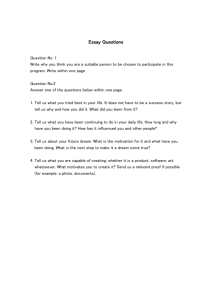

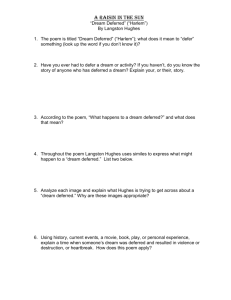

Poetry analysis: 'Dream Deferred' by Langston Hughes

advertisement

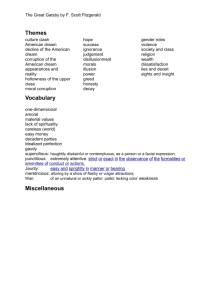

ARTS 23 The Epoch Times SEPTEMBER 12 – 18, 2012 Poetry analysis: ‘Dream Deferred’ by Langston Hughes Arthur Christopher Schaper Langston Hughes, one of the leaders of the early 1900s Harlem Renaissance, pushed the “black experience” beyond segregation and discrimination – from the back of the bus to front of the anthologies. His poems are read and enjoyed in classrooms throughout the country to this day. So pervasive has been the influence of his work, the line “a raisin in the sun” became the title of the acclaimed play by Lorraine Hansberry. “What happens to a dream deferred?” “Defer” at its core signals difference and delay, and dreams inevitably contain the germ of tardiness, or otherwise they would not be dreams, but present and apparent realities. “What happens” suggests that dreams just sit around and wait. Dreams do not exist in and of themselves, but are the product and profession of another, in the febrile mind of a fun man Dream Deferred What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore– And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over– like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode? –Langston Hughes (1902-1967) or the feverish demand of a weak personality. Dream deferred, the alliteration of noun and verb, announces the start and finish of this poem, the central goal of all that is taking place in this poem. Yet what does happen to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? A raisin in the sun, rays in the sun – the sun’s rays make the grape more sweet, more tough. Raisins last a long time and do not go bad. In the Bible, raisins are a sensuous source of strength: “Stay me with flagons [lit. raisin cakes], comfort me with apples: for I am sick of love.” (Song of Solomon 2:5) Raisins speak of sus- tenance, restoration, the culmination of great joy; just as time must pass for the grape to dry into a more delicious fruit. Or fester like a sore– And then run? A sore that festers – what a ghastly sight! This grim image imparts to the reader the lingering pain of a dream that waits to be realised, that waits to take place, that waits and waits, and then it runs. Yet in so sickening a sight, the notion of a “running sore” indirectly implies life and opportunity. A sore that runs is a mess that heals and in the same vein, a dream deferred will not remain ignored, but will break forth in the life of a man. Does it stink like rotten meat? Rotten meat, stinking like the sore, is waiting to be thrown away. Yet meat that rots, meat the stinks, is meat in which new life also lives. For what makes this stench so strong is the new creation of airborne life landing on a piece of flesh. Does the poet see this life? Does he see the seething meat as anything more than an eyesore? Or crust and sugar over– like a syrupy sweet? Now the poet rhymes meat with sweet. So much time is spent on the sound “ee” – is the dream, then, something to eat? Or does the dream still eat at the dreamer? “Crust,” a covering, protects the dream. “Sugar over” the crust is and does, a symbol both active and passive, that the “dream deferred” is neither lost nor forlorn. The dream gets bigger, gets smaller, but will not be static and stay still. Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. A dream that sags will not be still. The dream will not stay, like the smell, good or bad, that flies invisible from the sore, the meat or the raisins so sweet. Is this heavy load a burden that goes nowhere? The dream is a saggy dream that does more than “just” nothing – only this bag “justly” sags. Or does it explode? Dreams that explode, come to pass or pass through mind and heart, pressing past the staunch, stench sticking to the walls. The raisin does not explode, except in the mouth of a dry and weary traveller, renews his strength, gives him ease for the journey. The dream is now alive, refused to be put away. Not rotten, not running, not run down, but ready to be read. Dream Deferred draws out the dreams deferred in a reader. When the poet poses the question, the reader goes from wondering to pondering. The poem says a lot, like the rotting meat, teeming with life while seeming lifeless, like the dream that waits to be realised. The poem is so sweet, so juicy, unlike the dry raisin, yet just as tasty. The little poem backs a big bomb punch, “explodes” in the mind and beckons deferred dreams to fruition. Arthur Christopher Schaper is an author and teacher who lives in Torrance, Calif. He writes several blogs, including Schaper’s Corner (aschaper1. blogspot.com). Reading art: Laocoön and his sons Wim Van Aalst “The road to hell is paved with good intentions” is a common expression. Having good intentions is, of course, better than harbouring malicious ones, but who hasn’t caused a mess at one point in their life, despite their good intentions? Good intentions don’t always yield good results nor are they necessarily truly good. What is the story behind this sculpture? After years of war, the Greeks came up with the cunning plan to hide their troops in a huge wooden horse outside Troy and had Sinon, a Greek spy, convince the Trojans that the horse had magical powers. The suspicious Trojan priest Laocoön, however, tried his utmost to persuade his fellow citizens to burn the horse. Suddenly, he was struck with blindness. As he continued to try to persuade his brethren, one of the Greek gods (according to different versions of the story, this deity could be either Athena, Apollo or Poseidon) summoned a handful of deadly sea serpents to devour Laocoön and his two sons. The Trojans interpreted this event as a punishment Courtesy of BEJAN Design Laocoön and His Sons . from the gods for Laocoön’s throwing a spear at the wooden horse. So they promptly decided to haul the horse into the city. Thus, Heaven’s will decreed that the Trojans would be defeated. What seemed the right thing for Laocoön to do wasn’t what history wanted or needed to happen. Yet he meant so well. This large statue depicting Laocoön and his sons dates back to the first century BC and was excavated in Rome in 1506. Roman author Pliny the Elder attributes the statue to three sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros and Polydorus. It has been copied numerous times and has been in the possession of the Vatican Museums since 1816. Looking at the helpless trio in their death throes, wrestling with the tentacles of their doom, I find this scene a bit disturbing, yet without overstepping the boundaries of good taste. The whirling rhythm of limbs and serpents’ bodies has our eyes dancing about the scene and contrasts nicely with the vertical lines of the draperies, the symbol of their downfall. Laocoön is painfully exposed on a throne of his self-inflicted doom, while his two sons, the unwilling victims of their father’s actions, look to him for help – but it’s too late. A subject of debate about this sculpture has been the fact that while Greek literature compares Laocoön’s “horrendous cries” with the “bellowing of a wounded bull”, here he seems to be moaning rather than screaming with terror. The most probable explanation is what 18th-century writer, philosopher and art critic G.E. Lessing argued, namely, that portraying Laocoön with a wide-open mouth – truly bellowing – would have made the sculpture simply too painful to enjoy. Furthermore, such a depiction would have made it hard on the viewer to experience anything beyond the horror at the surface. As it is, the statue not only grips our attention, but it also has an emotional buffer to allow us to contemplate the theme behind the image: how we sometimes get defeated – or even harm others – because of uncalled for, or unwarranted, “good” intentions. Acting on uncalled-for good intentions is a pattern that humankind, deceived as much as ever, still hasn’t managed to outgrow, despite its dazzling scientific progress. Wim Van Aalst has a master’s degree in publicity and graphic design. He is a self-taught painter and teaches students in traditional oil painting techniques. Bowral & District Art Society, 1 Short St, Bowral 12 - 18 September 2012, 10am - 4pm Please join us for the official opening Saturday 15 September, 1pm with drinks and light refreshments served. www.en.falunart.org Contact: 0409 910 106 | Hosted by the Falun Dafa Association of NSW Inc