who is alleged to have supplied Boulstred with an elegant wardrobe and other “new rewards of her old secrecy.” Jonson with his bitter diatribe invites his readers to see the ladies Boulstred and Russell as painted signs of Lesbian vice in Queen Anna’s own bedchamber, and he comes close to alleging that Cecily Boulstred is the countess of Bedford’s salaried same-sex prostitute. The countess of Bedford graciously performed in Jonson’s 1605 Masque of Blackness, his 1608 Masque of Beauty, and others; but Jonson was never able to nestle himself back under the wing of her financial patronage, and he had only himself to blame for that. Jonson’s denunciation of Cecily Boulstred was manifestly fueled by the poet’s outrage over her literary criticism. That the Court Pucell is said to be possessed of “an Epicœne fury” suggests not only that Celia swings both ways in bed, but that she was too vocal in her response to Jonson’s Epicœne, six months before its debut performance at Court. And if Jonson’s play, in draft, was anything like the finished product, then she, and Lady Bedford, and Dorothy Boulstred, had good cause to be critical. Epicœne is a misogynistic comedy in which the noise-hating Master Morose weds Mistress Epicœne, a silent woman, only to discover in the fifth act that he has married a handsome cross-dressed boy. Morose’s same-sex marriage is not, however, the primary object of the satire. In Epicœne Jonson targets the “collegiate” ladies at Court – three self-important, overdressed and well-painted women with intellectual pretensions: “Lady CEnTAUR” (a figure for CElia BULstred); “Doll” Mavis (Dorothy, who has “a worse face than she! you would not like this, by candle-light” [Epicœne 5.1; cf. “Pucell,” 32]); and “Lady Haughty,” president of the collegiates. Having forfeited Lucy Russell’s patronage by 1608, Jonson’s payback came in the figure of the “grave and youthful matron,” Lady Haughty: “no man can be admitted till she be ready, nowadays – till she has painted, and perfumed, and wash’d” (1.1). Not content with figuring Lady Bedford as Celia Boulstred’s Lesbian paramour, Jonson also represents her as a failed mother: Married now for almost fifteen years, the countess of Bedford had given birth only once (in 1602, to a son who died within a few weeks of birth). Jonson in Epicœne alleges a cause for that seeming infertility: Mistress Haughty proudly confesses that she and the other collegiates, to keep their youthful figures, use abortifacient herbs: 1 Morose. And have you those excellent receipts, madam, to keep yourselves from bearing of children? Haughty. O yes, Morose. How should we maintain our youth and beauty else? Many births of a woman make her old, as many crops make the earth barren. (Epicœne 4.3) 2 1 abortifacient herbs ] Jonson accuses Lady Bedford of birth-control aids that were commonly used throughout the Christian era and not criminalized until the early nineteenth century. Though condemned in patristic literature in the same breath and language with the sins of masturbation and non-horizontal marital sex, abortifacients were legal and freely available, and tolerated by Church authorities. The rare prosecution targeted suppliers, not the consumer. 2 receipts ] recipes. Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. 9 Reminded by Haughty of the approach of age, and shielded from pregnancy by abortifacients, Doll IT BECOMES a woman well at all times, and (Dorothy) advocates youthful fornication, since the chiefly in her child-bearing, and after her delivery, to have a care, as much as she can possibly, of the maiden who “excludes her lovers, may live to lie a preservation of her beauty: since there is nothing forsaken beldame, in a frozen bed.” that sooner decays and spoileth it than the oftenMistress Centaur muses, “who will wait on us to bearing of children. But as health is more precious coach, then? or write, or tell us the News, then? and recommendable than beauty, and seeing that a Make anagrams of our names, and invite us to the woman with child may be troubled and oppressed Cock-pit, and kiss our hands all the play-time, and with many accidents and infirmities during the nine draw their weapons for our honors?” months she bears her child, it will be therefore very “Not one,” replies Lady Haughty (4.3). necessary and profitable to seek out the means to Jonson imagines a remorseful future for Centaur free and deliver them thereof…. Oftentimes it happens to women that they cannot bear their burthen and Doll Mavis as decayed bachelorettes. But for to the time prefixed by nature, which is the ninth the moment, all three collegiates are content to month. This accident is called either a shift or slipwelcome, as a new member, Morose’s androgyping away; or else, abortment or (as our women nous bride, Mistress Epicœne: “We’ll have her to call it) a mischance. The shift is reckoned from the the college,” crows Haughty. And if “she have wit, first day the seed is retained in the womb till such she shall be one of us, shall she not, Centaur? time as it receiveth form and shape; in which time, We’ll make her a collegiate!” (3.6). if it chance to issue and flow forth, it is a shift. The Jonson’s avatar, Master True-wit, characterizes abortment happeneth after the fortieth day, yea, the “collegiate” as a woman who must “know all even to the end of the ninth month. For the abortment is a violent expulsion or exclusion of the the News, what was done at Salisbury, what at the child already formed and endued with life, before Bath, what at Court, what in progress; or so she the appointed time. But the sliding away, or shift, may censure poets and authors and styles, and is a flowing or issuing of the seed, out of the compare ’em – Daniel with Spenser, Jonson with womb, which is not yet either formed or endued the t’other youth, and so forth; or be thought cunwith life.… ning in controversies, or the very knots of divinity; Hippocrates is of opinion that women with and have often in her mouth the state of the queschild, in cases of necessity, may be purged from tion […] in religion, to one; in state, to another; in the fourth to the seventh month. But before and bawdry, to a third” (2.2). after those times he admits it not, nay, he forbids it directly; which, for all that, the physicians of our Sex-hungry Centaur is soon distracted by Motime observe not in cases of danger, because the rose’s friend, Sir Dauphine, who said to be “as fine medicines we use in these days (as rhubarb, manna, a gentleman of his inches, madam, as any is about cassia, and tamarinds) are not so violent as those the town.” Doll Mavis praises Dauphine (a figure that were used by our ancients (which were hellefor Sir Thomas Roe) as a man who “profess[es] bore, scammony, turbith, coloquintida, or the like). more neatness than a French hermaphrodite” and —Jacques Guillemeau wears “purer linen” than herself. Centaur desires Childbirth or, The Happy Delivery of Women. Dauphine as a man more handsome than others that Anon. trans. (1612), pp. 32, 69, 222. “have their faces set in a brake […] I could love a man,” she exclaims, “for such a nose! […] Good Morose, bring him to my chamber, first” (4.6). 1 The union of Morose with Mistress Epicœne, doomed from the start, comes unglued in Act 5: the promiscuous boy-bride is said to have had sex with Mr. Otter and with Mr. La-Foole as well as with Morose (whose marriage with Epicœne is now “post copulam” [5.3]); but Morose, like Gallimard in David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly, has not yet discovered that his wife is a boy. “Not taking pleasure in your tongue, which is a woman’s chiefest pleasure.” Morose seeks a divorce (2.3). He does so on a false pretense of his own impotence (an argument cited to justify the 1540 divorce of Henry VIII from Anne of Cleves, and which would be cited again, by the wife, in the notorious 1613 divorce of Frances Howard from the 2nd earl of Essex). Avaricious Epicœne refuses his consent to the proposed annulment. Haughty, Centaur, and Doll take pity on Epicœne. Just before the discovery of the boy-bride’s concealed sex, the three collegiates threaten to toss Morose in a blanket for his impudence, and to thrust him from court, together with Daw and La-Foole (5.4): 1 purer linen ] cleaner underwear (OED linen, n.3); brake ] bush; with bawdy innuendo. 10 • Women’s Works, vol. 3 • Haughty. Let ’em be cudgeled out of doors by our grooms! Centaur. I’ll lend you my footman. Doll. We’ll have our men blanket ’em i’the hall! […] I’ll ha’ the bridegroom blanketed, too! Centaur. Begin with him first! Haughty. Yes, by my troth. Morose. O, mankind generation! Forced to “give satisfaction by asking [their] public forgiveness,” Morose humbles himself before the female triumvir, a monstrous regimen of women: Morose. Ladies, I must crave all your pardons […] for a wrong I have done to your whole sex in marrying this fair and virtuous gentlewoman […] being guilty of an infirmity which, before I conferred with these learned men, I thought I might have concealed. The concealed “infirmity” of Master Morose is his (pretended) impotence, his excuse for annulment. The imperfectly concealed infirmity of Ben Jonson may that he fell in love, in 1600, with 19-year-old John Roe, now deceased; who fell in love with that poet-mocking, Lucy-loving, Puritan courtesan, Cecily Boulstred. ••• In the summer of 1609, while Jonson regaled his fellows at the Mermaid Inn with his libelous verses on Cel Boulstred, and perhaps with a draft of his new play, Epicœne, physicians at Lady Bedford’s Twickenham manor labored to save Boulstred’s life. A detailed narrative of her illness is supplied by Dr. Francis Anthony; who reports that he was summoned to Twickenham only after the combined expertise of the physicians in the College of Medicine despaired of success. Dr. Anthony that reports he was able to effect a cure with incremental doses of a pricey concoction called Aurum Potabile (Potable Gold). An Apology or Defense of a Medicine called Aurum Potabile (1616)˚ Part 2. Extreme Vomiting M ISTRESS CECILY BOULSTRED, a worthy gentlewoman and virgin, attending in near service our gracious Queen, in good favor and account, fell sick and had grievous passions; unto whom divers of the most famous physicians of the College [of Medicine] were called; who with great care and their utmost skill, sparing no cost (as was fitting in such a place) administered all kinds of conducing medicines, both cordials and other respectively, to the cause of her disease and passions: both such as be ready in the shops, as others by some singularity of art prepared. 1 Her passions still continued, if not increased: continual vomiting and rejection of whatsoever she took – meat, drink, medicines – with swoonings, torture, torments of every part of her body, a miserable and pitiful spectacle, much lamented of many very honorable persons. She could not rest nor sleep, night or day; so that, sinking under the burden of this affliction, with the violence and continuance thereof, her strength utterly failed. She could not retain so much as one drop of any broth or other nourishment. Her stomach, by conjecture of all physicians, was drawn together and shut up, without any power or faculty to perform the offices of nature. In this miserable estate, this distressed gentlewoman languished two whole months without any ease or relief by the use of any [of] the medicines given her by the advice of the said physicians – all things, tending to a more desperate and immedicable estate. Whereupon the mother of this gentlewoman demanded of these said doctors whether they had any hope to give help (or at leastwise, ease) to her daughter: “Else” (she said), she “would send for Doctor Anthony.” Those doctors hereupon limited themselves to a certain time which they spent in their uttermost abilities to perform, to the intent I should not be called; to which purpose, they commanded an apothecary to attend in the chamber of the patient all the next day and night; and every third hour, to give her a cordial. Then voluntarily they said to the mother, “Send for Doctor Anthony if you will, and God send him good success with your daughter.” Then I was sent for. And finding this gentlewoman in so desperate a case, left and given over by all the doctors of the College as not to be recovered (for besides the advice of these six, there had been public consultations in the College as is requisite in such-like cases, which seldom come in use), I desired God to bless my endeavors, and to continue His blessings in the administration of this, my happy medicine. 1 passions ] sufferings; conducing medicines ] serviceable; cordials ] stimulating or restorative medicines. Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. 11 After a small time, upon due and mature consideration of all things, I gave her at the first, not a whole spoonful of my Aurum Potabile, as in other cases, but much less, scarce a quarter so much; which she cast up again with a vehement force and torture of her body. A little while after, I gave her as much more – which she cast up in the same manner as she did the first. Again I gave it the third time, some part of which she also cast up, but kept some, with a kind of strife or conflict between the medicine and the malady. Then I advised that she should not further be troubled for a season, but to try if she could now take a little rest or sleep. So she disposed herself thereunto and slept soundly a whole hour; which divers of great account then present can witness. For she snored (that we all heard), which seemed strange to all, considering for a long time before, she had taken no rest. When she waked, she said that she found herself somewhat better at ease. Then (which was the fourth time) I gave her half a spoonful, which she kept without any contending or trouble to her body. This gave me (and many worthy gentlewomen there present) great hope of a good recovery – wherein (God be praised!) we were not deceived. For in all the other administering of this medicine (orderly, as she was able to bear, increasing the quantity), her spirits were relieved! She daily recovered strength. All the passions, symptoms, and accidents of her diseases ceased. Her sickness fully left her, and she recovered perfect health! Thus, with the use of this happy medicine, this gentlewoman was recovered, and cured of that dangerous disease wherein those other doctors had wearied themselves, and forsaken her – at which her friends wondered, mine rejoiced, and other malicious adversaries fretted (for which, God be praised!). If they will call these effects of “juggling” and of “a corrosive medicine,” they will hardly find any “cordial” amongst all their dispensatories and magistral prescriptions: the cause, and effect, are essential relatives! ••• Dr. Anthony published his case study (in Latin and English) in 1616, seven years after he gave those doses of Aurum Potabile to Celia Boulstred. Extra copies of his title page were printed off for use as advertising bills. But in point of fact, Dr. Anthony’s juggling was less miraculous than he remembers: within days of his first visit to the patient’s bedside, Celia Boulstred was dead. The patient’s brother-inlaw, James Whitlocke, reports: “Cecil Boulstred, my wife’s sister, gentlewoman to Queen Anna, ordinary of her bedchamber, died at Twick’n’am in Middlesex, the earl of Bedford’s house, 4 August 1609.” 1 The local parish register indicates that she was buried on August 6th. The cause of death may have been a brain tumor (which can cause persistent, unexplained, vomiting without nausea); or gastric cancer. Cecily Boulstred, though already ill when Jonson penned “The Court Pucell,” lived long enough to read it. As Jonson a decade later told the story of his masterpiece, the paper on which it was written “was stolen out of his pocket by a gentleman,” possibly George Garrard, “who drank him drowsy, and given Mistress Boulstred; which brought him great displeasure” (Drummond, 54). Jonson thereby suffered the “great displeasure,” not only of Cel Boulstred but of his former benefactor, Lucy Russell. On his 1618-19 tour of Scotland, Jonson happened to have his libel on Cecily Boulstred back where he wanted it: in his pocket. Visiting with William Drummond in Edinburgh over the Christmas holidays, the poet read “The Court Pucell” aloud for his host’s amusement. That Drummond was unimpressed may be inferred from Jonson’s self-justification immediately after: defending his “Pucell’ as merely representative of universal lechery, Jonson told Drummond that “there was no abuses to write a satire of” – and in which he repeateth – “all the abuses in England and the world” (Drummond, 10). Following the visit, Drummond expressed his censure in remarks not intended for publication. Ben Jonson, he wrote, “is a great lover and praiser of himself, a contemner and scorner of others; given rather to lose a friend than a jest; jealous of every word and action of those about him (especially after drink, which is one of the elements in which he liveth); a dissembler of ill parts which reign in him, a bragger of some good that he wanteth; thinketh nothing well but what either he himself, or some of his friends and countrymen, hath said or done. He is passionately kind and angry (careless either to gain, or keep); vindictive – but, if he be well answered, at himself” (Drummond, 56). 1 Cecil…1609 ] Ed. DWF from Whitlocke, Liber Famelicus, 18; As a coincidental point of interest: on 13 August 1609 (a week after Boulstred’s burial), Henry Cary, wife of Elizabeth Tanfield Cary, wrote Dr. Anthony from Barkhamsted, ordering fresh quantities of aurum potabile; with a glowing testimonial; Cary wrote again on 31 August to say that the drug since his last letter had healed a servant of paralysis, and his own infant daughter of the measles (Katherine Cary, then three months old). In 1616, Dr. Anthony reports that aurum potabile also healed Lucius, the Carys’ eldest son, of the smallpox (1610, pp. 54-55; 1616, p. 87). 12 • Women’s Works, vol. 3 • COURT POETS soon after the death of Cecily Boulstred weighed in with their memorial tributes. Among them is an “Epitaphium” by Sir Edward Herbert, a friend of Ben Jonson and of Celia’s forlorn lovers, Sir Thomas Roe and the late Sir John Roe. In his Latin subtitle, which the ladies could not read, Herbert insinuates that Cecily Boulstred perished of an unquiet conscience; and yet, the English text of Herbert’s poem reconfigures the maiden’s mutinous “powers” as religious “zeal.” Herbert affirms that Boulstred during her starvation (“Her fasts”), overcame excess; barred all access to sin; withstood the long siege of Death; and finally surrendered the fortress of her virgin flesh to the grave, even as her spirit found refuge in Heaven: Sir Edward Herbert, by Isaac Oliver Epitaph. Caecil. Boulser ˚ quae post langue scentem morbum non sine inquietudine spiritus & conscientiae obiit ˚ METHINKS Death like one laughing lies, Showing his teeth, shutting his eyes, Only thus to have found her here He did with so much reason fear, And she despise. 1 2 For barring all the gates of sin Death’s open ways to enter in, She was with a strict siege beset, To what by force he could not get, By time, to win. This mighty Warrior was deceivèd yet, For what he mutine in her powers thought Was but their zeal, And what, by their excess, might have been wrought, 3 Her fasts did heal— Till that her noble soul, by these, as wings, Transcending the low pitch of earthly things, As being relieved by God and set at large, And grown, by this, worthy a higher charge, Triumphing over Death, to Heaven fled— And did not die, but left her body dead. One-upping Sir Edward Herbert, John Donne composed two elegies in memory of Lady Bedford’s deceased favorite. In the first, “Death, I recant” (74 lines), Donne censures Death as an all-consuming glutton who swallows the good with the wicked, a monster who has now audaciously swallowed down Cecily Boulstred, though she was a maiden “proof ’gainst sins of youth,” whose “virtues did outgo / Her 1 Epitaph…obiit ] “Epitaph on Cecily Boulstred who died young, languishing with an unquiet spirit and conscience.” 2 found … fear ] laughingly found here, dead, a woman who despised Death and whom Death once had cause to fear. 3 this mighty Warrior ] Death; mutine ] a mutiny (What Death mistook for a rebellious spirit was in fact religious zeal); their excess ] the excessive use of “her powers” (beauty, wit, etc.); her fasts ] her illness starved her to death. Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. 13 years.” Seeking figurative compensation for the loss of that devoured feminine morsel, Donne invokes the specter of libels and gossip that might have dogged the heels such a good woman as Celia, had she lived on as a sociable virgin in the Jacobean court: Elegy on Mistress Boulstred ˚ John Donne […] Had she perséver’d just, there would have been Some that would sin, mis-thinking she did sin: Such as would call her friendship, love, and fain To sociableness a name profane; Or sin by tempting, or (not daring that) By wishing, though they never told her what […] 1 Politely disingenuous is the poet’s speculation that Boulstred, had she survived, might have seen her sociability misrepresented as profane solicitation, her openness as promiscuity. Donne has in mind a particular instance: his reference is to that 1602 libel, in which a poet (thought to be John Roe) had accused a too-sociable Cecily Boulstred of having offered up illicit “love” in place of “friendship.” Donne’s elegy recuperates the reputation of his patron’s deceased friend while excusing Roe’s “To Mistress Boulstred” as a poem that arose from a simple misreading of her feminine nature. Donne’s recuperative spin thereby ensures Lucy Bedford’s favor without transgressing the buddy system. In a second elegy on Boulstred, “Language, thou art too narrow” (62 lines), Donne applies his hyperboles with a spatula, advising Death to take early retirement. Now that glutton Death has abducted Cel Boulstred, the sting of human mortality has vanquished the entire planet: John Donne National Portrait Gallery Elegy XI ˚ John Donne […] if we be thy conquest, Thou’ast lost thy end – for in her, perish all. Of if we live, we live but to rebel: They know her better now, that knew her well. If we should vapor out, and pine, and die (Since she first went), that were not misery. She changed our world, with hers. Now she is gone, Mirth and prosperity is oppression: For of all moral virtues, she was all The Ethics speak of “virtues cardinal.” Her soul was Paradise: the Cherubin Set to keep it, was Grace, that kept out sin […] With two elegies by John Donne to her credit, Cecily Boulstred might well have been permitted to rest in peace as the deceased epitome of all moral virtues. But Ben Jonson was not yet done with her. On news of her decease, Donne’s rival, Ben Jonson, hastily revised his verdict on Celia’s character. In a poem titled, simply, “Epitaph,” he praises Boulstred as the court’s singular model of chastity. Perhaps Jonson regretted the extreme nastiness of his “Court Pucell.” More certainly, the “Epitaph” that he wrote on the news of Boulstred’s death represents a cynical move to recover his lost patronage and his standing at court now that Cecily Boulstred and her dramatic criticism no longer stood between him and the countess of Bedford: 1 fain ] ascribe (as presumption). 14 • Women’s Works, vol. 3 • Epitaph ˚ Ben Jonson STAY, view this stone. And if thou be’st not such, Read here a little, that thou may’st know much: It covers, first, a virgin; and then one 1 Who durst be that in Court, a virtue alone To fill an epitaph. But she had more: She might have claimed to have made the Graces, four; Taught Pallas, language; Cynthia, modesty. As fit to have increased the harmony Of spheres, as light of stars: she was Earth’s eye, The sole religious house and votary, Not bound by rites, but conscience. Wouldst thou all? She was Sell Boulstred! – in which name I call Up so much truth, as could I it pursue, Might make the Fable of Good Women, true. Informed by George Garrard that “greater wits have gone before” in their praise of Boulstred, Jonson sent him a copy of his “Epitaph” and forwarded a copy to the Countess of Bedford, possibly hoping that his epitaph would be chosen to grace Boulstred’s tomb (it wasn’t). But as if to clarify his intentions and to disambiguate his own eulogy, Jonson with his copy for Garrard included a cover note stating that the news of Celia’s death has made him “a heavy man” (perhaps literally: Jonson in middle age grew obese, pushing almost 300 lbs.). Jonson remarks further to Garrard that he wishes he had seen Celia before she died – so that others, “that live, might have corrected some prejudices they have had injuriously of me.” 2 But if Jonson in his posthumous praise of Boulstred was seeking to repair his relations with a moneyed matron, he seems unable to resist, even here, the temptation to equivocate in his praise of Cecily Boulstred: her tombstone covers one that was “first, a virgin” (as what woman is not, chronologically speaking?); and she dared to be so at Court (where chastity, Jonson implies, is universal sham). “She might have claimed” to be gracious and witty. She might have claimed to teach modesty to Cynthia (Elizabeth I), and she might have claimed to have taught intelligible English to Pallas (Queen Anna). Jonson might, therefore, make credible Chaucer’s “fable” of good women. But in the end, Jonson modestly excuses himself from that hypothetical challenge. He settles for calling up “so much truth” in Cecily’s name: “Wouldst thou all? / She was Sell Boulstred” (spelled thus, both in Jonson’s manuscript and printed text). ••• Celia Boulstred, Maiden of the Bedchamber: News THE “NEWS” that Lady Centaur speaks of in Epicœne 4.3 refers to the literary game of writing moral or satirical news headlines, a genre that flourished at court c. 1605-1610. Extant examples include “News from Court” by Sir Thomas Overbury; “News from Sea,” by William Strachey; “Country News” by Sir Thomas Roe; “News from the Very Country,” by John Donne; “Answer to the Very Country News,” by Lady Anne Southwell; and “News of my Morning Work,” by Cel Boulstred. Written probably in 1609, Boulstred’s one surviving News article was destined to receive a second life, not in manuscript this time, but print, for the whole world to read. In his 1613 poem, A Wife, Sir Thomas Overbury had catalogued the feminine virtues that he deemed essential in marriage, none of which he could see manifest in Frances (Howard) Devereux, the vixen to whom his sometime friend, Robert Carr, had betrothed himself. Resenting the interference with her love-life, Lady Frances first contrived to have Overbury imprisoned in the Tower of London, where she poisoned him. In 1615, when it was discovered that Overbury’s untimely death was in fact a murder, Sir Thomas Overbury his Wife became an instant bestseller, augmented by various courtly “News” items, previously unpublished; one of which was Cecily Boulstred’s “News of my Morning Work”: 1 Who durst be that in Court? ] Cf. John Roe: “Good wit never despair’d,” at Court, or “Ah me!” said— / For never wench at court was ravishèd” (The witty wooer is never unrequited, nor is rape possible, at Court, a milieu in which no woman ever says “No” to sex – or at least, not if the price is right). J. Roe, “Love and Wit,” lines 15-16. 2 a heavy man…injuriously of me ] B. Jonson to G. Garrard (Aug. 1609), Houghton Lib. MS JnB102, ed. DWF. Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. 15 News of My Morning Work ˚ THAT to be good, the way is to be most alone—or the best accompanied. That the way to Heaven is mistaken for the most melancholy walk. That the most fear the world’s opinion more than God’s displeasure. That a Court-friend seldom goes further than the first degree of charity. That the Devil is the perfectest courtier. That Innocency was first cousin to man; now Guiltiness hath the nearest alliance. 1 That Sleep is Death’s ledger ambassador. That time can never be “spent”: we pass by it and cannot return. That none can be sure of more time than an instant. That Sin makes work – for Repentance, or the Devil. That Patience hath more power than Afflictions. That everyone’s memory is divided into two parts: the part losing all is the sea; the keeping part is land. That Honesty in the court lives in persecution, like Protestants in Spain. 2 That Predestination and Constancy are alike uncertain to be judged of. 3 That Reason makes Love the serving-man. That Virtue’s favor is better than a King’s favorite. That being sick begins a suit to God; being well, possesseth it. 4 That health is the coach which carries to Heaven; sickness, the posthorse. That worldly delights, to one in extreme sickness, is like a high candle to a blind man. That absence doth sharpen love, presence strengthens it; that the one brings fuel, the other blows it till it burns clear. 5 That love often breaks friendship, that ever increaseth love. That constancy of women, and love in men, is alike rare. That Art is Truth’s juggler. That Falsehood plays a larger part in the world than Truth. That blind Zeal and lame Knowledge are alike apt to ill. 6 That Fortune is humblest where most contemned. That no porter but Resolution keeps Fear out of minds. 7 That the face of Goodness without a body is the worst wickedness. That women’s fortunes aspire but by other’s powers. That a man with a female wit is the worst hermaphrodite. That a man not worthy being a friend, wrongs himself by being in acquaintance. That the worst part of ignorance is making good and ill seem alike. That all this is “news” only to fools. —Mistress B. Jonson’s verbal fusillade may perhaps have been triggered by Boulstred’s remark “That a man with a female wit is the worst hermaphrodite”: Jonson had a career-long interest in hermaphroditism, a preoccupation which by 1609 was already exhibited in Cynthia’s Revels, Volpone, and Epicœne. But “News of my Morning Work” was not Boulstred’s only utterance before she died nor is Jonson the only poet whose plays may have met with Celia’s criticism. In an epigram addressed to John Fletcher, Jonson laments that Fletcher’s 1608/9 play, The Faithful Shepherdess, failed to please, having fallen victim to unnamed critics who sit in judgment upon “the life and death of plays,” whether “knight, knight’s man, / 1 ledger ambassador ] resident or ordinary ambassador. 2 Predestination and Constancy ] whether God has predestined your soul for Heaven or Hell, and whether or not your lover is faithful, are questions that leave room for anxious doubt. 3 That reason... Serving-man ] The reasonable person is not mastered by passion but makes love subject to reason. 4 posthorse ] postal horse; health… sickness ] Spiritual health gets you to Heaven; sickness takes you there. That love ... Love ] (Romantic) love has ruined many friendships; but friendship strengthens a love-relationship. 5 6 7 fortune ... contemned ] A turn of Fortune cannot harm one whose happiness does not depend on her favor. face ] appearance. 16 • Women’s Works, vol. 3 • Lady or Pucell that wears mask or fan, / Velvet or taffeta cap, ranked in the dark / With the shop’s foremen.” 1 That Jonson’s resentment of Boulstred arose from a single sentence is doubtful; what angered him is that a pucell of the royal court, a maiden of the bedchamber close to Queen Anna and to Lady Bedford, could exercise the virtual powers of a Lord Chamberlain, presuming to applaud or hiss, to approve or damn, works of masculine genius by artists in need of Lucy Russell’s matronage. Cel Boulstred and her courtly “News” were now featured in one of the most widely read volumes of the seventeenth century. (By 1664, Overbury’s Wife would pass through more editions than all of Jonson’s plays and poems put together.) And despite Jonson’s professed imperturbability, Boulstred’s critical voice, if not that particular remark, fanned the embers of the playwright’s malice. Within weeks of the posthumous 1614 publication of Boulstred’s “News,” Jonson took another swipe at the dead maiden’s sexual reputation, this time in Bartholomew Fair (1614), in the figure of Alice of Turnbull, alice being an anagram of Celia, and Turnbull being another play on Bullstred: this time, the late Maiden of the Bedchamber is figured as a young prostitute who complains that “poor common whores can ha’ no traffic, for the privy rich ones” (like Lady Bedford) who “lick the fat from us” (4.5). In his conversations with William Drummond (Jan. 1618/9) – four years after Boulstred’s “News” and Jonson’s own Bartholomew Fair – we find the playwright still gloating over his poetical revenge on the court pucell, Cel Boulstred. A decade later he was still harping on the same string, this time in in The New Inn, a second play in which a morose protagonist competes with high-society strumpets for the love of a cross-dressed boy. The 1629 play does not invite viewers to see Jonson and Roe in the figures of Lovell and Frank, as the 1609 play does in the persons of Morose and his boy-bride. But the women of the Court are represented much as they were in Epicœne, and deliberately so: it is in The New Inn that Jonson recycles his 1602 libel, “An Elegy to Mistress Boulstred.” The doctrine that a poet who immortalizes a woman in verse has also the right to mortify her reputation was a catechism adopted by the “Sons of Ben” – a brotherhood of Cavalier poets who looked to Jonson as their chief mentor. Thomas Carew for one, after writing an elegy in praise of Jonson’s New Inn, penned his own compendium of Celia poems in which he out-Jonson’s Jonson’s famous Celia lyrics. Carew’s “Celia” (possibly Mary Villiers, daughter of the first duke of Buckingham) failed to give the poet what he wanted in exchange for his praise, whether sex or financial support; whereupon Carew reminded her, and his wider readership, that he might easily re-create his goddess as a pucell: Ingrateful Beauty Threatened ˚ KNOW, CELIA, since thou art so proud, ’Twas I that gave thee thy renown: Thou hadst in the forgotten crowd Of common beauties lived unknown, Had not my verse extolled thy name, And with it imped the wings of Fame. That “killing power” is none of thine: I gave it to thy voice and eyes; Thy sweets, thy graces, all are mine; Thou art my star, shin’st in my skies. Then dart not from thy borrowed sphere Lightning on him that fixed thee there. Tempt me with such affrights no more, Lest what I made, I uncreate […] Ben Jonson died in 1637. When his ungathered poems were collected for publication, his 1609 epitaph on Cecily Boulstred was not found; but the playwright had saved a copy of the Pucell libel, subsequently printed in Underwood. Jonson’s “Court “Pucell” and the misattributed “Elegy to Mistress Boulstred” became the principal texts by which the notorious “Sell Bulstrode” has been known and remembered ever since. 1 life and death…foremen ] “To Mr. John Fletcher,” ed. DWF from Faithful Shepherdess” (acted 1608, pub. 1609); Velvet or taffeta cap ] 1. a cap of either velvet or taffeta; 2. velvet patches (to cover venereal sores) or a taffeta cap. Extract from Women’s Works, vol. 3 (1603-1625), © 2013. Royalties support EQUALITY NOW. 17 An effective antidote to Jonson’s poison-pen comes neither from the equivocal “Epitaph,” nor from John Donne nor from Edward Herbert, nor even from Lucy Russell, but from Sir Thomas Roe, who loved Cecily Boulstred and remembered her as the sum of human perfection. In October 1614 (this was five years after Boulstred’s death), the East India Company appointed Thomas Roe to be Britain’s first ambassador to the court of the emperor Jangir in Mughal India. Knowing that he might never return but hoping to produce an heir, Roe on December 15th married Lady Eleanor Beeston, a nineteen-year-old widow of independent means. Seven weeks later, Roe embarked for the East, taking with him, as his most cherished possession, a miniature watercolor portrait of the late and well-beloved Cecily Boulstred. Roe and his English entourage reached the anchorage off Surat on 18 September. There ensued a long overland trip north to Ajmir, during which Roe became gravely ill, arriving at Jahangir’s palace in December, carried in a palkhi. In January 1616 Roe at last presented his credentials to the emperor, together with many gifts that included a lavish English coach. During his three-year sojourn in the East, Roe became Jahangir’s drinking partner and favorite European. Roe’s shrewd diplomacy marked the beginning of England’s influence in the sub-continent. On 2 September 1616, his birthday, Emperor Jahangir partied hardy, with feasting, drinking, dancing nautch girls, and processions of bejeweled elephants. About ten o’clock that night, with plenty of wine still remaining, his Majesty summoned the English ambassador from bed. Roe reports: “He had heard I had a picture which I had not showed him, [the emperor] desiring me to come to him, and bring it; and if I would not give it him, yet that he might see it and take copies for his wives. I rose and carried it with me.” Jahangir collected European art. In the hall of audience were now displayed portraits of King James and Queen Anna; of their daughter, Princess Elizabeth; Frances Howard, countess of Somerset; Sir Thomas Smythe, governor of the East-India Company; “a Citizen’s wife of London”; and paintings of Christian saints. The one picture that Roe had not yet exhibited at the court of Ajmir was his private treasure: his water-color miniature of Cecilia Boulstred. Thinking on his feet, Roe before leaving his quarters that night removed from the wall a French painting, oil on canvas, that had been brought from England. He carried both works of art to the palace. “When I came, I found [his Majesty] sitting cross-legged on a little throne, all clad in diamonds, pearls, and rubies; before him, a table of gold; on it, about fifty pieces of gold plate set all with stone, some very great and extremely rich, some of less value, but all of them almost covered with small stones; his nobility about him in their best equipage, whom he commanded to drink frolicly (several wines standing by in great flagons). ”When I came near him, he asked for the picture. I showed him two. He seemed astonished at one of them – and demanded whose it was. “I answered, a friend of mine that was dead. He asked me if I would give it him. “I replied that I esteemed it more than anything I possessed, because it was the image of one that I loved dearly and could never recover; but that if his Majesty would pardon me my fancy and accept of the other, which was a French picture but excellent work, I would most willingly give it him. “He sent me thanks, but that it was that only picture he desired, and loved as well as I; and that if I would give it him, he would better esteem of it than the richest jewel in his house. […] He confessed he never saw so much art, so much beauty – and conjured me to tell him truly whether ever such a woman lived. I assured him there did one live, that this [picture] did resemble in all things but [her] perfection, and was now dead.” […] 1 1 He sent me…now dead ] Ed. DWF from Roe (ed. 1899), 1.253-6. In the end, Jahangir “replied he would not take it – that he loved me the better for loving the remembrance of my friend, and knew what an injury it was to take it from me. By no means he would not keep it but only take copies (and with his own hand he would return it), and his wives should wear them. (For indeed, in that art of limning, his painters work miracles).” Portrait: identified woman, thought to be Cecilia Boulstred, dressed as Flora, goddess of flowers, c.1609, by Isaac Oliver.