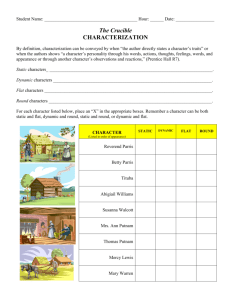

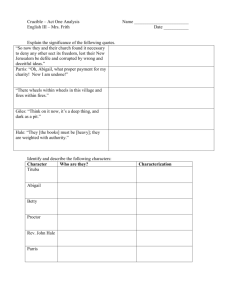

Focus and Motivate

advertisement