McCarthy and the “Great Fear” - College of Urban & Public Affairs

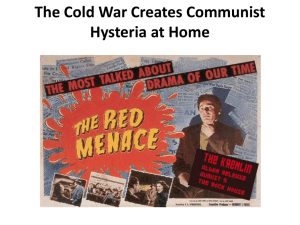

advertisement