Program notes by Jo Marie T. Larkin

advertisement

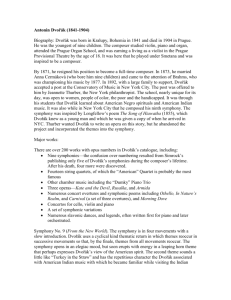

Program notes by Jo Marie T. Larkin Vitava (The Moldau) from Ma Vlast Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884) Bedrich Smetana was a Czech composer and conductor, and wrote the symphonic poem, “The Moldau” from Ma Vlast in 1874. Well-known for his nationalistic compositions, Smetana was best known for two nationalistic pieces: The Bartered Bride, an opera, and Ma Vlast, a cycle of six symphonic poems. Smetana was born in a small town in Bohemia, known today as the Czech Republic. He played violin and piano from an early age, and began composing when he was 8 years old. Smetana studied music composition in Prague and, in addition to being composer and a strong supporter of nationalistic Czech music, Smetana was a conductor, pianist, and teacher. Many of his works were programmatic with a nationalistic theme; in particular, his symphonic poems were influenced by Liszt. A symphonic poem, also known as a tone poem, is a programmatic orchestral work that expresses musical ideas such as emotions, scenes, or events through the music. Ma Vlast is an example of nationalistic music and program music, and represents Smetana’s deep love and beauty of his country, legends of the past, and great moments in Bohemian history. The best known of the six symphonic poems in Ma Vlast is the second, The Moldau (Vitava). Using programmatic compositional techniques to depict the Moldau River, the longest river in Czechoslovakia at nearly 300 miles, Smetana included the following description in a program he wrote to accompany The Moldau’s music score: “Two springs pour forth in the shade of the Bohemian forest, one warm and gushing, the other cold and peaceful. Their waves joyously rush down over their rocky beds, then unite and glisten in the rays of the morning sun. Coming through Bohemia’s valleys, they grow into a mighty river. Through the thick wood it flows as the joyous sounds of a hunt and the hunter’s horn are heard ever closer. It flows through the grass-grown pastures and lowlands where a wedding feast is being celebrated with song and dance. At night, wood and water nymphs revel in its sparkling waves. Reflected on its surface are fortresses and castles; witnesses of past days of knightly splendor and the vanished glory of bygone ages. The Moldau swirls through the St. John Rapids, finally flowing on in majestic peace toward Prague to be welcomed by historic Vysehard (a legendary royal castle), before it vanishes far beyond the poet’s gaze.” The opening flute ripple, like the sight of a river glimpsed in the far distance, is joined by the second flute’s ripples and the pluck of strings, drawing you into the swells of the landscape, growing ampler, mightier, until the scene the bursts free in a flood of strings and melancholy; it is the old land, the river that runs through it, “all the way from Smetana’s heart 125 years ago.” Concerto for Cello and Orchestra No. 1 in b minor Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904) Allegro Allegro ma non troppo Allegro moderato Antonin Dvořák began his Cello Concerto in New York in November of 1894, working simultaneously on sketches and the full score, and completed it in 1895. In response to the death of his sister-in-law, he composed a new coda for the finale at the end of that same year. With Dvořák conducting, Leo Stern gave the first performance in 1896, in London. The first North American performance soon followed, when Alwin Schroeder was the soloist and Emil Paur conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra. “ I have written a cello-concerto, but am sorry to this day I did so, and I never intend to write another,” said Antonin Dvořák to one of his composition students. “The cello is a beautiful instrument, but its place is in the orchestra and in chamber music. As a solo instrument, it isn’t much good.” These comments may surprise music lovers, who revere Dvořák’s Cello Concerto as one of the finest works in the orchestral repertoire and the standard by which all subsequent cello concertos have been measured. However, it was operetta composer and principal cellist with the Metropolitan Opera, Victor Herbert (who wrote Babes in Toyland), that changed Dvořák’s low opinion of the cello as a solo instrument. Inspired by Herbert’s “brilliant playing” as he performed his own cello concerto in 1894, Dvořák was inspired to finish the cello concerto he had started but left alone, “out of fear that the cello was too delicate and too low in pitch to compete successfully with an orchestra.” Although the cello concerto, like Dvořák’s New World Symphony, was written while he lived in America, it has no obvious American flavor. Instead of the New World’s extroverted and profoundly American energy, the cello concerto is a deeply personal Slavic work, full of beautiful and wellcrafted melodies. The first movement introduces two of Dvořák ’s most memorable themes. Low clarinet, joined by bassoons, with a somber accompaniment of violas, cells, and basses, lends itself to a remarkable series of oblique, multi-faceted harmonizations. The other, more lyrical, is one of the loveliest French horn solos in the literature. The tranquil mood in the Adagio section is quickly broken by an orchestral outburst that introduces a quotation from one of Dvořák ’s own songs, now sung by the cello in its high register with tearing intensity. The song, the first of a set composed in 1887-88, is “Kez duch muj san,” (“Leave me alone”), was a favorite of his earlier love, Josefina, now his sister-in-law. It was in her memory, after she died, that Dvořák added the elegiac coda. The song returns in the finale, and that coda stops the dance-like momentum. Dvorak wrote,” The finale closes gradually, with a diminuendo, like a sigh, with reminiscences of the first and second movements. The solo dies down, then swells again, and the last bars are taken up by the orchestra and concludes in a stormy mood.” Critics and audiences received the cello concerto with enthusiasm. The London Times praised “The wealth and beauty of thematic material, the development of the first movement, and the rich melodies in all three movements.” Johannes Brahms, in a letter to his publisher, wrote, “Cellists can be grateful to Dvořák for bestowing on them such a great and skillful work.” Symphony No. 1. Op. 17, in F Major Zdenĕk Fibich (1850-1900) Allegro moderato Scherzo—Allegro assai Adagio non troppo (alla romanza) Allegro com fuoco e vivace Zdenĕk Fibich’s career overlapped those of his countrymen Smetana and Dvořák, but his music remained poised between the twin poles of Czech nationalism and the New German School. His earliest surviving symphony is No. 1 in F Major, Op. 17, completed in Prague in 1883. An extraordinarily prolific and wide ranging composer, Fibich was one of the three supreme creators of Czech national music. Growing up in a highly cultivated bilingual household and dividing his school years between Vienna and Prague, Fibich had already composed fifty works by the age of fifteen when he left for Leipzig to perfect his musical training. The Symphony No. 1 is a relaxed, bucolic work that already reveals the hallmarks of his approach to sonata form; he cultivated a fine art of thematic transformation and applied it to all four movements. This, combined with a strong melodic vein and a penchant for unusual key schemes, gave his music a modern Czech flavor. Fibich’s three symphonies, like his principal operas, confirm him as a major world figure, merging the grace of Smetana, the easy folk-naturalism of Dvořák, and the refined charm of Tchaikovsky. He is considered one of the most gifted composers of music drama; Fibich succeeded on the opera stage with compositions acceptable to both the serious critics and the broader public. A very colorful description of how his First Symphony was received came from Novotny, who wrote; “Fibich was in his work exalted by many visions and phenomena of the romantic spirit, shady groves and oak woods with will-o’-wisps and wood-nymphs, ancient castles, hunting and feasting, the splendor of knightly jousting, of games and diversions, and other images of the romantic Middle Ages were all a spur to his creativity…” Right from the beginning of the symphony, the first bars radiate an atmosphere of extraordinary calm, a feeling experienced by an observer connecting with nature. The opening in the horns and violas depicts a ray of light which is rousing nature from the dark. Suddenly the flutter of a triplet figure, which will remain a key building and impelling element of the entire first movement, suggests nature’s whisper and rustle. Although Fibich begins his symphony in a meditative frame of mind, he also introduces a lyrical subsidiary theme before a part of the development section breaks the surface. At the very end of the movement, however, the opening returns, but in a totally different shape. The theme is heard in the full orchestra, bringing the movement to an end. In contrast to the dreaming, meditative, and triumphal first movement, the second movement is light-hearted and playful, cast in classic ABA form. The opening section (A), which is repeated, holds our attention with its lightness and virtuosity, representing Fibich’s childhood game-playing in the woods. The middle (B) section is different in that it carries echoes of folk music, of the Polka dance. The third movement is perhaps the most characteristic one. After the playful and frolicsome second movement, we enter a world of poetry, of ballad. The opening theme in oboe and horn seems to be telling of knights, fallen comrades, mysterious castles, and old ruins. The accompaniment in the harp, supported by string pizzicatos, evokes the sound of the lute, the very instrument linked with medieval and renaissance imagery. An even more somber mood enters before the music takes on a completely different character with its distinctly folk-like quality before we are led back to the earlier theme. The movement ends quietly, in the same calm manner with which it began. The fourth movement was probably written much earlier that the rest of the symphony. Two themes return several times in various forms, but before we hear the closing coda which rounds off the symphony in a virtuoso manner, a last reminiscence of the opening theme of the first movement makes its appearance as if interrupting the flow of the music and calming the atmosphere. The final section is then all the more thunderous, bring the work to its end. The First Symphony of Zdenĕk Fibich ends in a triumphal spirit.