Print Layout 1 - Moultrie Middle School

advertisement

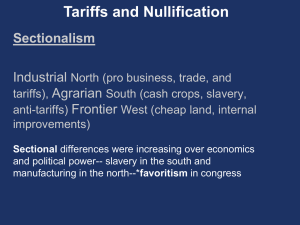

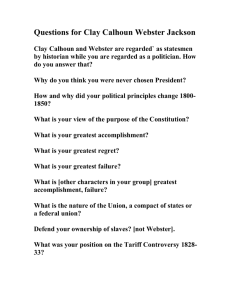

chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:27 PM Page 169 chapterfifteen SOUTH CAROLINA ON THE DEFENSIVE IN THE AGE OF JACKSON Why did the Age of Jackson put South Carolina on the defensive? SELECTED VOCABULARY Jacksonian Democracy Democratic Party Spoils system Veto Whig Party Arsenal Nullification OVERVIEW In 1828, Andrew Jackson was elected president. It was the era of Jacksonian democracy, when more and more leaders were chosen by popular vote. The old Republican Party split into factions. They were the Democratic Party of Jackson and the Whig Party. John C. Calhoun emerged as a national figure. The people of South Carolina were very upset. The economy was unsteady. The Denmark Vesey insurrection disturbed the whites. The state was divided over the tariff and nullification. This statue by Anna Hyatt Huntington portrays Andrew Jackson as a young man in the Waxhaws where he grew up. It is in Andrew Jackson State Park in Lancaster County. A copy stands on the campus of Columbia College. S.C. Department of PRT Who was the only president who claimed he was born in South Carolina? chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:27 PM Page 170 TIMELINE UNITED STATES SOUTH CAROLINA 1822 Denmark Vesey Insurrection 1824 Disputed presidential election, J. Q. Adams elected 1828 Andrew Jackson elected president Tariff of 1828 1824 John C. Calhoun, vice president, until 1832 1828 S. C. Exposition and Protest 1830 Webster-Hayne debate 1831 Fort Hill Letter 1832 Jackson vetoed Bank bill Whig Party began to form 1832 Nullification Convention 1833 Tariff of 1833 I. JACKSONIAN DEMOCRACY What was Jacksonian Democracy? The president who shaped American politics more than any other between Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln was Andrew Jackson. He is also the only president who claimed South Carolina as the state of his birth. The Age of Jackson was the era when American politics for the first time was based on the ideal that all men (that is, all white males) were politically equal in spite of wealth, family, or education. The role of government, as Jackson understood it, was to make sure that no group had more privileges than any other. More and more, political leaders were chosen by popular vote and, therefore, appealed to the masses. For the first time candidates for office held campaign rallies, barbecues, and torchlight parades to ask vast crowds to vote for them. The older, gentlemen politicians were swept aside in the new popular elections. By 1824 the Federalist Party was dead. The Republican Party had split into factions. That year the state legislatures nominated their favorite sons for president. In the election Andrew Jackson received the largest number of popular and electoral votes, but not a clear majority. So the House of Representatives voted, and John Quincy Adams became president. John C. Calhoun was unopposed for vice president. Adams was not a popular leader, and Jackson began his campaign for the 1828 election as soon as Adams was in the White House. II. JACKSON AND THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY What role did Jackson play in developing the Democratic Party? Jackson’s fame rested on his victory over the British at New Orleans in 1815. Born in the Waxhaws in 1767, he was put in jail by the British in Camden during the Revolution. Later he read law in North Carolina. He moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he became a wealthy lawyer and planter. He owned over 100 slaves. To his followers he was a self-made man of the frontier in an age of rapid change. He molded the old Republican Party into a vast political machine called the National Democratic Party. It included urban workers and immigrants, Western businessmen, Southern planters, and Northern bankers and industrialists. In 1828, Jackson soundly defeated Adams, and he was reelected four years later. For thirty years, from 170 | Chapter 15 chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:27 PM Page 171 1828 to 1859, the Democratic Party, which Jackson created, won the presidency in every election but two. Once in the White House, Jackson had no program, but he knew how to keep power. He used the spoils system in which he replaced federal office holders with persons loyal to him. He began the national party convention to choose popular candidates for president. He paid little attention to his cabinet, but he formed a group of his friends into the Kitchen Cabinet. He kept control of Congress by using his influence with Democratic senators and representatives. When Congress passed laws he did not like, he freely vetoed them. III. THE RISE OF THE WHIG PARTY Who were the Whigs? In 1832, President Jackson vetoed the bill to renew the charter of the Second Bank of the United States. He said the bank did not favor all the people: “It made the rich richer and the potent more powerful.” Three of the greatest senators in American history were in Congress. They were John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster. They began to form a new party to oppose Jackson. At first they called it the Democratic Whig Party. Later it became the Whig Party. Like the Democrats, they appealed to a large number of Americans, usually the more wealthy classes. On the whole, they believed that the government ought to promote economic growth in the nation. The Whig Party always had trouble finding a popular candidate for president. Webster, Clay, and Calhoun wanted to be president, but they were not national candidates. They appealed to their own sections. Only twice did the Whigs win the White House. In 1840 they successfully ran William Henry Harrison of Ohio and John Tyler of Virginia. Both were Virginia-born planters, but Harrison ran as a man of the frontier who lived in a log cabin. He was a military hero who had defeated the Shawnee leader, Tecumseh, on the Tippecanoe River in Indiana. Harrison had the first campaign slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” In 1848 the Whigs chose Zachary Taylor, the hero of the Mexican War. Until the eve of the Civil War, the Whigs gave the country a strong two-party system. Andrew Jackson became a national hero in the Battle of New Orleans. He became the seventeenth president of the United States. U.S. Senate What was the Age of Jackson? IV. SOUTH CAROLINA ON THE DEFENSIVE What were two reasons why South Carolina was on the defensive after 1828? In 1828, South Carolinians were thrilled with the election of Andrew Jackson as president. A native son was in the White House, and John C. Calhoun was Henry Clay was one of the greatest senators in American history. He was one of the founders of the Whig Party. U.S. Senate What did the Whigs believe? SC on Defensive | 171 chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:27 PM Page 172 elected to a second term as vice president. South Carolinians led the nation. But the state was in trouble. Its economy had not grown after the Panic of 1819 like the rest of the nation. The debates over Missouri showed how strong the sentiment against slavery was in the North and the Northwest. V. THE DENMARK VESEY INSURRECTION What was the Denmark Vesey Plot, and how did it affect South Carolina? This painting of Denmark Vesey shows him leading a class meeting in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. It hangs in Gaillard Auditorium in Charleston. Why do you suppose the artist did not show Vesey’s face? 172 | Chapter 15 The census of 1790 indicated that for the first time since about 1705 South Carolina had a majority of whites, not blacks. But with the invention of the cotton gin and the reopening of the slave trade, the black population grew rapidly. With new cotton lands available in Alabama and Mississippi, whites began to move into the Old Southwest. In 1820 the census showed that the state had a black majority once again. Blacks were 52.8 percent of the population. By 1860 they were 58.6 percent of the state’s people. Since the Stono Rebellion in 1739, white South Carolinians had been fearful of a slave revolt. In 1791 slaves in Santo Domingo had a successful revolt. White planters from the West Indies poured into Charleston. They told stories of murder and burning. Governor Charles Pinckney wrote to the Santo Domingo Assembly: “A day may arrive when [we] may be exposed to the same insurrection [;] we cannot but sensibly feel for your situation.” Since the Revolution there had been a small number of people in the state who believed strongly in the abolition of slavery. Henry Laurens was one of that group. The few Quaker meetings also believed in abolition. The Methodists openly preached against slavery. According to church law, no Methodist could own slaves and be a member in good standing. In 1795 the preachers in the state signed a pledge never to own slaves. The white aristocracy in Charleston threw rocks at the Methodist meeting house and mobbed the preachers because of their views. There were a number of efforts by slaves to free themselves from bondage. There was one in Columbia in 1805 and in Ashepoo and Camden in 1816. The largest revolt was organized by Denmark Vesey (VAY-see) in Charleston in 1822. After the Revolution, ship captain Joseph Vesey came to Charleston with his slave Denmark, whom he had purchased in the West Indies. In 1799, Denmark won $1,500 in the East Bay lottery. With $600 he bought his freedom. With the rest, he set to work as a carpenter. Together with a large number of blacks, he formed an African Methodist Episcopal church in 1815. As a class leader in the church, Vesey began to read the book of Exodus. He believed that God had called him to be the Moses of his people who would set them free from slavery. He began to recruit blacks to join the movement. He went from Georgetown to Beaufort. It was said he had 9,000 volunteers. Blacksmiths made pikes and daggers. Others stole pistols and powder. A barber made wigs and whiskers for disguises. Gullah Jack, who practiced voodoo, collected crab claws and parched corn for them to carry in their mouths to protect them. chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:27 PM Page 173 Vesey set the time for the revolt on the night of July 14. The moon would be in the last quarter, and many whites would be out of town. But on May 25, Peter Prioleau (PRAY-low), a slave of Colonel John Prioleau, told his master that a revolt was being planned. The colonel informed the mayor. The city council investigated, and on June 16, Governor Thomas Bennett called out the militia. In the end, 117 blacks were arrested. Seventy-nine of them were brought to trial before a special court. Sixty-nine were convicted. Thirty-five were hanged, and thirty-seven sold into slavery outside the state. Denmark Vesey and five of the leaders were hanged on July 2. They were true to the words of Peter Poyas (PIE-yas). “Do not open your lips!” he said. “Die silent as you shall see me do.” In the fall the legislature added more laws to the slave code, which had been adopted in 1740 after the Stono Rebellion. They further restricted the lives of free blacks. No free black person who left the state of his or her own free will could return. A head tax of $50 was placed on all free blacks who were born in the state or who had been residents for five years. Free blacks on ships sailing into ports in the state could not go ashore. They were put in quarantine on their ships. Every free black over fifteen had to have a guardian. If any person aided a slave revolt, he or she could be punished by death. The state set aside $100,000 to build two arsenals---the Arsenal in Columbia and the Citadel in Charleston--- to protect the white population. In 1842 the legislature converted them into military academies. Whites stopped criticizing slavery in South Carolina. They began to defend the institution. As early as 1808 the Methodists permitted slaveholders to join their churches. Quakers who did not change their views began to move into free states, like Indiana. Two sisters from a prominent Charleston family, Sarah and Angelina Grimké (GRIM-key), joined the Quakers, moved north, and became prominent anti-slavery leaders. In 1823, Dr. Richard Furman, pastor of the Charleston Baptist Church, wrote a defense of slavery. “The holding of slaves,” he wrote, “is justifiable by the doctrine and example contained in Holy Writ; and is, therefore consistent with Christian uprightness.” VI. THE NULLIFICATION CONTROVERSY What was Calhoun’s theory of Nullification? By 1824, American textile manufacturers asked Congress to raise the tariff on cotton and woolen cloth from Europe. Cheaper cloth from overseas was ruining Sarah and Angelina Grimké grew up in Charleston. They joined the Quaker Meeting and became convinced that slavery was wrong. MCS Oliphant Collection Where did the Grimkés move? Why? SC on Defensive | 173 chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:28 PM Page 174 Fort Hill was the plantation home of John C. Calhoun from 1825 to 1850. Today it is part of the Clemson University campus. Which of Calhoun’s writings is named for the plantation? their businesses. South Carolina leaders did not want a higher tariff. They said that European mill owners would punish American cotton growers by paying a lower price for cotton. However, Congress passed the Tariff of 1824, which raised the duty from 25 to 33 1/3 percent. The next year the price of cotton in Europe fell from 32 cents a pound to 13 cents. In 1827 manufacturers in the North asked for an even higher tariff. There were protest meetings all over South Carolina. In Columbia on July 2, President Thomas Cooper of South Carolina College spoke against the tariff and warned that the future of the United States was at stake. “We shall before long,” he said, “be compelled to calculate the value of our union.” In Charleston a wealthy planter, Robert J. Turnbull, wrote The Crisis. He argued that the tariff was unconstitutional and that the state should resist it. He urged that the state refuse to obey the law. Despite the protests, Congress passed the Tariff of 1828, which raised the duty to 50 percent. Opponents called it the “Tariff of Abominations.” Vice President Calhoun was in a dilemma. He was running for reelection. Yet he wished to help the state without openly defying the Constitution. He secretly wrote The South Carolina Exposition and Protest for a committee of the legislature. Calhoun took the position that Jefferson had once argued. The states, he said, existed before the nation. It was the states that voted for the Constitution and created the federal government. If a state believed the federal government had passed a law that was unconstitutional, then the state could nullify that law. That is, a convention of the people could meet and declare the law null and void within the bounds of the state. VII. A NATIONAL DEBATE ON NULLIFICATION What was the debate between Webster and Hayne about? In January 1830, the issue of nullification came before the United States Senate. Daniel Webster of Massachusetts attacked it. Robert Y. Hayne of Charleston responded, using Calhoun’s arguments from the Exposition. At the 174 | Chapter 15 chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:28 PM Page 175 time, Calhoun himself was presiding over the Senate as vice president. In his reply to Hayne, Webster gave one of the classic defenses of the Constitution. The people, not the states, he said, had created the federal government. A state could neither nullify a law nor secede from the Union: “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.” It became clear that Andrew Jackson would not support South Carolina. In fact, nullification was only one of a number of issues on which Jackson and Calhoun did not agree. Their feud became public in April 1830 at the Jefferson Day Dinner. Glaring at Calhoun, Jackson roared: “Our Federal Union — It must be preserved!” Calhoun, who refused to back down, replied: “The Union — next to our Liberties most dear.” VIII. NULLIFIERS VS. UNIONISTS What was the major disagreement between the Nullifiers and the Unionists? In South Carolina state leaders began to choose sides. Two parties formed. The States Rights and Free Trade Party were the Nullifiers, and the States Rights and Union Party were the Unionists. The Nullifiers persuaded Calhoun to support nullification openly. In July 1831, he wrote the Fort Hill Letter while he was at his plantation, Fort Hill, near Pendleton. Today Fort Hill is part of the Clemson University campus. After three years the Nullifiers had enough votes to nullify the tariff. But in the election in 1832 there was violence in the state. Armed mobs roamed the streets of Charleston. In Greenville, Unionist Benjamin F. Perry killed Nullifier Turner Bynum in a duel. Unionist Joel Poinsett was a secret agent for Jackson. He gathered information in the state and sent it to the president. When the votes were counted, the Nullifiers had the two-thirds majority in the legislature they needed to call a convention. The convention met in Columbia in November and nullified the tariff. In Washington, Jackson replied by issuing the Nullification Proclamation. He said that nullification was treason. He said he would use the army to enforce the Constitution. Congress supported the president by passing the Force Bill. It authorized him to use military power. In the meantime Hayne left his seat in the Senate to become governor of South Carolina. Calhoun then gave up his office as vice president to go to the Senate. On the Senate floor he debated the issue of nullification with Webster. But behind the scenes he worked with Henry Clay to lower the tariff and avoid a civil war. The Tariff of 1833, which Jackson gladly signed, reduced the duty over a period of nine years. South Carolina then repealed the Ordinance of Nullification. The crisis was over. But the state was marked as extremist. Even other states in the South were suspicious of its actions. Many prominent South Carolinians settled their disputes with a duel. These dueling pistols were used by Benjamin Perry and Turner Bynum during the nulification controversy. They are in the State Museum. S.C. State Museum On which side was Perry? Bynum? SC on Defensive | 175 chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:28 PM Page 176 EYEWITNESS TO HISTORY: South Carolina Exposition and Protest, 1828 Vice President John C. Calhoun secretly wrote a long essay for a committee of the South Carolina legislature to use in recommending that the General Assembly oppose the Tariff of 1828. He outlined the doctrine of states rights and why it permitted the state to nullify the tariff: . . . [The Federal] Government is one of specific powers, and it can rightfully exercise only the powers expressly granted, and those that may be “necessary and proper” to carry them into effect; all others being reserved expressly to the States, or to the people. It results necessarily, that those who claim to exercise a power under the Constitution, are bound to shew [sic], that it is expressly granted, or that it is necessary and proper, as a means to some of the granted powers. . . The Constitution grants to Congress the power of imposing a duty on imports for revenue; which power is abused by being converted into an instrument for rearing up the industry of one section of the country on the ruins of another. The violation then consists in using a power, granted for one object, to advance another, and that by the sacrifice of the original object. . . That there exists a case which would justify the interposition of this State [that is, the nullification of the tariff], and thereby compel the General Government to abandon an unconstitutional power, or to make an appeal to the amending power to confer it by express grant, the committee does not in the least doubt. . . Questions for Reflection: ? 1. Why did Calhoun not want his name attached to the Exposition? 2. Why is Calhoun’s theory of the Constitution called a strict construction, or states rights, interpretation? 176 | Chapter 15 Clyde N. Wilson and W. Edwin Hemphill, editors, The Papers of John C. Calhoun (Columbia, S. C., 1977), 10: 445ff. chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:28 PM Page 177 Recalling wha t you read I. Jacksonian Democracy 1. 2. 3. 4. In which state was Andrew Jackson born? What were the Jackson years known for as far as politics were concerned? How did Jackson see the role of government? What was introduced into campaigns for the first time? II. Jackson and the Democratic Party 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. How did Jackson become famous? Where did he establish his law practice and his plantation? How was he seen by his followers? What was the “spoils system”? What was the “kitchen cabinet”? How did Jackson control Congress? III. The Rise of the Whig Party FOR THOUGHT 1. What was Jacksonian democracy? 2. Why did slavery grow in the antebellum period in South Carolina? 1. Why did Jackson veto the bill to renew the charter of the Second Bank of the United States? 2. Who were the organizers of the Whig Party? 3. To whom did the Whigs appeal? 4. Name two Whig presidents. IV. South Carolina on the Defensive 1. What was South Carolina excited about following the election of 1828? 2. What two things were troubling to South Carolina? V. The Denmark Vesey Insurrection 1. What did the 1820 census show regarding the black population of South Carolina? 2. What were white South Carolinians fearful of? 3. Why did Vesey take a leadership role in the planned slave revolt? 4. Who was Peter Prioleau? 5. What was the outcome of the planned revolt? 6. How did the legislature try to control the possibility of future rebellions? 7. How did attitudes among whites change regarding slavery? continued on page 178 SC on Defensive | 177 chapter fifteen 2/26/06 8:28 PM Page 178 Recalling wha t you read VI. The Nullification Controversy 1. 2. 3. Why did South Carolina leaders not want Congress to increase the tariff on cotton and woolen cloth imported from Europe? What were the positions of Thomas Cooper and Robert Turnbull on the tariff? What was the important point Calhoun made in his secretly written The South Carolina Exposition and Protest? VII. A National Debate on Nullification 1. What was Webster’s argument against nullification? 2. What were the positions of Jackson and Calhoun on this issue? VIII. Nullifiers vs. Unionists 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 178 | Chapter 15 Who wrote the Fort Hill Letter and what did it support? When a vote was taken, which side had the majority? What was President Jackson’s reaction? How did Congress support him? What did Henry Clay and John Calhoun do to avoid a crisis and possible civil war?