The Mindlessness of Ostensibly Thoughtful Action: The Role of

advertisement

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

1978, Vol. 36, No. 6, 635-642

The Mindlessness of Ostensibly Thoughtful Action:

The Role of "Placebic" Information in

Interpersonal Interaction

Ellen Langer

Harvard University

Arthur Blank and Benzion Chanowitz

The Graduate Center

City University of New York

Three field experiments were conducted to test the hypothesis that complex

social behavior that appears to be enacted mindfully instead may be performed

without conscious attention to relevant semantics. Subjects in compliance paradigms received communications that either were or were not semantically sensible, were or were not structurally consistent with their previous experience, and

did or did not request an effortful response. It was hypothesized that unless the

communication occasioned an effortful response or was structurally (rather than

semantically) novel, responding that suggests ignorance of relevant information

would occur. The predictions were confirmed for both oral and written communications. Social psychological theories that rely on humans actively processing

incoming information are questioned in light of these results.

Consider the image of man or woman as a

creature who, for the most part, attends to

the world about him or her and behaves on

the basis of reasonable inference drawn from

such attention. The view is flattering, perhaps,

but is it an accurate accounting of covert

human behavior?

Social psychology is replete with theories

that take for granted the "fact" that people

think. Consistency theories (cf. Abelson et al.,

1968), social comparison theory (Festinger,

1954; Schachter, 1959), and attribution

theory (Heicler, 1958; Jones et al., 1972;

Kelley, 1967), for example, as well as generally accepted explanations for phenomena

like bystander (non)intervention (Darley &

Latane, 1968), all start out with the underlying assumption that people attend to their

The authors are grateful to Robert Abelson for his

comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript and

to Cynthia Weinman for conducting Experiment 1.

Requests for reprints should be sent to Ellen

Langer, Department of Psychology and Social Relations, 1318 William James Hall, Harvard University,

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138.

world and derive behavioral strategies based

on current incoming information. The question raised here is not whether these formulations are correct, nor is it whether people are

capable of thoughtful action. Instead, we

question how often people outside of the laboratory are actually mindful of the variables

that are relevant for the subject and for the

experimenter in the laboratory, and by implication, then, how adequate our theories of

social psychology really are.

This article questions whether, in fact, behavior is actually accomplished much of the

time without paying attention to the substantive details of the "informative" environment.

This idea is obviously not new. Discussions of

mind/body dualism by philosophers and the

consequences that different versions of this

relation have on its status as an isomorphic,

deterministic, or necessary relationship between the two are part of psychology's heritage. However, the extent of the implications

of this idea has not been fully appreciated nor

researched. How much behavior can go on

without full awareness? Clearly, simple motor

acts may be overlearned and performed auto-

Copyright 1978 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 0022-3514/78/3606-0635$00.7S

635

636

E. LANGER, A. BLANK, AND B. CHANOWITZ

matically, but what about complex social interactions?

The class of behavior of greatest interest

here is not that which is commonly understood to be automatic, such as walking or

typewriting, but rather that which is commonly assumed to be mindful but may be, in

fact, rather automatic. We shall refer to it

here as mindless behavior—mindless in the

sense that attention is not paid precisely to

those substantive elements that are relevant

for the successful resolution of the situation.

It has all the external earmarks of mindful

action, but new information actually is not

being processed. Instead, prior scripts, written

when similar information really was once new,

are stcreotypically reenacted. Berne (1964)

discussed the idea of scripts in a popularized

way, and Abelson (1976) rigorously elaborated the concept in generating a computer

simulation of belief systems. To Abelson,

a script is a "highly stylized sequence of

typical events in a well-understood situation,

. . . a coherent sequence of events expected

by the individual, involving him either as a

participant or as an observer." (p. 33) (See

Author's note, p. 642.)

The notion of a script was used -to describe

a study by Langer and Abelson (1972),

where it was argued that asking a favor had

certain script dimensions and that the success

of getting compliance depended on the specific

syntax of the request rather than on the

specific content of the statement, fn that

study, the words making up the request were

held constant, while the order of the words

spoken was varied. The opening words determined which script was followed, and compliance varied accordingly. Similar to the notion

of script is Goffman's (1974) concept of

frames, Harre and Secord's (1973) idea of

episode, Thorngate's (1976) idea of caricature, Miller, Galanter, and Pribram's (1960)

notion of plans, and Neisser's (1967) concept

of preattentive processing. Each of these formulations speaks 1,0 the individual's ability

to abide by the particulars of the situation

without mindful reference to those particulars.

However, while Abelson has come closest

to delineating the structure of scripts, no one

has yet experimentally determined the minimum requirements necessary to invoke a par-

ticular script, nor has scripted behavior really

been demonstrated to be mindless. While the

former issue is not addressed in the present

article, the latter is the article's main concern,

and we may shed some light on the requirements for script learning and enactment once

the mindlcssness of ostensibly thoughtful

actions has been demonstrated. This suggests

that the essence of a script may not lie in

recurring semantics but rather in more general

paralinguistic features of the message. When

we speak of people organizing incoming information, it is as important to take into

account what they systematically ignore as it

is to take into account what they systematically process. And when we speak of people

ignoring information, it is important to distinguish between information that is ignored

because it is irrelevant and information that

is ignored because it is already known. It is

known because it has been seen many times

in the past, and aspects of its structure that

regularly appear indicate that this time is just

like the last. Thus, what is meant by mindlessness here is this specific ignorance of

relevant substance.

This article reports three field experiments

undertaken to test the mindlessness of ostensibly thoughtful action in the domains of

spoken and written communication. It was

hypothesized that when habit is inadequate,

thoughtful behavior will result and that this

will be the case when cither of two conditions

is met: (a) when the message transmitted is

structurally (rather than scmantically) novel

or (b) when the interaction requires an effortful response.

Experiment 1

Method

The first experiment was conducted in the context

of a compliance paradigm, where people about to

use a copying machine were asked to let another person use it first. The study utilized a 3 X 2 factorial

design in which the variables of interest were the

type of information presented (request; request plus

"placcbic" information; request plus real information) and the amount of effort compliance entailed

(small or large).

Subjects. The subjects were 120 adults (68 males

and 52 females) who used the copying machine at

the Graduate Center of the City University of New

MINDLESSNESS OF OSTENSIBLY THOUGHTFUL ACTION

York. Each person who approached the machine on

the days of the experiment was used as a subject

unless there was a line at the machine when the

experimenter arrived or a person came to use the

machine immediately after a subject had been approached. (There was a minimum wait of S minutes

between subjects). Half of the experimental sessions

were conducted by a female who was blind to the

experimental hypotheses, and the remaining sessions

were run by a male experimenter who knew the

hypotheses.

Procedure. Subjects were randomly assigned into

one of the groups described below. The experimenter

was seated at a table in the library that permitted a

view of the copier. When a subject approached the

copier and placed the material to be copied on the

machine, the subject was approached by the experimenter just before he or she deposited the money

necessary to begin copying. The subject was then

asked to let the experimenter use the machine first

to copy either 5 or 20 pages. (The number of pages

the experimenter had, in combination with the number of pages the subject had, determined whether the

request was small or large. If the subject had more

pages to copy than the experimenter, the favor was

considered small, and if the subject had fewer pages

to copy, the favor was taken to be large). The experimenter's request to use the machine was made

in one of the following ways:

1. Request only. "Excuse me, I have S (20) pages.

May I use the xerox machine?"

2. Placebic information. "Excuse me, I have 5 (20)

pages. May I use the xerox machine, because I have

to make copies?"

3. Real information. "Excuse me, I have S (20)

pages. May I use the xerox machine, because I'm in a

rush?"

Once the request was made and either complied or

not complied with, the experimenter returned to the

table and counted the number of copies the subject

made. The dependent measure was whether subjects

complied with the experimenter's request.

If subjects were processing the information

communicated by the experimenter, then the

rate of compliance should be equivalent for

Groups 1 and 2, since the amount of information conveyed is the same for both of

these groups, but it might be different for

Group 3, since this group received additional

information. If, however, subjects are responding to the situation on the basis of a

prior script that reads something like "Favor

X + Reason Y —> Comply," then the rate of

compliance should be the same for Groups 2

and 3 (placebic and real information) and

greater than for Group 1 (request only). It

was predicted that the latter result would obtain. Thus, while the information given to

Group 2 was redundant in an information

637

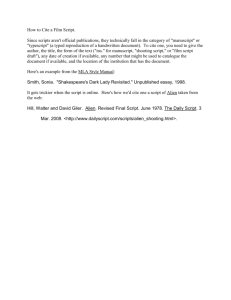

Table 1

Proportion of Subjects Who Agreed to Let the

Experimenter Use the Copying Machine

Reason

No

Favor

info.

Small

n

.60

IS

Big

.24

25

n

Placebic

info.

Sufficient

info.

.93

15

.24

25

.94

16

.42

24

theory sense (Shannon & Weaver, 1949), it

was predicted to be necessary, and thus not

redundant, in a script sense.

As stated earlier, it was assumed that people would not behave in this pseudothinking

way when responding was potentially effortful. Then, there is sufficient motivation for

attention to shift from simple physical characteristics of the message to -the semantic

factors, resulting in processing of current information. Thus, it was predicted that as the

favor became more demanding, the placebicinformation group would behave more like

the request-only group and differently (yielding a lower rate of compliance) from the

real-information group.

Results and Discussion

The proportion of subjects who complied in

each group was computed, and a 3 X 2 X 2

(Request X Effort X Experimenter) analysis

of variance was performed using 0 and 1 as

scores (complied vs. did not comply). This

analysis yielded three main effects: communication, F(2, 108) = 3.02, p< .05; effort,

F(l, 108) = 43.40, p<.001; and experimenter, F(l, 108) = 6.67, p < .01. The proportions of subjects who complied with the

different requests are presented in Table 1.

Not surprisingly, the female experimenter had

a higher rate of compliance than the male

experimenter, but since there were no interactions between this variable and the others',

the data are combined in the table for ease of

reading. A contrast analysis using planned,

orthogonal comparisons was performed. The

contrast analyses that were performed set the

small effort/placebic-information group and

the small effort/sufficient-information group

638

E. LANGER, A. BLANK, AND B. CHANOWITZ

as equal to each other but distinct from the

small effort/no-information group; the large

effort/sufficient-information group was contrasted with the large efforl/placebic-information group and the large effort/no-information group. These contrasts reflect the hypothesis that when there was small effort

involved, the placebic-information group

would be similar to the sufficient-information

group but that when effort was large, the

placebic-information group would be similar

to the no-information condition. It was found

that for the small-effort contrast, the means

of the placebic- and sufficient-information

conditions were virtually identical and significantly different from the no-information condition, F(l, 114) =6.35, p < .05. For the

contrast comparing the more effortful favor,

the no-information and placebic-information

groups were identical and tended to be different from the sufficient-information group,

^(1, 114) = 2.83, .10 <p> .05.

Also, and not surprisingly, for requests of

the same type, small requests result in greater

compliance than larger requests.

The results support the hypothesis that an

interaction that appears to be mindful, between two people who are strangers to each

other and thus have no history that would

enable precise prediction of each other's behavior, and in which there are no formal roles

to fall back on to replace that history, can,

nevertheless, proceed rather automatically.

1 f a reason was presented to the subject, he or

she was more likely to comply than if no

reason was presented, even if the reason conveyed no information. Once compliance with

the request required a modicum of effort on

the subject's part, thoughtful responding

seemed to take the place of mindlessness, and

the reason now seemed to matter. Under these

circumstances, subjects were more likely to

comply with the request based on the adequacy of the reason presented.

Experiment 2

The next two experiments attempted to extend the results of Experiment 1 to the domain of written communications, since it is

our contention that pseudothinking behavior

is more the rule than the exception for prac-

tically all verbal behavior as well as nonverbal

behavior. The more one participates in any

activity, the more likely it is that scriptlike

qualities will emerge. Through repeated exposure to a situation and its variations, the

individual learns to ignore and remain ignorant of the peculiar semantics of the situation.

Rather, one pays attention to the scripted cue

points that invite participation by {he individual in regular ways.

In Experiments 2 and 3, we sought to engage subjects in an activity that would have

for them scripted qualities. Specifically, the

activity we chose involved receiving and responding to letters and memoranda that were

sent through either the U.S. Mail or interoffice mail, depending on the study. As in

Experiment 1, it was assumed that ostensibly

thoughtful action would proceed mindlessly as

long as the structure of the activity involved

remained consistent with its scripted character.

Following this assumption, we expected that

individuals who received mail that asked for

a response would return what was requested

if the communication was structurally phrased

so as to follow the commonly expected script

for mail. The return of the response would

serve as evidence of the fact that the person

had read the material and engaged in the

activity of correspondence through the mail.

If the communications to the subject were

semantically senseless and yet fulfilled the

script requirements for written communication, we could safely assume that the return

of the mail signified that we had engaged the

subject in mindless behavior—that he or she

had not "thought about" the material but had

returned it merely because it satisfied the

structural requisites for a habitual behavior.

To make the case more strongly, we sent to

the subjects communications that were equally'

senseless semantically but which varied in

their adherence to the structural requirements

of communications. If the responses varied

directly with the adherence to structural consistency expected in communications, we could

infer that the behavior that led to the subjects' returns was of a scripted character—

entirely habitual, despite the fact that, on the

face of it, if we observed the behavior we

MINDLESSNESS OF OSTENSIBLY THOUGHTFUL ACTION

would assume it was thoughtfully processed

in character.

In Experiment 2, subjects were mailed a

meaningless, five-item questionnaire. The

cover letter either demanded or requested the

return of the questionnaire and was either

signed (e.g., "Thank you for your help,

George L. Lewis") or unsigned. It was assumed that signed requests and unsigned

demands were more congruent with the structure of most written communications than unsigned requests and signed demands and

therefore would be more conducive to sustaining mindless behavior. The cover letter had

no letterhead and could not possibly, with

thought, be construed as representing a legitimate authority. Therefore,

"thoughtful"

processing of the cover letter would not uncover any rational reasons for returning the

questionnaire.

In order to test whether habitual responding was taking place, rather than merely

polite compliance, two groups of subjects

were selected who were assumed to vary in

their experience with written communications.

It was predicted that the more experienced

subjects (who were also the more educated

subjects) would be more likely to return the

questionnaire when the structure of the request/demand was consistent with their past

than the less experienced subjects, for whom

congruency was not expected to matter.

Method

Subjects. Forty subjects were selected randomly

from the Manhattan telephone directory and constituted the random-status group. Another 40 subjects

were chosen randomly from the "Physicians" section

of the Manhattan Yellow Pages and constituted the

high-status group.

Procedure. Each subject received a questionnaire

in the U.S. Mail consisting of the five following questions:

1. The subway or bus is the more enjoyable mode

of public transportation ?

2. Movies or plays are the more enjoyable form of

public entertainment ?

,3. Libraries or parks are the more enjoyable form

of free public entertainment?

4. Forests or playgrounds are the more enjoyable

public places to spend time ?

5. Cash or credit cards is the more efficient form of

public exchange of goods?

All subjects received the questionnaire at their residence. Along with the questionnaire, the subjects

639

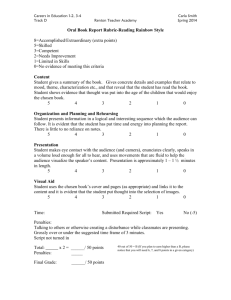

Table 2

Proportion of Subjects Who Returned the

Questionnaire

Status

Condition

High

Congruent

n

Iricongrueiif

n

.55

20

.20

20

.32

19

.37

19

received a stamped envelope addressed to a post

office box, as well as a cover sheet that varied in one

of the following four ways:

1. Congruent conditions, (a) Request/personal—"I

would appreciate it if you would fill out the attached

questionnaire and return it in the enclosed envelope

to me by September 10. Thank you for your help,

George L. Lewis," (h) Demand/impersonal—"The

attached questionnaire is to be filled out and returned by September 10."

2. Incongnient conditions, (a) Request/impersonal

—"I would appreciate it if you would fill out the

attached questionnaire and return it in the enclosed

envelope to me by September 10." (b) Demand/personal—"The attached questionnaire is to be filled out

and returned in the enclosed envelope by September

10. Thank you for your help, George L. Lewis."

Thus, the study was a 2 (random vs. high status)

X 2 (request vs. demand) X 2 (personal vs. impersonal) factorial design. Again, it was predicted that

high-status subjects who received congruent communications would be more likely to comply than

the other groups.

Results and Discussion

Table 2 presents the proportion of subjects

who returned the questionnaire, by congruence and status.1 An analysis of variance was

performed using 0 and 1 scores. Although

there were no main effects, a contrast that set

the high-status congruent group as different

from the remaining groups, which in turn were

equal to each other, was significant at p <

.OS, F(l, 74) = 5.91. The congruent and incongruent cells of Table 2 are broken down

for examination in Table 3. The analyses of

variance of these data were not significant.

However, there was a trend for a three-way

interaction, F(l, 70) - 3.48, p < .08, which

indicates again that the congruency effect

1

Two of the original letters were returned with

the notice that the addressee no longer lived at the

address. Hence, there were 78 subjects in the study.

E. LANGER, A. BLANK, AND B, CHANOWITZ

640

Table 3

Proportion of Subjects Who Returned the

Questionnaire

CoudiUon

High status

Random status

Vet1msonal personal

Per1msonal personal

Demand

n

.33

9

.40

10

.44

9

.20

10

Request

n

.70

10

.30

10

.20

10

.30

10

tends to be modified by status. It appears that

our notion of what is congruent was correct

only for people like ourselves, who have had

an abundance of certain kinds of written communications and not others. That is, instead of

there being a general script for written communications, there are probably several scripts

peculiar to individuals in their relation to social institutions. In fact, on second thought,

it seems that communiques sent from employer to employee, or from manager to office

worker (the latter two probably comprised

much of the random-status group), would

more than likely be either of the demand/

personal or request/impersonal sort, since

these forms allow the sender to maintain his

or her status while still observing a modicum

of civility.

Experiment 3 was undertaken to test

again, more rigorously, the mindlessness of

ostensibly thoughtful actions in regard to

written communications. However, for this

study, the script was first determined empirically and then tested.

Experiment 3

Method

Eighty-three memoranda were collected from the

wastepaper baskets of 20 secretaries of various departments at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Sixty-eight percent of these

had the request/impersonal form described earlier.

While varying in content, each of these communications requested rather than demanded that the secretary do something (e.g., "Please make 20 copies of

this"), and none were signed at the bottom of the

request. Thus, for this group of people, the communication most congruent with their experience

would be request/impersonal. Even though in these

instances the receiver in all likelihood knew who the

sender was, this kind of communication is still con-

sidered impersonal, since it stands in contrast to

those communications where the sender also is known

but where the memo is signed just the same. The

distinction between signed and unsigned memos is

being drawn, in spile of the fact that in both cases

the sender is known, because small structural differences of this kind arc predicted to either cue in a

script or not, depending upon one's past experience.

The remaining 32% of the memos were virtually

equally distributed among the other categories. With

this in mind, 40 secretaries at the Graduate Center

were sent, through interoffice mail, a senseless memorandum that was either congruent with their experience or incongruent. In order to allow for comparisons with Experiment 2, the same four forms of

written communication that were used previously

were randomly sent to these subjects. However, now

there were one congruent form (request/impersonal)

and three incongruent forms (request/personal, demand/personal, domand/impcrsonal) :

Request. "1 would appreciate it if you would return this paper immediately to Room 238 through

interoffice mail."

Demand. "This paper is to be returned immediately

to Room 238 through interoffice mail."

Half of each of these messages were signed ("Sincerely, John Lewis"), and half were unsigned and

merely had a number (R374-021-A) at the bottom of

the message.

Nothing more was written on the memo. Subjects

were simply asked to return a piece of paper that

asked them only to return that paper to Room 238.

The designated room did not exist in the building.

The mailroom attendants put the returned letters

aside for us.

Thus, the study utilized a 2 (request vs. demand)

X 2 (personal vs. impersonal) factorial design, with

10 subjects in each cell.

Results and Discussion

Table 4 presents the proportion of subjects

who returned the letters as a function of the

various conditions. To test the hypothesis that

mindless behavior will result when script requirements arc met, the proportions of subjects who returned the memo in the congruent

condition (.90) and the incongruent conditions (.60) were compared. Using 0 and 1

scores, the analysis showed them to be significantly different from each other, i(38) —

1.78, p < .05. It should be noted that what

we are calling congruent was determined by

sampling a fraction of the secretaries' past

experience with written

communications.

Sixty-eight percent of the memos fell into the

request/impersonal condition. Quite possibly,

if we had mapped out first what was congruent for each secretary and then sent the appropriately structured-for-congruence memo

MINDLESSNESS OF OSTENSIBLY THOUGHTFUL ACTION

to her or him, the compliance might have

reached 100%.

Experiments 2 and 3 provide support for

the mindlessness hypothesis in regard to written communications. It would seem that

thoughtful processing of the information communicated to these subjects would have resulted in a nonresponse from them. Nevertheless, when the script was congruent with subjects' experience, 55% of the physicians and

90c/(, of the secretaries complied with 'the

meaningless communication.

Conchisions

These studies taken together support the

contention that when the structure of a

communication, be it oral or written, semantically sound or senseless, is congruent with

one's past experience, it may occasion behavior mindless of relevant details. Clearly,

some information from the situation must be

processed in order for a script to be cued.

However, what is being suggested here is that

only a minimal amount of structural information may be attended to and that this information may not be the most useful part of

the information available. While the authors

do in fact believe that people very often

negotiate their interpersonal environments

mindlessly, studies like these may simply

demonstrate that subjects are not thinking

about what one thinks -they are thinking about

(i.e., what is relevant), rather than demonstrating that their minds are relatively blank.

If we knew all of the things subjects could be

thinking about, we could use the present experimental paradigm to at least test this

alternative. However, since there are an infinite number of thoughts subjects may be

thinking, this strong hypothesis will have to

remain at the level of conjecture until other

experimental methods are devised. The difficulty of inventing such a methodology

should not preclude efforts in that direction,

since if mindlessness is the rule rather than

the exception, man}' of the findings in social

psychology would have to be reformulated

(see Langer, 1978, for a more detailed discussion of this point).

While these studies ma}' be open to alternative interpretations, they suggest that per-

641

Table 4

Proportion of Subjects Who Returned the Memo

Memo type

Condition

Personal

Impersonal

Demand

.60

.50

Request

.70

.90

Note, n = 10/cell.

haps there has been misdirected emphasis on

people as rational information processors. Instead of viewing people as either rational or

irrational, it would seem wise to at least consider the possibility that their behavior may

be arational and yet in some way systematic.

These studies then raise questions about the

inferential processes traditionally assumed by

cognitive social psychology. This has been

alluded to by Bern (1972) and more recently

by Dweck and Gilliard (197S). It may not be

that a person weighs information and then

proceeds but that he or she more often just

proceeds on the basis of structural cues that

occasion further regular participation in the

interaction. To the extent that this script

domination is typical of daily interaction, corrections must be made in our accounts of how

individuals behave.

When does this mindless activity take

place? If the interpretation offered for these

studies is correct, then it would suggest that

the occurrence may not be infrequent nor

restricted to overlearned motoric behavior like

typewriting. Instead, if complex verbal interactions can be overlearned, mindlessness may

indeed be the most common mode of social

interaction. While such mindlessness may at

times be troublesome, this degree of selective

attention, of tuning the external world out,

may be an achievement (cf. Langer, 1978)

and perhaps should be studied as such. At

least it would seem that both the advantages

and disadvantages should be investigated, as

the boundaries of the phenomenon are delimited. At present, however, we may be in

the uncomfortable position of ovcrgencralizing

our laboratory findings for reasons not yet

mentioned by laboratory-research critics.

Once an individual is brought into the laboratory he or she is likely to be self-conscious.

642

E. LANGER, A. BLANK, AND B. CHANOWITZ

This self-consciousness may be thought provoking and habit inhibiting. Thus, we may

be left with the situation where we are studying the responses of thinking subjects and

then generalizing to successfully nonthinking

people.

Author's nole. Since the Langer and Abclson (1972)

paper was published, there have been diverging uses

of the terra script which did not become apparent

until after this manuscript was prepared. The clarification of the present distinction lies in the degree

of active information processing implied by the

word script. Abelson's use of the term script seems

to allow a range of cognitive activity. In our

formulation, the use of script signifies only relative

cognitive inactivity. To avoid confusion, the word

script as it appears in this article should be read as

"mindlessncss."

References

Abelson, R. P. Script processing in attitude formation

and decision-making. In J. S. Carroll & J, W.

Payne (Eds,), Cognition and social behavior. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1976.

Abclson, R. P , Aronson, E., McGuirc, W. L., Newcomb, T. M., Rosenberg, M. J., & Taunenbaum,

P. H. (Eds.). Theories of cognitive consistency:

A sowcebook. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1968.

Bern, 1). J. Self-perception theory. In L. Berkowilz

(Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology

(Vol. 6). New York: Academic Press, 1972.

Berne, E. Games people play. New York: Grove

Press, 1964.

Daricy, J. M., & Latanc, B. Bystander intervention

in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 1968, 8, 377383.

Dweck, C., & Gilliard, D. Expectancy statements as

determinants of reactions to failure: Sex differences

in persistence and expectancy change. Journal oj

Personality and Social Psychology, 1975, 32, 10771084.

Feslingcr, L, A theory of social communication processes. Human Relations, 1954, 7, 117-140.

Goffman, E. Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. New York: Harper & Row,

1974.

Heider, F. The psychology oj interpersonal relations.

New York: Wiley, 1958.

Harrc, H., & Secord, P. F. The explanation of social

behavior. Totowa, N.J.: Litllefield, Adams, 1973.

Jones, E. E., Kanouse, D. E., Kellcy, H. II, Nisbctt,

R. E., Valins, S., & Weiner, B. Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior. Morristown, N.J.:

General Learning Press, 1972.

Kclley, H. H. Attribution theory in social psychology.

In D. Levine (Ed,), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (Vol. IS). Lincoln: University of Nebraska

Press, 1967.

Langer, E. J. Rethinking the role of thought in social

interaction. In j. Harvey, W. Ickcs, & R. Kidd

(Eds,), New directions in attribution theory (Vol.

2 ) . Hillsdalc, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1978.

Langer, E , & Abelson, R. P. The semantics of asking

a favor; How to succeed in getting help without

really dying. Journal oj Personality and Social

Psychology, 1972, 24, 26-32.

Miller, G. A., Galanler, E., & Pribram, K. H. Plans

and the structure oj behavior. New York: Holt,

Rinehart & Winston, 1960.

Ncisscr, U. Cognitive psychology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1967.

Schachter, S. The. psychology of affiliation. Stanford,

Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1959.

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. The mathematical

theory of communication. Urbana: University of

Illinois Press, 1949.

Thorngate, W. Must we always think before we act?

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1976,

2, 31-35.

Received January 25, 1978 •