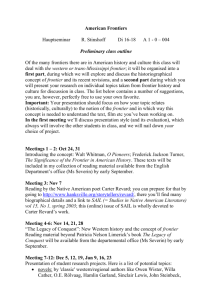

The Turner Thesis: A Historian's Controversy

advertisement

The Turner Thesis: A Historian's Controversy Author(s): J. A. Burkhart Reviewed work(s): Source: The Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Sep., 1947), pp. 70-83 Published by: Wisconsin Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4631887 . Accessed: 13/04/2012 00:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Wisconsin Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Wisconsin Magazine of History. http://www.jstor.org The TurnerThesis: A Historian's Controversy By J. A. BURKHART heard HistoricalAssociation of the American 1893MEMBERS FrederickJacksonTurnerread a paper entitled "The Significance of the Frontierin AmericanHistory." The paper had perhapsmore profoundinfluencethan any other essay or volume ever writtenin Americanhistoriography.Yet more amazingthan the influenceof this paperwas Turner'sability,living in the period about which he was writing, to discernthe effect of his era on Americanhistory. As part of the drift, Turnerwas able to chart the courseof the passingcurrentsof Americanlife. According to the Turner thesis, the American frontier has presenteda series of recurringsocial revolutionsin differentand changing geographicalareas as the tide of empire moved forwardto win a continentfrom a raw and hostile wilderness.'With constantre-exposureto relentlesssurroundings,reestablishingand readjustingan old way of life, and creatinga processof "starting again from scratch"and workingto a more advancedsociety, there resultedthat indefinablesomething which has been called Americanization.Its fundamentalsign was expansion; its chief conditionwas constantreadjustment;its final result was AmeriIN canization.' PROFESSOR J. A. BURKHARTis a member of the history faculty of Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri. In this paper he brings together the historians' "pros and cons" of the Turner frontier thesis. He concludes the controversy over Turner with the solution that is advanced by Professor John Hicks in his "The 'Ecology' of Middle-Western Historians," in the Wisconsin Magazine of History, 24:348 (June, 1941). Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York, 1921), 2. A number of excellent analyses and evaluations of the Turner thesis have been made. Among the most significant are the following: Avery 0. Craven, "Frederick Jackson Turner," in The Marcus W. Jernegan Essays in American Historiography (Chicago, 1937), 252-70; Joseph Schafer, "Turner's Frontier Philosophy," Wisconsin Magazine of History, 16:451-69 (June, 1933); and Frederic L. Paxson, "A Generation of the (March, 1933). Frontier Hypothesis," Pacific Valley Historical Review, 2:34-51 2 70 THE TURNER THESIS 71 Because the place where the most rapid change from the complex to the primitive occurred was on the outer fringe of the westward advance, Turner called this area "the frontier." Of great importance was that it lay "at the hither edge of free land." Turner observed its influence on the frontiersman: The wildernessmastersthe colonist. It finds him a Europeanin dress, industries, tools, modes of travel and thought.... Little by little he transforms the wilderness. But the outcome is not the old Europe.... The fact is that here is a new productthat is American.... Thus the advance of the frontierhas meant a steadymovementaway from Europe, a steadygrowthof independenceon Americanlines. And to studythis advance,the men who grewup in theseconditions,and the political,economic and socialeffectsof it, is to studythe reallyAmericanpartof our history.3 However, the word frontier is a study in sematics itself. Turner used it to denote many stages of the process. His writings describe various stages and gradations of its development. Turner has written of an Indian, hunter, trapper, and explorer stage; a squatter phase; an Indian removal step; and finally the advance of the Anglo-American settlement, the small farmer and settler, followed by capital and large scale enterprise.4 The result of this frontier process was a social devolution and evolution caused by the reversion of an advanced society to a simple and primitive culture and back again to a complex way of life. The slow climb back to complexity was not unlike that which mankind had experienced in the long march of civilization. The frontier process, however, was in a condensed state and proceeded at a much more rapid rate. Just as significant as the social evolution were the effects which this experience had on men, society, and institutions. The social and the cultural luggage carried by the settler in his journey westward were not thrown overboard, but new institutions and attitudes flavored by the frontier were invariably produced. Thus every frontier created many changes in the character of men and institutions. Turner, after discussing the frontier process, stated that the frontier promoted the formation of a composite nationality. As 8 The Frontier in American History, 4-5. 4 Ibid., 11-22. 72 J. A. BURKHART [September the population moved westward, dependence upon Europe wa3 ended and independence was begun. The European was Americanized. Pride in one's country and confidence in its future were encouraged. Frontier problems became national problems when men on the frontier called upon the government to do things for them. Local questions often became matters of national concern because of political exigencies or population mobility. "The economic and social characteristicsof the frontier worked against sectionalism" and "the mobility of population [was] death to localism." 5 Perhaps the most dramatic and pertinent element in the frontier was its democratizing influence. Turner assumed that democracy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries meant an increase in individualism, an expansion of voting rights, and a greater participation of the common man in the affairs of the state. Many times the word was used very loosely. At times Turner discussed democracy in reference to a frontier society in which the individual had relative social and economic equality; at other times he used the word to describe the broadening of the franchise and the increased participation of the individual in self-government or representative government.6 Working hand in glove with the democratizing influence, was the frontier stimulation of equality. The simplicity of society and the economic opportunity promoted by the presence of unoccupied land and unexploited natural resources generated an equality centered around competitive individualism. Equality, individualism, and democracy were all essential ingredients in the melting pot of the frontier. Sometimes this equality meant little more than the equal right to become unequal, together with the right to protest, complain, exploit, and grumble. In any event, the leveling influence, the eroding effect, and the worshipping of achievement all contributed to making the " Horatio Alger hero" a national model. Turner with his characteristic insight noted these conditions: It was not only a society in which the love of equality was prominent: it was also a competitive society. To its socialist critics it seemed not 5Ibid., 30. Ibid., 3 0-3 1. 1947) THE TURNER 73 THESIS so much a democracyas a societywhose memberswere "expectantcapitalists."... It was based upon the idea of the fair chance for all men, not on the conceptionof leveling by arbitrarymethods and especially by law.7 Finally, according to Turner, the frontier tended to change the character, qualities, and attitudes of the men and of the societies which they created. Western society had distinctive flavors. It had a psychosis conditioned and patterned by the forces which gave it birth: The West, at the bottom,is a form of society,ratherthan an area. It is the term applied to the region whose social conditionsresult from the applicationof older institutionsand ideas to the transforminginfluences of free land. By this applicationa new environmentis suddenlyentered, freedomof opportunityis opened,the cake of customis broken,and new activities,new lines of growth, new institutionsand ideals, are brought into existence.8 In like manner the West tended to develop specific qualities and characteristics in the men themselves. Some of the more prominent traits were: That coarsenessand strengthcombinedwith acutenessand inquisitiveness; that practical,inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients;that masterfulgrasp of materialthings, lacking in the artisticbut powerful to effectgreatends;that restless,nervousenergy,that dominantindividualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancyand exuberancewhich comes with freedom-these are traits of the frontier, or traitscalled out elsewherebecauseof the existenceof the frontier.9 The Turner thesis, expanded, interpreted, and circulated by his many followers, was accepted almost without reservation or criticism for more than a generation. Part of this was due, of course, to the merit of Turner's writing, and part of it was due to the tremendous personality of Turner himself. Even today any critical discussion of Turner in many quarters finds the air filled with pride and prejudice. However, in 1926 John Almack launched an indictment of many of the ideas which had been given respectability through their association with the frontier thesis.10 While Almack's article was overcrowded with details, it did clear the air and open the door for re-evaluation of much 8 Turner, The United States, 1830-1850 Frontier in American History, 205. (New York, 1935), 20. 9 lbid., 37. 10 John C. Almack, " The Shibboleth of the Frontier," Historical Outlook, 16:197-202 (May, 1925). 74 J. A. BURKHART [September that had previouslybeen written. A great deal of the evidenceadvanced in this article discountingthe influence and importance of the frontierseems on second sight to be simply window dressing. For example, in the statisticalcomparisonbetween the accomplishmentsof frontier and non-frontierareas in regard to general culture, education, land values, physical well being, national leaders,and so on, one wondersif Almack was not discussing foregoneconclusions.11 Yet the article contained much honest and sound argument. Almack rendersa real service in pointing out that the frontier was not the spearheadbehindmany governmentalreforms. Such importantinnovationsas equal suffrage,free tax supportedschools, direct legislation,civil service reform, primarynominations,and the recall owed their acceptancemore to labor forces than to the frontier process.2 Continuing this line of attack, Almack observedthat imitationand not inventionwas the rule when many of the frontier states drew up their constitutions.13To be fair, however,he should have pointed out that the frontiersmandid not have time to devote to such seemingly unimportantmatters as government. Making a living was a full-time job on the frontier,and any techniquewhich would save time found wide acceptance. Almack's attempt to compare present-dayfrontier areas with urban sectionshardly raises itself to the dignity of an argument. Taking Paxson'sdefinitionthat the frontier area consists of between two and six personsper squaremile, Almack observesthat today we have many sectionswhich would qualify as the frontier under such a definition. Further,such sections are among the most retardedin the nation. Speakingof the southernmountain region he states: "They are museumsin which have been preserved the log cabins, wooden plows, the sickle, the shuck mattresses,homemadesoap, the language of 1650, the muzzle14 loading rifle, and 'resentmentagainstgovernmentrestrictions.'" While such illustrationsare colorful,Almack mistakesruralism 1 Ibid., 199. 21bid. 13 14 Ibid. Ibid. 1947] THE TURNER 75 THESIS for the frontierand neglects the most vital element, the significance of the frontieras a process. In summary,Almack, while leveling a sixteen-inchgun at the frontier,generally hits his target with the explosive power of a pea shooter. His main contributionswere: (1) opening up the field for further investigation;(2) calling attention to the telling truth that American history was not shaped by any one factor but many; (3) pointing out that the Americanfrontier was not unique. Othercountries,notablyRussia,have had frontiers. Following Almack'sroundof fire, there seemed to be an open season on the Turner thesis. During the thirtiesa good deal of criticismappearedin various books and periodicals. A constant source of attack was against the uncriticalassumptionthat the words"frontier" and "democracy"were synonymous.Even some of the orthodox Turner students turned their guns against such obvious fallacies. As Avery Craven pointed out, freedom and equality on the frontier were sometimes little more than fine soundingwords. Freedomwas often only a physical freedom;it rarely meant freedom to think and to act differentlyfrom the group. Freedomwas at times only the liberty to do the things which everyoneelse did."5 Similarly,equality often meant nothing more than dragging the higher down to the level of the lower, a leveling force which poundedmen into a commonpattern. Conformityand uniformity were demandedby the group for its own protection. Individualism on the frontier, according to Carl Becker, was "that of achievementnot of eccentricity;of conformitynot of revolt."116 In addition,the frontierencouragedwaste and the exploitation of natural resources,moral and political irresponsibility,and occasionallya great deal of social injustice. Craven concludes that many times democracyon the frontier meant little more than a simple fluid society and economicopportunity.However, he quicklypoints out that alwaysthe flavorwas democratic,even though the practicewas not.17 15 Craven, Democracy in American Life (Chicago, 1941), 'I Quoted by Craven, ibid., 47. 17 Ibid., 46. 50. 76 J. A. BURKHART [September In fairnessto Turner,however,it should be made crystalclear that many of the ideas implicit in a liberal twentieth century conceptof democracywere not appliedby Turnerto the frontier. One should not try to read 1946 into 1800 or even 1893. The philosophy of democracyheld by Turner's g,enerationwas in many respects quite close to the political and social situations promptedby the frontier. Shifting the question from whether the institutions on the Americanfrontierwere democraticto whetherthe frontiercreated Americandemocracy,provides a fertile field for critical investigation. A strong criticismof the thesis is made on the grounds that it credits no other force, other than the frontier, for the promotion of American democraticinstitutions."8Turner himself contributedto this impressionby such statements as the " forest philosophyis the philosophyof Americandemocracy."19 In anotherplace Turnerwrote: "Americandemocracywas born of no theorist'sdream,it was not carriedin the 'Susan Constant' to Virginia, nor in the 'Mayflower' to Plymouth. It came out of the American forest, and it gained new strength each time 20 it toucheda new frontier." Such an interpretation,if followed blindly,ignoresthe elimination of feudalismin England,the developmentof representative governmentin Parliament,and does not considerthe liberalizing and democratizingforce of the ProtestantRevolt.21 It does not accountfor the seignorialsystem in Canadawhich outlastedand was at times more restrictivethan the contemporaryfeudalism of France. The frontierthesis does not explain why the government and society of the Dutch colonies were less liberal and democraticthan those of their English neighbors.22In short, attributing the growth and development of American democracy to the frontieralone neglects to evaluateproperlythe importance " American Democracy and the Frontier," Yale Review, 18 Benjamin Wrlight, Jr., n.s., 20:349-65 (December, 1930). "IFrontier in American History, 207. 20 Ibid., 293. 21 Wright, "American Democracy ...," 351. 22 Ibid., 355. 19473 THE TURNER THESIS 77 of our institutionaldevelopmentas an outgrowthof the evolution of Western civilization.23 Part and parcel of the Turner thesis was the idea that the frontierservedas a safety valve for the restless,the discontented, and the unemployed. This concept was taken at its face value and was not questioned for years. However, in 1935, Carter Goodrich and Sol Davison, writing on "The Wage-Earnerin the Westward Movement,"disputed the presence of any substantial number of wage-earnersin the Westward movement.24 A similar conclusionwas reachedby ProfessorKane, who held that the industrialworker could not accumulatethe minimum capital necessaryto exercisethe privilege of taking up farmlands in the West. Holding the opposite view from that which is generally accepted,MurrayKane argued that if any migration among the industrialworkersdid occur,the movementtook place not duringperiodsof depressionand panic,but duringthe upward sweep of the economic curve.25ProfessorShannon adds weight to the revisionistapproachby observing that no one has ever disproven the fact that after 1865 there were always at least 1,000,000 personsunemployedin this country.26 Dr. Joseph Schaferansweredthe critics on the validity of the safety valve theory by contendingthat as long as the land was not fully settled labor could not be cheap and by pointing out that even the critics (Davison and Goodrich) admittedthat the frontier tended to hold up the level of industrialwages. Also by using the manuscriptcensus, Dr. Schafercites statisticaldata proving that about one-third of the Middle Western farmers around 1880 had earned their farms as laborersor craftsmen. ProbablyDr. Schafer'sstrongestpoint, however, was in calling attention to the psychologicaleffect of the safety valve which operated alike upon laborers,employers,and the general pubIbid., 365. Political Science Quarterly, 50:184 (June, 1935). 25 Murray Kane, "Some Considerations on the Safety Valve Doctrine," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 23:169-88 (September, 1936). 2" Fred A. Shannon, "The Homestead Act and the Labor Surplus," American Historical Review, 16:650 (July, 1936). 23 24 J. A. BURKHART 78 (September lic.27 Irrespectiveof whether the frontier was an actual safety valve, the people thought that it was. Myth is many times more importantthan fact, and perhapsthe AmericanWest after the Civil War was a case at point. In 1936 ProfessorShannonwrote an article in which he disputed the common assumption,implied from the Turner thesis, that the year 1890 markedthe end of the free land in the West. By June 30, 1890, accordingto Mr. Shannon'sfigures, 372,659 homesteadentrieshad been completed,granting48,225,736 acres of land to homesteaders-an area which was less than the size of the State of Nebraskaand equal to only 3?V2percentof the land west of the MississippiRiver. Furthermore,four times as many acreshave been given away since 1890 than were distributedbefore that date. As a matter of fact, since 1910 more land has been taken up than was given away in all of the previousfortyeight years of the operationof the HomesteadAct.28 Bolstering his argumentthat the West was not filled by 1890, Mr. Shannon cites Delaware,a state with three countiesat low tide and two at high tide, as having in 1890 three times as many farms as Idaho and Montanacombined,three times as many as Wyoming, seven times as manyas Arizona,and eight timesas many as Nevada.29 Even consideringthe extent of land under cultivation,the East led the West. Ohio alone in 1890 had twice as many acres in farmsas the entire West.30 In the same article ProfessorShannon turned the searchlight on another long acceptedtenet of the Turner thesis-the availability of free land on the frontier. In discussingthe operation of the HomesteadAct, Mr. Shannonpoints out that the law did not provide any method of aiding the needy to reach the land, nor did it offerthem creditor guidanceduringthe "starvingtime " of early occupancy.31 The high cost of transportation,the expensivepracticeof "shoppingaround" beforesettling on the final destination,the savings-consumingperiod before the farm was Joseph Schafer, Was the West a Safety-Valve?" Misis7ippi via 2~ 2Q-l (neremherloi7)28Shannon, "Homestead Act...," 29 Ibid. 638. 639. 1'Ibid., 645. 'Ibid., Valey Historica Re- 1947) THE TURNER 79 THESIS on a self-sustainingbasis all contributedto the inferencethat the land was not really free, since it was not available. Professor BenjaminWright also cast suspicionon the presenceof free land in the West by intimatingthat the unoccupiedland may not have been free land.32 Of courseit might well be arguedthat the land on the frontier was never completely free since a person had to pay, in money or effort, for the cost of transportation.Furthermore,there was always expense involved in opening the land for cultivation;the land had to be cleared,fenced, and broken. Perhapsone had to scalp or be scalped by the Indians to retain possessionof his holdings. Finally a long period of time might elapse before any appreciativereturnfrom the land was realized. In a technicalsense the above conclusionsmay be true. Relatively speakingthe land was free when comparedwith real estate values in Europeand contributedmateriallyto the reductionof the price of land everywhere. Louis M. Hacker took a ratherdifferentand somewhatdoubtful approval in his criticism of the thesis. Mr. Hacker's chief grievanceswere Turner'scontention that America'sfrontier experiencewas uniqueand Turner'sfailure to view all of American historyin termsof the growthof Americancapitalism,the rise of imperialism,and the developmentof class antagonisms.33 It may be that Turneroverestimatedthe uniquenessof America's frontierexperience,but it still appearsas though the frontier process and the final results of this experienceare unexampled. The American farmer even today has a differentoutlook than the Europeanpeasant, and the American millionaire certainly has a differentperspectivethan the Europeanaristocracy.Rugged individualismand laissez-faireare still powerful forces in this country. Hacker seems to neglect entirely the importanceof the processby which we reachedcomplexity.Even though the frontier which helped to mould our national characterand our point of view is no longer in existence,the viewpointand the psychology 32 3 Wright, " American Democracy . . . ," 356. Louis M. Hacker, " Sections-or Classes," Nation, 37:108-10 (July 26, 1933). 80 J. A. BURKHART [September still remain.34There is still much in Americatoday which retains the frontier flavor. Indeed, sectionalismtoday has a greater influence over most Americans than does the appeal of class solidarity. Few Americanswould care to have themselves considered as anything other than middle class. Psychologicallyat least, we are in general a classlesssociety. Turner'scontention that the frontier producedspecific traits and qualitiesin men has also been attacked. Pierson,in a stimulating article, asks the following questionsand implies negative answers: (1) Is Turner'slist of American traits complete, or should it be modified by addition or deletion? (2) Were the Americantraits due solely to the influenceof the frontier? (3) Did not the frontierproducenegativequalitiesnot mentionedby Turnerin his writings? (4) Are the traitswhich we call American really American,or are they merelyhuman traitsfound in all partsof the world? (5) Were all social and racialgroupsequally affectedby the frontier?3 This matter of traits and qualities which go to make up the Western mind is very controversial.Most of the writerson the West, however,would assumethat it is a matterof degree rather than fundamentaldifferencesthat make the Western individual unique. To economize,the chief criticismsof the Turnerthesis revolve around the following points: (1) the safety valve concept is fallacious;the West never served as a haven or refuge for distressedlabornordidthe West guaranteethe existenceof democracy; (2) Turnerwrote about the West, particularlythe MiddleWest, neglecting such forces as labor, slavery,urbanism,and the influence of Europe; (3) Turnerfailed to evaluatethe importanceof the class struggle in America and its effect upon American history; (4) Western institutionsand frontier democracywere not unique; they followed and duplicatedthe same patterns as those in Europe and in the settled parts of the East. Even inThese ideas are contained in Avery Craven's article, "Frederick Jackson Turner," 258. mG. W. Pierson, " The Frontier and Frontiersmen in Turner's Essays; A Scrutiny of the Foundations of the Middle Western Tradition," Pentsylvania Magazine of History, 64:478 (October, 1940). 34 1947} THE TURNER THESIS 81 dividual traits in the West were not unique, but simply human traits found throughoutthe world and formed by other forces than frontierconditions;(5) the frontierthesis is a sectionaland one-sidedinterpretationof Americanhistory. In defense of Turnerone must quickly point out that not all of his criticshave fully understoodthe fundamentalcharacteristics of the frontier. Many of them have ignored the frontierprocess entirely and have concentratedtheir attack on relatively minor details. Other critics have ignored the contradictorynature and the almost certainimpossibilityof generalizations.For every asset of the frontierone can point out a negativecounteraction.One can say that the frontierwas lawless and immoral,and yet a church was often the first building to be erectedin a community. The frontiermay be criticizedas being unletteredand unlearned,yet few areashad more faith in the value of education. There was much idealismand even more materialism.The West worshipped success and efficiency,yet waste, exploitation,and failures were numerous;the saloon and temperancesocietieslived side by side; liberalism,reaction,laissez-faire,government aid, buoyancy,and discontentare hard to reconcile,yet all of these had their expression on the frontier; democratsbecame the worst kind of aristocratswhen they acquiredwealth; the frontiersmanhated privilege, but he was not adverseto "skimming a little cream" when the occasionarose.36 That Turnerseemedto recognizethe contradictionsof the West and did not repudiatethem is evident in his writingson nationalism and sectionalism.Hence it would be an easy matter to take statementson eithersubjectout of contextand pose generalizations which could be easily challenged. Accordingto Craven,Turner recognized the contributionsmade to American democracyby Europeat the very momentwhen he was insistingthat democracy was not carried in the "Susan Constant" to Virginia. Turner also recognizedthe individualismwhich existed side by side with community cooperation;the hostility toward government inter36John L. Harr, The Ante-Bellum Southwest, 1815-1861 1941), 6. (University of Chicago, 82 J. A. BURKHART [September ference coincidingwith the drought-stricken farmer'sdemandfor governmentaid.37 Nonetheless, some of the aspects of Turner's writing stand correctedand other phases requirefurtherstudy and exploration. It is quite likely that the West was not in actualitya safety valve for the oppressedindustriallaborerafter the Civil War. Moreover, it appearsthat Turnergeneralizedtoo much for the whole West on the basis of his knowledge of the Old Northwest. He probably emphasizedtoo strongly the peculiaristiccharacterof the Americanexperience,and he may have overshadowedthe influenceof other forces with his constantinsistenceon the significance of the frontierin Americanlife and history. Undoubtedly this is true in respect to democracy.Turner did not credit sufficiently Europeaninfluencesin accountingfor the growth and developmentof Americandemocraticinstitutions. Finally, it appears that Turnerwas a bit too enthusiasticfor the frontieras a characterand personality"Mix-master." A point generally obscured,however, must be kept in mind. Turnermerely advanceda hypothesis,a set of new ideas which might suggest a new approachto the study of Americanhistory. Much of that which passes as the "Turnerthesis" was taken up by his followers and offeredto the unthinkingas absolutestatements of universal truths. Many of his statementswere taken from their proper settings and circulatedamong the uncriticalas gospel doctrine. Thus such ideas as the following found wide acceptanceunder the attractivetitle of the "Turnerthesis": (1) the Americanfrontierwas unique; (2) all factorson the frontier encouragedand commandednationalismand democracy;(3) every frontiersmanwas inventive, individualistic,idealistic,progressive, and enthusiastic.Turner recognizedthese discrepanciesand once remarkedthat some of his students "apprehendedonly certain aspects" of his work and had not seen "them in relation" to the rest of his writing.38 Finally, historicalwriting should be reconsideredby each genM Quoted in Craven's "Frederick Jackson Turner," 257-58. 55Quoted in ibid., 256. 1947} THE TURNER THESIS 83 eration. Each generationshould judge for itself on the basis of availableinformationthe correctevaluationof historicalhappenings and historical interpretation.Without doubt Turner as a historianwould have been one of the first to offer amendments to his writingsin view of contraryfindings. It should also be rememberedthat Turnerwas suggestinga new approach,not dictating results; that he was presentinga case, not handing down a decision. Turner was simply calling attention to a field which had been long neglected; he was not attemptingto restrict the field from furtherwriting and investigation.Turnerwas a trail blazer, and as such he possessedthe merits and shortcomings of all pioneers. Perhapsthe most intelligent solution to the controversyover Turner is that advancedby ProfessorJohn Hicks. Accordingto Mr. Hicks, the truth lies somewherein betweenthe position that the frontierexplains Americanhistory and the revisionist'sstand that the frontier was only one factor in the development of America. Certainlyduring the seventeenth,eighteenth,and part of the nineteenthcenturythe ideaswhich Turnerwrote and spoke about were in general true, " ..people did go West, there was a frontier,and it made a difference." 3 However, close on the heels of the frontiercame a rising period of industrialismwhich also made a difference.But the historianof the future,recognizing the rightfulsphereof the two forceswill not attemptto " industrializethe frontier,or frontierizethe industrialperiod."40 39John D. Hicks, " The 'Ecology' of Middle Western Historians," Wisconsin Magazine of History, 24:348 (June, 1941). 1?Ibid.