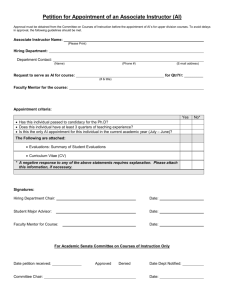

Federal Appointment Authorities - US Merit Systems Protection Board

advertisement