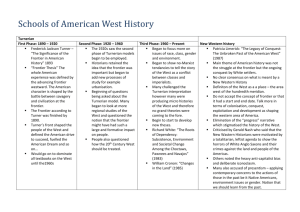

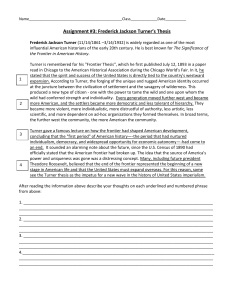

“Whatever be the truth regarding European history, American history

advertisement