Example 1 - University of Cincinnati

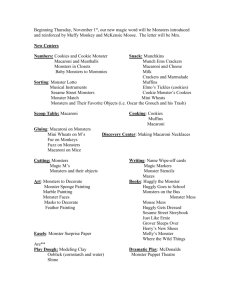

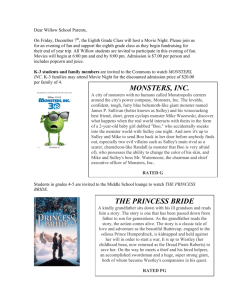

advertisement