character analysis explanation

advertisement

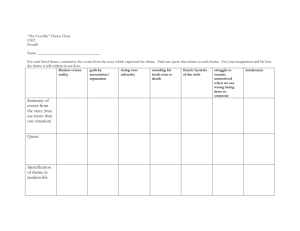

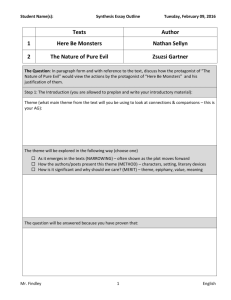

How to Write a Character Analysis A strong character analysis will: 1. Identify the type of character. 2. Describe the character. 3. Discuss the conflict in the story, particularly in regards to the character’s place in it. 1. Identify the type of character. A single character could be two or three types. Characters can be ▪ protagonists*, The main character around whom most of the work revolves. The character who changes the most significantly. ▪ antagonists, The person or force who opposes the protagonist in the central conflict. This is often the villain, but could be a force of nature, set of circumstances, an animal, etc. ▪ major, These are the main characters. They dominate the story. ▪ minor, These are the characters who help tell the major character’s tale by letting major characters interact and reveal their personalities, situations, stories. They are usually static (unchanging). ▪ dynamic (changing) ▪ static (unchanging) ▪ stereotypical (stock), This is the absent minded professor, the jolly fat person, the clueless blonde. ▪ foils, These are the people whose job is to contrast with the major character. This can happen in two ways. One: The foil can be the opposite of the major character, so the major’s virtues and strengths are that much “brighter” in reflection. Two: The foil can be someone like the major character, with light versions of the major’s virtues and strengths so that the major comes off as even stronger. ▪ round (3 dimensional), This means the character has more than one facet to their personality. They are not just a hardcore gamer, but they also play basketball on the weekends. ▪ flat (1 dimensional), This is the character who is only viewed through one side. This is the hardcore gamer. That’s all there is to the character. *The protagonist is often the hero and can follow literary patterns or types: ▪ the anti-hero (Holden Caufield), This is the guy your mother would not want you or your sister to date. They are often graceless, inept, and actually dishonest. ▪ the tragic hero (Oedipus, Macbeth), This is the guy whose bad end is a result of flaws within himself. ▪ the romantic hero (Don Juan, James Bond), This is the guy the girls all swoon over. He gets the girls, even when he doesn’t want to keep them. ▪ the modern hero (Chuck Bartowski), This is the average guy who is put in extraordinary circumstances and rises to the challenge. ▪ the Hemingway hero, This is the guy who has been in a war, drinks too much, gets his girlfriend pregnant, and she dies. Or guys like him. 2. Describe the character. Consider the character’s name and appearance. ▪ Is the author taking advantage of stereotypes? The hot-tempered redhead, the boring brunette, the playboy fraternity guy. ▪ Is the author going against stereotypes? The brilliant blonde, the socially adept professor, the rich but lazy immigrant. ▪ Is the author repeating a description of the character? If so, then it is important. For example, Kathy in East of Eden is described as rodent-like and snake-like, “sharp little teeth” and a “flickering tongue.” ▪ Is their name significant? Is it a word that means something, like Honor or Hero? Does it come from a particular place or time and make reference to that? Scarlett, Beowulf. ▪ Does the author connect the character to any important stuff? Is he or she surrounded by or regularly referred to linked with a specific object or objects? ▪ Appearance and visual attributes are usually far less important than other factors, unless their appearance is the point– such as in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Clothing also rarely matters, except to make him/her easier to visualize. Consider if he/she a static (unchanging) or dynamic (changing) character. If the character has changed during the course of the story: ▪ Was the change gradual or rapid? ▪ Was it subtle or obvious? ▪ Are the changes significant to the story or are they a minor counterpoint? ▪ Are the changes believable or fantastic? ▪ What was his/her motivation to change? ▪ What situations or characters encouraged the change? ▪ How does the character learn from or deal with the change? Consider how the author discloses the character: ▪ By what the character says or thinks, and HOW he/she says it. ▪ By what the character does. ▪ By what other characters say about him/her. ▪ By what the author says about him/her. ▪ The short form for this is STAR (says, thinks, acts, reacts). Look for these things within the creation of the character: psychological/personality traits ▪ Do these characteristics aid in the character being consistent (in character), believable, adequately motivated, and interesting? ▪ Do the characteristics of the character emphasize and focus on the character’s role in the story’s plot? motivation ▪ Is the character ethical? Is he/she trying to do the right thing, but going about it in the wrong way? ▪ Is the motivation because of emotion (love, hate) or a decision (revenge, promotion)? behavior /actions ▪ Does the character act in a certain way consistently? ▪ Or is the character erratic? ▪ Could one pluck the character from the story, put them in another story, and know how they would react? relationships ▪ With other characters in the story ▪ How others see/react to him/her weaknesses/faults ▪ Typical tragic weakness is pride. Oedipus is proud. ▪ Weakness could be anything. In “Little Red Riding Hood,” the girl talks to a stranger. That’s a weakness. strengths/virtues ▪ There are many different strengths and virtues. ▪ One strength/virtue is being good in trying times, like Cinderella. ▪ Another strength/virtue is caring for family, like Little Red Riding Hood. ▪ Another strength/virtue is being smart, like Oedipus. ▪ Most protagonists have more than one strength/virtue. moral constitution ▪ Often a character will agonize over right and wrong. ▪ If a character doesn’t agonize and chooses one or the other easily, that is also significant. protagonist/antagonist ▪ Does the story revolve around this character’s actions? ▪ If so, is the character the hero (protagonist) or villain (antagonist)? complex/simple personality ▪ Personalities are more likely to be simple in children’s stories, fairy tales, and short stories. ▪ Personalities are more likely to be complex in longer works. ▪ Even in short works, such as “The Story of an Hour,” the character’s personality can be complex. Then it depends on what the author was focusing on. history and background ▪ Sometimes a character analysis looks at the history of the individual character. Was that person mistreated? abused? well-loved? liked? ▪ Sometimes the history of the work matters more. Is the story set in World War II? In ancient Greece? That makes a difference because culture changes stories. If you don’t know the culture, though, you may not be able to comment on this. similarities and differences between the characters ▪ This could be the foil aspect again. ▪ It could be looking at how characters complement each other. ▪ It could be looking at why characters would be antagonistic. character’s function in story ▪ Is the character an integral character? (Cinderella) ▪ Is the character a minor character? (The wicked stepmother in “Cinderella”) ▪ Is the character someone who could have been left out or is gratuitous? (The second wicked stepsister in “Cinderella.”) 3. Discuss the conflict in the story, particularly in regards to the character’s place in it. Types of conflict include: External – ▪ man vs. man: This is the protagonist versus the antagonist. Snow White versus the Wicked Queen. ▪ man vs. machine: This is when the machine is the enemy. Many robot-centric novels have this issue. (This is sometimes considered a subset of man vs. man.) ▪ man vs. nature: Robinson Crusoe on the island. Hansel and Gretel lost in the forest. ▪ man vs. animal: Captain Ahab versus the white whale in Moby Dick. The wolf in “The Three Little Pigs.” –Usually the animal is a predator and the man has become prey for some reason. It could be humorous, though, the man is trying to catch the dog, who runs away and has the main character chasing him all over creation. (This is sometimes considered a subset of man vs. nature.) ▪ man vs. fate or destiny: Sleeping Beauty can’t help pricking her finger. A man who has been late several times (due to circumstances beyond his control) gets in a traffic jam and is an hour late to work and gets fired. The fact that it has happened several times and is not his fault is the crucial point. ▪ man vs. society: This is when a character battles societal norms. Winston Smith in 1984. Huck in The Adventures of Huckleberrry Finn. Internal – ▪ man vs. himself: This is when the character has an ethical dilemma, stealing to feed his family or watch them starve. Lie to the government and save the people in the basement or tell the truth and have them taken away. This is the cartoon equivalent of the devil and the angel on either shoulder. **This information was borrowed (and minimally adapted) from www.teachingcollegeenglish.com . How to Write an Analysis of Theme What is it? Analysis of theme involves working the concept, thought, opinion or belief that the author expresses. It is very common (and helpful) to consider theme when analyzing another aspect of literature rather than on its own. The theme of a work is the main message, insight, or observation the writer offers. The importance of theme in literature can be overestimated; the work of fiction is more than just the theme. However, the theme allows the author to control or give order to his perceptions about life. How do you find the theme? Sometimes the theme can be discovered by reading through the work and looking for topics that show up again and again. When you were reading the work, did you think, “Ah, didn’t he already talk about that?” If you did, then you have probably noted a theme. If you are having trouble picking out a theme, examine the relations among the parts of a story and the relations of the parts to the whole: Characters: What kind of people does the story deal with? Plot: What do the characters do? Are they in control of their lives, or are they controlled by fate? Motivation: Why do the characters behave as they do, and what motives dominate them? Style: How does the author present reality? Does he habitually use long or short sentences? What kind of paragraphs are there? Are they short and conversational or are they long and involved? Is the work divided up? If so, how and where? Tone: What is the author’s attitude towards his subject? Values: Does it seem like the author is making a value judgment? What are the values of the characters in the story? What values does the author seem to promote? Think about how the author conveys his ideas. Consider: o Direct statements. o Imagery and symbolism. o A character’s thoughts or statements. o A character who stands for something (e.g. an archetype*) o Overall impression/tone/moral of the work Can you identify major and minor themes? A short story probably only has one theme. A novel often has several. Discovering minor themes Are there recurring images, concepts, structures OR two contrasting ones? Motifs often support minor themes. How can allusions make a difference? An allusion is a figure of speech wherein a phrase which is culturally recognizable is used as a type of shorthand for something else. Often allusions are used to make a large point quickly. “He was a Houdini” means he can get out of tight situations. He might even be an actual escape artist. Are there any allusions? Are these historical, biblical, modern? You will not be able to recognize allusions if you do not know the cultural reference, so many readers looking at a work will miss the allusions. If you happen to be knowledgeable about the allusions in the work, this might be a good point for you to begin with. If there are multiple allusions about a particular topic, that is a good indication that the topic is a theme in the work. An example of the beginning of a theme analysis A major theme in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is growing up. Throughout the work Alice changes size twelve times. People change size when they grow up. The size change equating to growing up is also a metaphor; in English the description “being bigger” often means “being older.” For the purposes of the story, Alice grows both larger and smaller, but with each change, Carroll is symbolizing Alice’s maturation process. Each time she grows larger or smaller, she has to deal with a problem related to the change in her size. The very first size change comes when she has recklessly followed the White Rabbit down the hole and into Wonderland. She found a key which unlocked a door, but she could not go through it because she was the wrong size. This fantastical situation happens often in real life. As children are growing up, they often feel that they are not the right size to do whatever they want to do. One day they might feel that they should be bigger so that they might go wherever they wished and the next day they might feel that they should be smaller so they do not have to do chores. Thus Alice’s desire to be a different size in the very first chapter of the book indicates that growing up is a major theme in the work. Of course, the analysis is incomplete, but it shows how a theme analysis might start. **This information was borrowed from www.teachingcollegeenglish.com . Close-Reading of a Quote Consider the following: 1. Speaker - Who is saying the quote? 2. Context - What is happening in the story when the quote occurs. 3. Literary Devices - Are any specific devices being used? If so, for what purpose? 4. Significance - What does the quote mean? What does it reveal about the speaker? Does it hold any symbolic significance? Does it reflect anything about a conflict, motif, theme, etc in the story? One would assume that if you have chosen a specific quote to examine (or your teacher has chosen one for you) then it must be significant in some way. Book Review This information was borrowed (and modified) from www.writing-world.com/freelance/asenjo.shtml . Remember: • Include title and author. • Hook the reader with your opening sentence. Set the tone of the review. • Review the book you read -- not the book you wish the author had written. • If this is the best book you have ever read, say so -- and why. If it's merely another nice book, say so. Don’t hyperbolize or you lose credibility. Points to Ponder: Note: You don't have to answer every question -- they're suggestions! • • • • • • What was the story about? Who were the main characters? Were the characters credible? What did the main characters do in the story? Did the main characters run into any problems? Adventures? Who was your favorite character? Why? Your personal experiences • Could you relate to any of the characters in the story? • Have you ever done or felt some of the things, the characters did? Your opinion • Did you like the book? • What was your favorite part of the book? • Do you have a least favorite part of the book? • If you could change something, what would it be? (If you wish you could change the ending, don't reveal it!) Your recommendation • Would you recommend this book to another person? • What type of person would like this book? Response to a Critical Analysis Essay Read and annotate a published critical analysis essay by a credible scholar. These can be found at Bloom’s Literary Database (under the subheading Facts on File) or EBSCOhost, both of which are on Mr. Shearer’s Media Center page. Mr. Shearer can provide you with a sheet of passwords to access these databases from home. You do not need the passwords when accessing them on school computers. After you read and annotate the essay, consider whether you agree or disagree withe the author’s ideas. In your response, present his/her ideas and your thoughts about them. If it is a long essay, you may choose to focus on one or two ideas. It is better to pull apart and explore a limited amount of ideas than cover more information in a very broad or vague manner. Make sure you staple to annotated critical analysis essay into your journal.