Exploring structure and agency in youth transition

advertisement

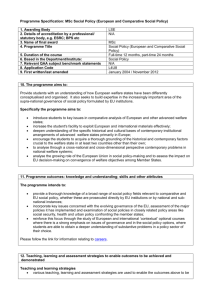

Lorenza Antonucci Post-graduate network session SPA Conference 2010 London School of Economics (LSE) Exploring structure and agency in youth transition Abstract: This essay aims to explore and introduce some methodological challenges faced in the comparative study of youth transitions. After summarising the scopes and aims of a research proposal concerning graduate youth transition in Sweden, England and Italy, it will focus on the methodological problems of considering the role of welfare structures (in particular the role of market, state and family) in influencing the individual experiences of transition. It will propose a research strategy based on “structured individualism” (France, 2007: 71) that combines the study of the macro-differences with the understanding of individual experiences. In order to discuss the methodological challenges, it will analyse the responses given by Swedish and English young people (the cohort 15-25) in the European Social Survey regarding the role of work and housing transition in becoming an adult. This essay will contend that a promising approach to the analysis of structure and agency is the use of vignettes and behavioural questionnaires that permit to explore the responses in different hypothetical situations. Introduction This essay aims to explore and introduce some methodological challenges faced in the comparative study of youth transitions. In particular, it will focus on the relationship between structure and agency, a crucial aspect that recurs in many other fields of social policy research. Firstly, the essay will briefly summarise the scopes and aims of my research proposal concerning graduate youth transition in Sweden, England and Italy, considering it in the larger framework of youth transition studies and youth transition literature. Secondly, it will focus on the methodological problems of comparative youth transition, proposing a research strategy of “structured individualism” (France, 2007: 71) that combines the study of the macro-differences with the understanding of individual experiences. Thirdly, it will discuss the notion of “dependency” as a crucial aspect summarising the dilemma between structure and agency. In particular it will analyse the responses given by young people (the cohort 15-25) of Sweden and England in the European Social Survey regarding the role of work and housing transition in becoming an adult. This example will permit to explore some challenges in interpreting the results and separating the role of the welfare policies from the experience of young people. The study of graduate youth transition In the last decades the experience of youth transition has been characterised by common trends across European countries: from a sociological perspective, studies on ‘young adulthood’ have underlined the extension of the passage from youth to adult life (Arnett, 2004). Most importantly, from a policy perspective, European and national policies have placed great emphasis on higher education as a crucial factor for guaranteeing ‘smoother transitions’ to adult life through easier access to work and social inclusion of young Europeans from lower-socio economic backgrounds (European Commission, 2007: 4). In the UK the increasing access to higher education of young people from disadvantaged families has been linked to the goal of improving social justice and social mobility (Hills, 2004: 121). Recent accounts of disparities in the experience of higher education between young people from lower socio-economic background and other students (Furlong and Cartmel, 2007; 2009) are shifting the focus from “access” to higher education to the social quality of this transition. Youth transition is defined here as an interstitial moment that includes diverse passages: from full-education to full-time employment, from the biological family to the family of destination and from the family home to independent housing (Jones and Wallace, 1992; Coles, 1995) 1 . The focus of my research regards an important socio-economic aspect of the transition: the use of social provisions that come from three main agencies (family, market and state). England, Sweden and Italy, considered here as ideal-types of transition to adulthood in Europe, present a different mix of these social interventions. The central question of my research is: how different sources of welfare, based mainly on work (England), state (Sweden) or family (Italy), impact on the experience of graduate transition of young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds? The research would focus on England, Sweden and Italy in order to isolate certain common contextual factors regarding the graduate experiences of youth transition in Europe, in particular the rise of unemployment and the higher participation of students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, and to consider welfare differences across Europe. The cross-national research design based on “most-different systems” comparison of welfare regimes in Europe allows us to find generalisible correlations (Della Porta, 2008) in the characteristics of European youth transitions. As underlined by Eurostudent (2008) there are three main sources of economic and social provisions during graduate studies across Europe: contributions from parents or relatives, state support and employment incomes. Sweden, England and Italy are emblematic ideal-types of different forms of welfare for graduate youth. In England, the market and labour have a crucial role in transition to adulthood, given the reduction of state benefits for the young form the 80s (Roberts, 1995), the introduction of workfare programmes (Mizen, 2004) and the increasing use of loans and market-based systems in education (Furlong – Cartmell, 2009). In Sweden, state provisions still play a central role in education and unemployment conditions, while in Italy and the Mediterranean model there is a central role for the family in providing housing and welfare provisions for transition to the adult life (Eurostudent, 2008; Guerrero, 2001). In order to disentangle the relationship between social provisions and experience of youth transition the research aims to explore the different experiences of transition of young people from disadvantaged families and the analysis of the socio-economic cleavages in transition. As shown in a pioneer study regarding the transition to employment (Furlong – Cartmel, 2008), graduates from lower socio-economic backgrounds have different experiences of transition to adulthood. A specific concern for this research would be to explore how forms of dependency (on family, state 1 This definition underlines the link between transitions and policies (employment, housing, family); moreover, it does not focus on a predominant structure, as common in the national-based literature, but includes different levels of transition (family, housing, employment) and therefore permits a truly European comparison and work) impact on the crucial passages of the transition (namely housing, family and employment). The central hypothesis of my proposal is that diverse sources of social provisions determine a diverse focal point in the individual experience of transition: e.g. given the importance of market and work in England the crucial point of the transition would be the access to the labour market. The contextual factor of rise in youth unemployment in these three countries gives the possibility of exploring the hypothesis concerning the “order of use in social provisions”: in a system based on work as a crucial factor of transition like England, during times of high unemployment rates, we would expect to see an increasing role of the family (as ‘residual’ welfare agency) in providing social services and postponing the transition to independent housing, in particular in young people from disadvantaged families. Limits and challenges in the study of comparative youth transition The analysis of the literature on youth transition presents several manifestations of the dilemma between structure and agency. Firstly, youth transition studies have been particularly embedded in national cultures (Bynner and Csisblom, 1998). The UK-based literature has defined youth transition as a specific phase in the life course between childhood and adulthood (Jones and Wallace, 1992), but also as a social group with a distinctive type of welfare need (Coles, 1995). These studies found specific ‘British’ paths in youth transition highlighting the polarisation of youth transitions between the ‘fractured’ transition of the so-called NEETs (young people not in Employment, Education and Training) and the less-studied transition from graduate education to work (Coles, 2000). As underlined by Fahmy (2006), this approach has focused on specific “problem groups” which reflect British society. Moreover, their focus on social divisions, although providing an understanding of how social differences contribute in determining diverse paths of transition, is hardly applicable to the new problems of youth experience, such as the graduate transition. A cross-national approach permits to challenge the existing categories and adapt youth studies to emerging problems and other structures. Secondly, youth studies have been challenged by the need of updating the understanding of the structure, determined by institutions and therefore national-based, to the changes in the agency, the experience of youth transition which became increasingly individualised given the fragmentation of old structures (family and state) in a risk-society (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim, 2001). Combining these aspects, the experience of youth transition is characterised by “structured individualism” (France, 2007: 71) in which individualistic pathways are determined by structural boundaries, in this case welfare state structures, that provide or limit choices and opportunities. A promising approach to the study of ‘structural individualism’ in the social policy of transitions is the adaptation of the welfare state regimes already present in the literature (Esping-Andersen 1990; 1996; Ferrera, 1996) to the graduate youth transition. Hammer (2001) applied the welfare state division to youth unemployment, while youth transition regimes have already been identified by Walther (2006) which focused on different general dimensions affecting the transition (e.g. employment, social security) and on specific dimensions of youth welfare (e.g. the different focus of transition policies in each welfare regime). The use of welfare regime division in youth transition has to adapt social policy notions to this area, as for the concept of “dependence”. As underlined by Coles (1995) social policies for youth are based on specific considerations of their “dependency” status (Guerrero, 2001). Contrary to “natural” forms of dependency on welfare in the case of the transition to adulthood, youth policies (education, housing, employment, social security benefits) create forms of dependency which are “functional” to the achievement of a form of independent status during adulthood. The double challenge of conducting a comparative study on youth transition concerns the problem of dealing, at the same time, with a longitudinal phase of the life-course (the transition from youth to adulthood) and to compare this phase across different countries. The necessity of combining ‘descending’ and ‘ascending’ research approaches in youth transition studies (Bynner and Csisblom, 1998) would justify the use of a mixed methodology in this field, in order to match key concepts to diverse cultural constructions of transition to adulthood. A first step, in order to explore the structure of transitions across Europe, would be a quantitative analysis across Europe, using the following data: 1. Eurostudent data set (2005-2008) contains 250 indicators from 25 countries, regarding the socio-economic background and living conditions during studies (in particular employment, housing, funding and income) in Italy, Sweden and England. The handbook allows for a quantitative descriptive assessment of different forms of welfare dependency in the three countries. 2. European Union Labour Force Survey: includes employment and unemployment data stratified by age (15-24) in EU countries. It allows for the analysis of the second part of the graduate transition, the relationship between employment and higher education (defined ‘tertiary education’) across countries. It gives the possibility to explore the similarities and differences between transition from education and employment in the three countries. 3. British Household Panel Survey (from 2010 incorporated in the UKHLS) it explores the life of household and it contains a specific form for young people (16-24) (youth questionnaire), asking questions on the aspiration about the future of young people. It gives the possibility of exploring family dependency and its relationship with ‘wealth of the household’ and transition to employment. It would also give a good understanding of how housing transition is changing and represents a ‘residual’ welfare source in British graduate transition as in the hypotheses. Unfortunately, there is no national equivalent in Sweden and Italy. A specific role in this analysis is played by the use of social attitudes: 4. European Social Survey, in particular round three (2006) that focuses on “life course and its timing” and includes specific questions on age and transition (such as the role of housing and employment transition in “becoming an adult”); it would improve the understanding of the specific focal point of transition in different countries. It involves Sweden and England, but not Italy. This database is particularly revealing for the analysis of youth transition: first, it permits to explore the attitudes of young people (e.g. disaggregating the data for the cohort 15-25) concerning the transition to the adult life or other relevant aspects of their life. Secondly, the comparative analysis of the European Social Survey for the same cohort (say, 15-25) permits to give a first understanding of the structural differences across countries perceived by the agency (young people). This understanding, however, is imperfect because we do not know if these ideas depend on the particular welfare structure present in the country or on different perceptions of the agency (young people). The quantitative analysis of data would give a macro perspective of the differences and similarities among countries regarding policy outcomes (in housing, employment and education) and youth attitudes. However, not all the quantitative data would be comparable and, for example, ESS and BHPS would present problems of representativeness, since the focus on graduate disadvantaged youth would reduce the original sample. These weaknesses can be partially complemented by the use of qualitative data from the second year of my study which would allow exploring more precisely the link between policy and the experience of transition, to obtain comparative data for the specific scope of this research and to explore “youth biographies”. This part is necessary to understand more about the perceptions of young people towards diverse forms of dependencies (from family, state and market) and therefore clarify the link between their individual experiences and the existing policy structures. Moreover, it is motivated by the necessity of assessing the functional equivalence of measures in different cultures (De Vaus, 2007), in this case of the notion of youth transition. Two research techniques seem particularly promising for the in-depth analysis of the agencies’ perceptions: — In-depth interviews to young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds in graduate transition in each country (Italy, Sweden and England) in order to explore their experience of transition. By using vignettes, it would be possible to explore the attitudes in hypothetical policy contexts where they would have diverse sources of social provisions. This would give the chance to evaluate and weigh how much perceptions of dependency depend on common experiences of fragmented transition across Europe or on available policy options in diverse European welfare systems. — In order to improve the external validity of the qualitative findings a potential research strategy would be to conduct a survey of young graduates at the end of their university experience. Rather than direct questioning, it would be interesting to employ behaviouralbased surveys that allow for the exploration of hypothetical situations. This type of techniques was used also in another cohort study: ELSA (English Longitudinal Study on Ageing). “Respondents were asked to assume that the hypothetical people used in the second section have the same age and background that they have. Anchoring vignettes are designed to take into account the fact that people of different countries, sex, age bands and socio-economic groups may rate similar circumstances differently. The questions enable analysts to see how different respondents rate themselves compared with how they rate the hypothetical examples. This information can be used to make comparisons between different groups or across time. They will facilitate cross-group and cross-country analyses as very similar questionnaires were used in the Survey of Health and Retirement in Europe and in the Health and Retirement Study in the United States” (Banks et al., 2008: 296) Dependency and attitudes towards transition to adulthood across countries A particular criterion for welfare state distinction for youth transition is the concept of dependence. As underlined by Coles (1995) social policies for youth are based on the specific considerations of their “dependency” status. Differently than concerning “natural” forms of dependency of the welfare in the case of transition to adulthood youth policies (education, housing, employment, social security benefits) create forms of dependency which are “functional” to the achievement of a form of independent status. Interestingly, the notion of dependency seems to be extremely influenced by the focus on the study of youth transition: in the study of Guerrero (2001), regarding the south of Europe, the issue of dependency is linked to the decision of postponing the house transition and it is essentially a dependency from the family. As underlined by Dean (2004) for the general study of welfare dependency, notions of dependency seem to be referred mainly to the family and state dependency, while the dependency from the market and the employers is less problematic or normalised. These findings have particular implications for youth transition studies: firstly, the moment of independence is crucial for the transition to adulthood. Secondly, different welfare state structures may lead to different processes of independency. Finally, the “myth” of independency characterising the individualised world of the risk-society might have an impact on this specific cohort and create a “stress for dependency” during the transition to adulthood. From a methodological perspective, the notion of dependency poses great challenges to the comparative analysis of youth transition and to the understanding of structure versus agency. In order to explore better this relationship, I will present some findings from the analysis of the European Social Survey (ESS) for England and Sweden, considering only the cohort 15-25 (which enters in the normal definition of youth). There are two questions in round 3 of the ESS which seem particularly appropriate for the analysis of welfare structure, the experience of transition and the notion of dependency. The questions that are considered are the following: “To be considered as adult, how important to have full-time job?” and “To be considered an adult how important is it for a man to have left the parental home?”. The answers were given with a scale from 1 to 9: 1 Not at all important 2 Not important 3 Neither important nor unimportant 4 Important 5 Very important 7 Refusal 8 Don't know 9 No answer These questions capture some peculiarities of the different structures between the two countries: the role of the family which has an impact on housing transition (Guerrero, 2001) and the possibility of finding the job which has an impact on the economic independence. As stressed before, England and Sweden present different “timing” in the house transition and a different role of the market in determining the independence and therefore the transition to the adult life. Image 1. “To be considered as adult, how important to have full-time job?”, Sweden (15-25) Image 2. “To be considered as adult, how important to have full-time job?” England (15-25) The answers given by young Swedish and young English people concerning the importance of a full-time job to be considered adult are remarkably different. In order to avoid “gee-weez” explanations (Jowell, 1998: 174) it is important to keep in mind the partiality of these findings, which are not taken from a cohort study and therefore might not be representative of the young people in the two countries. Interpreting the findings in the sample, we notice that, in general, young people in England in the sample give more importance to the fact of having a full-time job to be considered adult, compared to the Swedish young people. A relatively low percentage of Swedish young people consider having a full-time job very important to be considered an adult, while more than 50% of them consider it not important or not at all important. In England the distribution is less clear: more than 25% of young people consider it not important, but about 50% consider having a full-time job important or very important. The specific interpretation of these findings is affected by a general problem of cross-national analysis: do these findings depend on a cultural difference or on a difference in policies available to young people? We know from previous studies (Eurostudent, 2008; Mizen, 2004) that the transition to adulthood of British young people is more dependent on the job market than for Swedish young people, this also for a lack of state welfare sources to young people during the transition. These findings could be improved by an analysis with vignettes that allow separating hypothetical policycontexts from the effective structure present in the country. Image 3. “To be considered an adult how important is it for a man to have left the parental home?”, Sweden (15-25). Image 4. “To be considered an adult how important is it for a man to have left the parental home?”, England (15-25). The second answer concerns the importance of leaving the parental home to be considered an adult. In this case the question might be gendered (the question refers to the importance for a man) and this might affect the findings. The findings in the sample show a different situation compared to the importance of having a full-time job: in this case Swedish young people tend to give more importance to the housing transition than English young people. The distribution is more equally spread than in the case of full-time job, indicating that this factor is less revealing than the jobmarket of a national-specificity, but the number of young people considering the housing transition important or very important is higher in Sweden, while in England almost 40% of young people consider the house transition not very important. Also in this case the interpretation has to take in account the limit of this analysis: Swedish people might give more importance to the house transition because this event is “more typical” of the experience of transition to adulthood in Sweden. The linkage with the policies (and therefore with the structure) is not so clear, since we cannot separate the structure boundaries (or opportunities) from the individual experiences with a direct question. Also in this case it would be particularly useful to explore the perceptions of young people with an analysis of hypothetical contexts, in order to disentangle the relationship between policies and individual biographies. This type of study would clarify the cultural specificities in the elaboration of the notion of “independency” in the transition to adult life. Conclusion Youth transition to adulthood is a socially-constructed phenomenon that requires both an understanding of the structure and the experience of young people. The comparative analysis of welfare structures permits to analyse the contemporary experience of youth transition as a phenomenon of structured individualism. This essay has emphasised the methodological challenges of conducting comparative studies in youth transition, in particular focusing on the use of quantitative and qualitative data and on the interpretation of cross-national social attitudes surveys. Analysing the answers about the role of work and housing transition in becoming an adult of Swedish and English young people, the essay has emphasised the great differences across-countries. These results could be linked to the welfare-dependency during transition and to the diverse role of family, state and market across countries. However, there are still many challenges in the interpretation of these results as differences due to welfare structures. The use of vignettes or behavioural experiments might help to disentangle the relationship between youth experiences and structural differences. Bibliography: Arnett J.J. (2004) Emerging adulthood: the winding road from the late teens through the twenties, New York: Oxford University Press. Beck, U. and E. Beck-Gernsheim (2002) Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and its Social and Political Consequences, London: Sage. Banks, J. – Breeze, E. – Lessof C. and J. Nazroo (2008) Living in the 21st Century: Older people in England – The 2006 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, London: Institute of Fiscal Studies. Bison, I. and G. Esping-Andersen (2000) “Unemployment, Welfare Regime, and Income Packaging” in Gallie, D. and S. Paugam (eds.) Welfare Regimes and the Experience of Unemployment in Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 69-86. Bynner, J.and L. Cbisbolm (1998) “Comparative Youth Transition Research: Methods, Meanings, and Research Relations”, European Sociological Review 14:131-150. Coles, B. (2000) Joined-up youth research, policy and practice a new agenda for change? Leicester : Youth Work Press in partnership with Barnardo's. Coles, B. (1995). Youth and social policy: youth citizenship and young careers, London : UCL Press. Corijn M. and E.Klijzing (eds) (2001) Transitions to adulthood in Europe, Boston : Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001. Dean, H. (2004) The Ethics of Welfare, Bristol: Policy Press. Della Porta, D. (2008) “Comparative analysis: case-oriented versus variable-oriented research” in Della Porta D. and M. Keating, Approaches and methodologies in the social sciences a pluralist perspective, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.198-222. De Vaus, D. (2008) Comparative and Cross-national Designs in P Alasuutari, L Bickman, J Brannan & J Brannen, The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods, Sage, pp. 249-264. Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Cambridge: Polity Press. European Commission (2007) Employment in Europe 2007, Brussels: Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. European Commission (2007) Youth in Action, Brussels: Directorate-General for Education and Culture. Eurostat (2009) Eurostat News Release Euroindicators, December 2009 in http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/3-01122009-AP/EN/3-01122009-AP-EN.PDF [January 2010] Eurostudent (2008), Final Report in www.eurostudent.eu [June 2010] European Social Survey (Round 3) in http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ Fahmy, E. (2006) “Youth, Poverty and Social Exclusion”, in Gordon, D, Levitas, R and Pantazis, C (Eds.), Poverty and Social Exclusion in Britain: The Millennium Survey, Policy Press, pp. 347-373. Ferrera, M. (1996) “The “Southern” Model of Welfare in Social Europe”, Journal of European Social Policy 6 (1): 17–37. France, A. (2007) Understanding Youth in Late Modernity, London: Open University Press, 2007. Furlong, A. and Cartmel C. (2009) Higher Education and Social Justice, London: Open University Press. Furlong, A. and F. Cartmel (1997) Young people and social change: Individualization and risk in late modernity, Buckingham: Open University Press. Furlong, A. (ed) (2009) Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood: New perspectives and Agendas, Routledge, London. Guerrero, J. T. (2001). Youth in transition housing, employment, social policies and families in France and Spain, Hampshire: Ashgate. Hammer Y. (ed) (2001). Youth unemployment and social exclusion in Europe a comparative study, Bristol: Policy Press. Hills J. (2004), Inequality and the State, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Jones, G. and C. Wallace (1992). Youth, Family and Citizenship, Bristol: Open University Press. Jowell, J. (1998) “How Comparative is Comparative Research”, American Behavioural Scientist (42) 2, 168-177 Mizen, P. (2004) The changing state of youth, Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Roberts, K. (1995). Youth and Employment in Modern Britain, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Walther, A. (2006) ‘Regimes of youth transitions: Choice, flexibility and security in young people's experiences across different European contexts’, Young, May 1, 2006; 14(2): 119 – 139.