Alcohol in Finland in the early 2000s

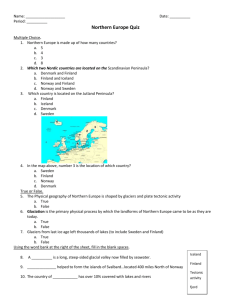

advertisement