The 20-minute team – a critical case study from the emergency room

advertisement

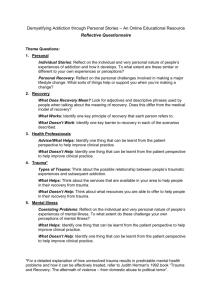

Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice ISSN 1356-1294 The 20-minute team – a critical case study from the emergency room Johan M. Berlin MA PhD1 and Eric D. Carlström MA PhD2 1 Senior Lecturer, Director of Studies, Assistant Director of Research, Göteborg University, School of Public Administration, Göteborg, Sweden Senior Lecturer, Director of Research, University West, Department of Nursing, Health and Culture, Trollhättan, Sweden 2 Keywords cooperation, health care, semi-synchronous, teamwork Correspondence Johan M. Berlin School of Public Administration Göteborg University Göteborg Sweden E-mail: johan.berlin@spa.gu.se Accepted for publication: 13 June 2007 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00919.x Abstract Rationale In this article, the difference between team and group is tested empirically. The research question posed is How are teams formed? Three theoretical concepts that distinguish groups from teams are presented: sequentiality, parallelism and synchronicity. The presumption is that groups cooperate sequentially and teams synchronously, while parallel cooperation is a transition between group and team. Methods To answer the question, a longitudinal case study has been made of a trauma team at a university hospital. Data have been collected through interviews and direct observations. Altogether the work of the trauma team has been studied for a period of 5 years (2002–2006). Results The results indicate that two factors are of central importance for the creation of a team. The first is related to its management and the other to the forms of cooperation. To allow for a team to act rapidly and to reduce friction between different members, clear leadership is required. Conclusions The studied team developed cooperation with synchronous elements but never attained a level that corresponds to idealized conceptions of teams. This is used as a basis for challenging ideas that teams are harmonious and free from conflicts and that cooperation takes place without friction. Introduction One of the main challenges for organizational research is defining what a team is and how it is formed. One difficulty has been that the characteristics of a team have rarely been studied as it develops and matures [1]. Therefore ideal descriptions of teams as frictionless, unilaterally harmonious, free of conflicts and goal-oriented have been presented, which have been criticized [2–4]. Conceptions of ideal teams have had a major influence in the public sector. This has found expression not least in organization of the health and medical services, where teams have been regarded as reliable success strategies for opening up conservative and unwieldy organizations [5]. Exploration of the development process from group to team in this study enables critical analysis of whether teams really attains a state of frictionless cooperation. This is undertaken by studying how teams form in extremely short periods. The question posed in this article is therefore How are teams formed? The purpose is to test the difference between group and idealistic assumptions about team forming. To provide an answer to the question posed in the article the trauma team at a Swedish university hospital has been studied closely. The trauma team offers especially interesting conditions in terms of research, particularly as the transition from one phase of cooperation to another can be recorded minute by minute during the team’s intensive activity. This makes it possible to examine different phases of cooperation between the members of the team. Theoretical framework Groups and teams An alternative concept to ‘team’ that is used for entities consisting of individuals is ‘group’. Both the concepts of group and team are not infrequently used without definition and as synonyms [1,6]. Confusion exists because ‘team’ carries the connotation of both sequential cooperation, where the members have minimal interaction, and synchronous cooperation, where the members take advantage of each other’s skills without aspiration of prestige [7]. Procter and Mueller [8] describe how team has developed from a socio-technical tradition in which autonomous groups were considered to have an optimizing effect on organizations. Expressions that can be found in this context are work group, autonomous group and group process. The word ‘group’ is defined as ‘a number of people or things located, gathered, or classed together . . .’ [9]. © 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 14 (2008) 569–576 569 The 20-minute team One difference between the concepts is that a group need not consist of individuals but may just as easily refer to abstract things that are in the same place. However, a team always involves individuals. Another difference between the concepts is that a team is considered to be more focused than a group and to display a greater degree of homogeneity. Team also presupposes the joint action of its members to solve a shared task, which is not always the case for groups [10]. What by definition distinguishes a team from a group is that every member of the team needs to know what is to be achieved jointly [11]. The task should be sufficiently explicit for all the members of the team to understand their own functions and have the scope to take their own initiatives. The tasks should not be susceptible to varying interpretations by the members of the team but easy to focus and agree on [12–15]. Another factor in the formation of a team is that its members are given the scope to function as a team. This makes certain demands when it comes to independence, authorization and the specific composition of the members of the team [16,17]. However, idealized descriptions of teams go one step farther. Here it is maintained that the members of the team have a collective aim, have shared goals and that the members of the team are committed [18]. This contradicts the argument of Cyert and March [19] that individuals have goals while organizations do not. In many cases the goals of an organization are the same as those expressed by its leaders, which need not have any relation to others involved in the organization [3,20]. Katzenbach and Smith [18] claim, however, not only that teams work best when they are clearly demarcated and have clear tasks. They also assert that teams distribute tasks internally and in agreement with each other. Literature dealing specifically with teams in the health and medical services offers similar descriptions. The members of a team are said to devote themselves jointly and simultaneously and in agreement with each other to interrelated tasks. Opie [21] describes how the members of health care teams representing different disciplines jointly assess, treat and examine the caring needs of individuals. Another example is Antoniadis and Videlock [21], who define an efficient health care team as one that displays a relaxed atmosphere while at the same time there are regular discussions between its members, who are eager to listen to each other. It is emphasized that in this type of team differences of opinion and criticism are permitted. They display few hidden agendas and leadership is shared [21,22]. Such ideal descriptions of how teams are formed describe a frictionless interaction between leadership and the members in the team’s development phase. One untested assumption is that teams form spontaneously. Katzenbach and Smith [18] claim that it is enough to assemble a group for a specific task for a team to be created. In other words, teams become teams when a task or a challenge is accepted and approached collectively. A group of individuals with different characters can then move from individual treatment of the task into an intensive phase where there are no considerations of prestige to prevent collective intervention in each other’s tasks to enable joint solution of the problem. Seen in this way, teams should only be organized by offering groups of individuals challenges for them to group around. Autonomy and trust will then guarantee that the participants will act spontaneously and in accord. It is asserted that given the right conditions with regard to the individuals involved, their qualification, the task and the intention, teams will gradually come into being. This 570 J.M. Berlin and E.D. Carlström approach has, however, contributed to the creation of teams that have been teams only in name rather than in how they function. Teams have been constructed, have jointly undertaken a task and then been expected to develop mutual give-and-take with discouraging results. They have turned out to evolve into differentiated groups with internal oppositions whose members develop sequential ways of working and shun the tasks undertaken collectively [4]. Differentiated groups tend to be called ‘teams’, although the members are independent of each other [7]. Katzenbach and Smith [18] also claim that leadership is shared when a team is created. There is a shift from having a nominated leader to a state in which all of its members can exercise control in a spontaneous, not predetermined, alternating leadership. This phenomenon has been confirmed in studies of palliative teams. When the team convenes, its leadership alters informally as various aspects of the patient’s situation are dealt with. When one member can no longer contribute, another member of the team takes over control on the basis of the patient’s needs [23]. In both cases an anti-hierarchical attitude to leadership prevails. The team leader has a passive role and it seems to be able to achieve consensus with all of the members taken into account. Team leadership therefore is said to be supporting rather than leading, and is described by the term team coaching [24]. Here criticism has been expressed by Benders and Van Hootegem [25], who asserts that autonomous teams without leaders that make decisions hardly exist. Nevertheless, the belief in autonomy and the harmonious rotation of leadership survives as an ideal when teams are created. The team terminology has come to overlap the group terminology. This has been criticized by Saltmans et al. [7], who distinguishes between team and group in the fact that team are simultaneous and intersubjective, whereas groups are split up and individual. This study is supported by the definitions mentioned herein as synchronous and sequential. To this we add a mean form which is simultaneous and individual cooperation. This mean form, here called parallel, has been identified as common in acute health care teams [7]. These three forms of cooperation are here suggested to make out a reference frame which will then be used to analyse the trauma team studied within the scope of this study. Sequential cooperation Sequential cooperation comprises a traditional step-by-step working process in which each participant waits for her or his turn to perform a specific task. Sequential cooperation has also been called intra-organizational task division and decentralization [26]. This technique has its roots in scientific management traditions which focus on individual performance and where collective, integrated cooperative methods are considered to lead to free riding and slacking [27]. The definition of team used in this article means that they do not involve sequential methods of working. Organizations with long historical traditions are more than likely, however, to embody fragments of traditional sequential techniques. These administrative relics make it more difficult to establish teams [28]. The health care sector is one that offers examples of organizations in which there are built-in unwieldy administrative processes that sustain a sequential approach to their operation [29]. Good illustrations of this can be found in the Swedish health care system, which is characterized by the predominance of groups. For example, Westrin [30] describes how doctors in the © 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd J.M. Berlin and E.D. Carlström The 20-minute team Sequential Figure 1 From sequential to synchronous forms of cooperation. • Group • Relay-race division Swedish health care system have helped to promote sequential working methods. The most characteristic example is the system of referral, in which specialists take over from each other in the management of patient needs or the patients themselves are transferred from one specialist to another. Holmberg [31] offers a similar description of how health care staff divided into professional, semi-professional and non-professional groups are separated from each other by a sequential organization of their tasks. The distance between the groups is maintained by linguistic and communication barriers and working processes in which each group undertakes its own tasks [31,32]. This kind of situation can also be encountered in groups of staff that describe themselves as teams but which are never able to become more than loosely connected groups that work sequentially. Parallel cooperation A team in which parallel cooperation takes place can succeed in undertaking tasks at the same time but lacks the ability to perform them jointly. This means that the members of the team act as a group, which involves focusing on their own tasks and avoiding consideration of the overall needs, but with the difference that the tasks are performed at the same time. Lind and Skärvad [33] describe parallel cooperation in what they call a role-integrated team. By definition, a role-integrated team is as close to being a group as to being a team. Tasks are divided strictly between the members of the team and the work is undertaken in parallel in a way that makes it impossible for the members of the team to switch positions. The work is standardized on the basis of the different roles allocated to the members. One example of parallel cooperative techniques can be found in the allocation of roles between the different members of the staff in an operating theatre. The aim is to enable the participants to work according to their own professional agendas with clearly defined tasks but that at the same time these should interact seamlessly [34]. Indeed, standardization of tasks, which distinguishes parallel cooperation, has been regarded as both hindering and enabling team creation. Adler & Borys [35] maintain that standardization generally encourages simplified and repeated behaviour that augments conformity instead of stimulating individual thinking and creativity. Another factor contributing to parallel techniques is high workload and stress. A synchronous cooperation can during stress increase an individual focus [36]. Synchronous cooperation Synchronous cooperation is characteristic of the ideal descriptions of teams. This differs from parallel cooperation in that tasks are not only undertaken at the same time but the members of the team swap tasks and cover for each other unhampered by prestige. The members of the team focus not only on their own tasks but they © 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Parallel • Intermediate form • Simultaneous but individual Synchronous • Team • Exchange unaffected by prestige identify needs and weaknesses in the teamwork as a whole by displaying mobility and by rapidly reallocating resources. Savage [37] uses the expression ‘multiplexing’ to describe how the members of a team continually shift focus from one task to another. Similarly, Drucker [38] describes how team cooperation takes place synchronously when the team cuts across traditional demarcation lines. To achieve this, a team needs to coordinate its tasks and at the same time not be bound to comply with a predetermined workflow. In the words of Drucker [38] the music is then created ‘as it is played’. Like Drucker [38], Davis [39] believes that focus is shifting from traditional sequential procedures to the implementation of multiple functions simultaneously. Davis [39] uses the metaphor of holism, which means that a team relates all the elements of a totality to each other in exchanges that are shorn of concerns about prestige. The links and differences between sequential, parallel and synchronous forms of cooperation can be summarized in the diagram below (see Fig. 1). The levels of cooperation described above are important constituents of the empirical systematization in this study and in the ensuing analysis. Methods To provide an answer to the question posed in this article, a case study has been undertaken of a trauma team at a Swedish university hospital. In view of its aim, a trauma team was considered to offer a highly suitable case for study [40]. There are three reasons for the choice of a trauma team as the subject of this study. The first is that the study involved recording how teams are formed on a repeated number of occasions. For this reason, the trauma team, which is convened and disbanded several times each day, could be considered very suitable and appropriate, particularly as the team goes through the procedure (from group to team) every time it is reconvened. Second, it is unusual for a trauma team to consist of the same individuals. The different on-call arrangements in different units mean that the staff involved will vary. As a result the predetermined roles ascribed to the members of the team assume a particularly prominent and controlling function. And third, the trauma team can be seen as one way in which a hospital can break down long-standing patterns of action in order to save time. In this study we have used two methods to collect data. The first of these has consisted of personal interviews. During a 5-year period (2002–2006) we followed and interviewed a number of key figures in the trauma team. The professional categories interviewed belonged to various vocational groups and have comprised assistant nurses, nurses, doctors, team leaders and the team coordinator. Interviewing different categories of staff enabled different points of departure and perspectives to be taken into account. Altogether 30 personal interviews were made during the entire data-collection period (2002–2006) [41–44]. 571 The 20-minute team The second data-collection method consisted of direct observation [45]. In practice, data collection comprised following the trauma team in action in the university hospital’s emergency ward. We have watched the team at work both where emergency treatment was involved and during practice sessions. During the five observation sessions we followed the progress of 10 cases: six genuine patients and four simulated practice situations. These observations were made during a 2-year period, the years 2005–2006. One advantage of the use of direct observation as a method of collecting data is that it is not exposed to the interpretations of intermediaries. As observers, we could ourselves see, hear, appraise and select the relevant data. The two methods, personal interviews and direct observation were considered to supplement each other and these approaches were regarded as highly appropriate for attainment of the purposes of the study. Another argument is that similar approaches have been used in similar studies of surgical teams [34,46]. A thorough description of the initiation, development and maturation of the trauma team is provided below. Results, team work in emergency nursing The trauma team Trauma teams are based on an organizational concept for emergency treatment that has gained widespread international acceptance [7,47]. This method of working began to be implemented at the university hospital in the mid-1990s. The staff who work in the team undergo special training, which is based on a coherent treatment concept according to standardized routines. The trauma team consists of 11–13 individuals who come from different units and represent different professions/specialities. They are activated by an incoming ambulance or alternatively when specific vital criteria for a patient in the hospital drop below a minimum level. If there is an alarm, the team assembles in the emergency unit’s special trauma room. The aim of the team is to identify and remedy as quickly as possible all of the injuries that threaten the life of a patient. A patient’s stay in the emergency unit should be brief [48]. The objective is for treatment not to exceed 20 minutes. This is part of the ‘golden hour’ that should not be exceeded before a patient can be transferred for surgical treatment [49]. The trauma team is dissolved when the patient is transferred for further treatment at one of the hospital’s other units. Initiation Only a few minutes after the alarm has been given, the members of the trauma team assemble outside the emergency unit’s trauma room. They change rapidly into trauma equipment, which hangs in orderly rows outside one of the entrances to the trauma room. Dressed completely in green, their faces concealed behind visors, all that identifies each individual member is their name plate. When the patient arrives everyone in the team unites in a ‘silent minute’. During this period the patient’s condition is reported to the members of the trauma team by the ambulance attendants. Up until this moment nobody in the trauma team has taken any initiative. What happens next has been described by several respondents as decisive for the continued work of the team. If the team leader is to have any influence on the rest of the process, some 572 J.M. Berlin and E.D. Carlström indication is required of her or his leadership position. If the team leader fails initially to take over leadership, there is a risk of conflict, which can lead to the creation of turbulence in the team. In the interviews the respondents stated that in principle there could be two outcomes if the team leader failed to establish initial control of the team. To begin with there was a risk that a new competing leader would emerge, who had suggestions about what the team should do. If the new leader was distinct and took initial initiatives, certain members of the team could shift leadership focus and begin to act according to the new leader’s orders. Second, there was a risk that several new potential leaders would make suggestions about the future course of action. This led to confusion and discussion which would result in delay. The anaesthetics staffs are described by the respondents as the main competitors to the team leader. They are considered to have the expertise to take command and direct people in emergency situations and were therefore prone to assume leadership. This was made clear during one of our direct observation sessions. On this occasion the surgeon was examining a badly injured patient. The surgeon said very little and the anaesthetist felt that he was acting too slowly and ineptly. The situation also showed that the team leader did not take the initiative to establish active control but adopted the role of a passive spectator. During the surgeon’s examination of the patient, the anaesthetist has been watching impatiently. Now he begins to ask the patient questions – ‘What’s your name?’ ‘What year were you born in?’ The patient answers the questions, upon which the anaesthetist turns to the team leader and says ‘He has said what his name is, at least’. During this time the surgeon had moved from the foot of the bed to the patient’s right. Everyone is waiting for the team leader to take the initiative but instead the anaesthetist shouts ‘Everyone ready, turn him over?’ ‘OK, let’s turn him over.’ The team turns the patient over – on the command – and the surgeon examines his back. The team leader looks on passively. (Observation trauma alarm) In the example above, the anaesthetist took over the role of both the surgeon and the team leader. He anticipated decisions and directed the actions of the team without either the surgeon or the team leader protesting. The team smartly followed the anaesthetist’s orders and the work proceeded. From there on the anaesthetist exerted a dominant influence on the team. The members of the team exchange amused glances. When the team leader gives the team orders, the team glances quickly at the anaesthetist, who from now on has an implicit ‘superordinate veto’ and endorses the words of the team leader with a glance. (Observation trauma alarm) In the interviews the respondents described how a team leader who sets explicit limits can succeed in regaining the initiative from an anaesthetist who tries to assume responsibility. This helps to restore the team’s cohesion. Its members, including the member who challenged the team leader, back down and conform so that the work around the patient can proceed. Development and maturity The ways in which the trauma team cooperated could differ with different emergencies. In certain emergencies, the members of the © 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd J.M. Berlin and E.D. Carlström trauma team acted as if the others were not there. On other occasions, the team proceeded from caution during an initial stage while the members got to know each other to the phase in which they started to assist each other. This did not take place, however, without the team being held in a ‘tight rein’ by the team leader. One reason for this was the parallel method of working that characterized their activities. During the interviews the respondents were given a chance to reflect on how the way in which the team cooperated developed (sequential, parallel, synchronous). The respondents claimed with few exceptions that their cooperation was on the whole parallel. Parallel working methods require clear direction, partly to follow the predetermined flow of the procedures and also to set priorities for more or less important tasks. The team leader therefore governs the sequence of activities by giving orders to the members of the team, who were either told to act or wait. The team leader played a central role in coordinating the different procedures undertaken around the patient. The team leader’s management of the team contributed to its development. During this stage, however, it could happen that the members of the team gradually identified the way in which the others were working. Gradually awareness evolved in the team and between different members. A pattern of action emerged with some of the team spontaneously and without directions from the team leader ‘holding back’ while other ‘acted’. In addition, others could recognize requirements and either assisted or allowed themselves to be assisted across professional boundary lines. The respondents described the establishment of the team as a state when fundamentally the parallel working methods continued but there were synchronous elements. This could be perceived during observation of teams after they had passed the initial stage of parallel techniques. The following notes made during observation illustrate the situation described. Both anaesthetists have been assisted by the neurosurgeon. He has stretched his arm round one of the anaesthetists to grasp the ventilation balloon and is now ventilating the patient . . . The trauma nurse inserts her needle, stopping the flow with a thumb on the patient’s lower arm. She removes the sleeve and shouts ‘PVC 2.0 set in right arm’, which is noted by the secretary. Both of her hands are occupied. The anaesthetics nurse has moved around the bed and also at the same moment rolled forward the sample trolley, and is now squatting together with the trauma nurse passing her test tube after test tube . . . One of the assistant nurses sees an ambulance orderly behind her back and asks him to fetch some scissors. The orderly glances round and the assistant nurse points to a table behind the secretary where the scissors are lying. He gives her the scissors and she begins cutting off the patient’s garments. (Observation trauma alarm) The synchronous elements mean that the role of the team leader changes. Procedures still follow the predetermined flow with the team leader directing when needed, but the team does not require the same degree of control as before. As the team established itself, the need to maintain the order diminished. The rules do not need to be shouted out. When dividing lines were crossed, this took place with consideration and in mutual understanding. Boundary lines that either could not or should not be disregarded were respected. © 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd The 20-minute team Both waiting time and the risk of conflict were reduced. One team leader claimed that in this state the group worked like a ‘body’. Those elements of teams that consisted of members who routinely worked together could already display this kind of behaviour in the initial stages, while the team as a whole did not exhibit elements of synchronicity until cooperation had been taking place for a number of minutes. However, there were occasions when no synchronous elements appeared during the work of a trauma team. This could be owing to the team leader’s inability to perceive that the team was developing synchronous cooperation and therefore was not prepared to ‘let go of the reins’. The respondent’s description illustrates how a team leader controlled the team even though its members had identified adaptable forms of cooperation. An inflexible team leader ‘stuck to his guns’ by failing to tone down his role when the team was dealing with its tasks sequentially. Discussion In the empirical description it can clearly be seen that the trauma team cuts across the traditional forms of cooperation that prevail in the hospital. Earlier working methods, when one member of the staff takes over from another, have been replaced by forms of simultaneous cooperation. The aim is to recast the intraorganizational role allocation that previously characterized working methods in health care in order to establish an organization that is capable of taking action without delay. The question we posed initially was How are teams formed? Our empirical description shows that two factors play a central role when teams are established. One relates to the forms of cooperation in the team and the other to its leadership. It turns out that these two factors interact. Parallel forms of cooperation demand clear leadership and the way in which leadership was provided contributed to the formation of the team. These factors are important as the aim of the trauma team is to undertake in a very short space of time procedures that can save patients’ lives and offer a stable platform for continued treatment. How they are directed turned out to play a decisive role in reducing friction between the members of the team. Forms of cooperation and leadership The logic of sequential action is firmly established in health care. Although the aim was to abandon sequential logic, this still did not happen in the teams. The sequential system of working survives in the individual plans of action of the members of the team. The only difference is that they carry out their tasks at the same time, which has been defined here as parallel cooperation and which means that the members of the team adopt their given positions and follow a standardized pattern of action that is based on predetermined roles. Parallel cooperation is a half-way stage between sequential and synchronous cooperation and in the context of trauma has the advantage of enabling treatment time to be reduced. The disadvantage is that the members of the team find it difficult to see what the others are doing and cover for each other [50]. This can be compensated for by firm direction from the team leader in managing competing interests around the patient. The team leader forms an important link in directing and coordinating the parallel procedures. Inadequacy on the part of the team leader will create 573 The 20-minute team J.M. Berlin and E.D. Carlström hesitation in the team and instead their actions will be directed by their professional logic, which will result in uneven and inflexible treatment of the trauma. However, on certain occasions the team underwent a further stage of development by displaying synchronous elements in their cooperation. This means that they looked around, noticed both needs and resources that were not being used and communicated with each other. Synchronous cooperation is characterized by mobility and the ability to reallocate resources rapidly [51]. This, however, required two conditions to be fulfilled. One is that the members of the team could see the totality of needs and resources in the team and exploit possibilities of making reallocation. The second is for the team leader to tone down his own role when a synchronous technique develops. Regulation by a team leader who did not alter management approach when the team displayed elements of synchronicity could eliminate the spontaneous interactions initiated by members of the team and therefore inhibits synchronous development. On the other hand the team leader could not release control completely and stop directing the team as the influence of sequential logic still survived even after synchronous elements had developed. Teams therefore never became entirely synchronous. Their members continued to act on the basis of their own individual plans of action and the team leader was still needed to regulate their input and the order in which they took place. The difficulty was at the same time observing and taking into account the synchronous elements that had been established in the team. This way of working can be described as semisynchronous cooperation, in that the team displayed a mixture between parallel and synchronous cooperation. The two factors that jeopardized the ability of the team to attain a semisynchronous approach were the team leader’s ability to direct the process and internal competition for leadership. If the team leader was able to provide direction to eliminate internal competition for leadership, conditions prevailed to permit the development of semi-synchronous methods through the reduction of prestige concerns and uncertainties during the trauma treatment process [52]. The theoretical model presented earlier in this paper therefore needs to be extended by the addition of semi-synchronous cooperation and there is thus a difference in the management of the team between the two forms of cooperation. Traditional sequential techniques do not require the presence of leadership as the work follows routines in which tasks are handed over like the baton in a relay race. In health care this normally takes the form of referrals and unwieldy delegation routines. In the opposite, in other words, synchronous models, the presence of an official manager is not Sequential • Group • Relay-race division • Management need not be present, routines regulate cooperation Parallel • Intermediate form • Simultaneous but individual • Requires active on-the-spot regulation and leadership Semi-synchronous • Intermediate form • Team under development • Requires on-thespot leadership that can avoid eliminating synchronic elements through over direction required either, as the teams will transfer leadership to the member best suited to exercise it any moment with no concern about prestige. However, the two intermediate forms, parallel and semisynchronous cooperation require active management. Parallel forms demand constant direction by an explicit leader and semisynchronous cooperation makes even greater leadership demands, as then it is question of a leader with an active directive role who is also, at the same time, prepared to ‘back down’ to avoid precluding elements of synchronous cooperation. If an ideal team can be expected to cooperate synchronously and parallel cooperation is an intermediary stage between group and team, semisynchronous cooperation could characterize the development of a team. Theoretical development In conclusion there are grounds for returning to the question posed in our research: How are teams formed? One stage in responding to this question is to return to and supplement the theoretical diagram presented in the introduction. The previous diagram has been supplemented with the semi-synchronous form of cooperation (see Fig. 2). This diagram illustrates how the team in the study moves from parallel forms of cooperation to semi-synchronous ones. The team embodies remnants of sequential logic but never attains the ideal synchronicity of a team. This also constitutes the answer to the research question. Another contribution is the observation of the role of the team leader. Neither sequential nor synchronous techniques require the presence of any official leader, as in the first case cooperation is regulated by routines and in the latter by the spontaneous allocation of tasks between the members of the team unhampered by prestige. On the other hand, the two intermediary forms, ‘parallel’ and ‘semi-synchronous’, require on-the-spot and active management. Where parallel cooperation is involved, the team leader’s control is intended to set priorities between the different courses of action and avoid competition. Semisynchronous cooperation requires the leader to adopt an actively directive role while remaining at the same time ready to allow the team to work independently when it develops synchronous features. This gives us reason to propose a definition of a team that has a broader meaning than the idealized conception; a team is a limited number of individuals who cooperate above a sequential level. This definition differs not only from the idealized definition of a team but also those based on empirical studies. The concepts of limited and sequential presuppose that a team does not consist Synchronous • Team • Exchange unhampered by prestige • Requires no official manager, leadership rotates spontaneously Figure 2 Forms taken by teamwork. 574 © 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd J.M. Berlin and E.D. Carlström of totally differentiated organizations or units [2]. The definition also requires cooperation above a sequential level, which means that the team works in parallel but not necessarily synchronously or without needing leadership [53–55]. In effect, the definition has only one purpose, which is to differentiate a team from a group. Given any more specifically idealized definition of team, the concept of group becomes even more evasive and the concept of team more unattainable. The effect of such a definition will merely widen the gap between theoretical assumptions about teams and how the term is viewed pragmatically. The ideal synchronous cooperation of the kind that occurs in Katzenbach and Smith’s [18] depiction is probably never attained for more than brief periods of teamwork. Tasks are not allocated without friction. This is because it is unrealistic to expect a state of complete shared internal understanding in a team. Nor does this imply the opposite, i.e. a team that does not attain a level of synchronous cooperation is merely implementing traditional sequential techniques. There are patently a number of intermediate forms. One reasonable assumption is that intermediary forms can also be found in teams other than the trauma team. Conclusion It can be seen that the members of the team in this study possess the prerequisites for the development of semi-synchronous forms of cooperation and that it is dependent on a firm leader. There is, however, scope for further descriptions of deviations from the theoretical team ideal. Obviously these deviations can be described specifically in teams that work against the clock and are required to make rapid decisions, act quickly and achieve results. The trauma team has helped to reduce lead times, which can mean the difference between life and death for individual patients. The team overcomes obstacles that exist between professional, specialization and clinical domains and does not comply with earlier sequential working methods and this has turned out to lead to the elimination of delays [56]. Despite certain dissent, the team succeeds in carrying out its task. However, research needs to be made on other teams to examine how far the results of this study can be generalized. The trauma team turned out to be an appropriate subject of study, as it worked with a well-defined task in a restricted area for a short time, which enabled observation of its development minute by minute. It is not, however, self-evident that a team that operates for a longer period with less dramatic tasks is not dependent on its leadership or develops frictionless forms of cooperation [57]. For this reason analyses are required of the interactions between members of teams that cooperate for longer periods [58]. One hypothesis for continued studies is that the findings shown here can also be found in teams that operate in different settings. References 1. Gersick, J. G. (1988) Time and transition in work teams: toward a new model of group development. Academy of Management Journal, 31 (1), 9–41. 2. Mueller, F. (1994) Teams between hierarchy and commitment: change strategies and the ‘internal environment’. Journal of Management Studies, 3 (3), 383–403. 3. Berry, A. J., Broadbent, J. & Otley, D. (1995) Management Control. Theories, Issues and Practises. London: Macmillan Press LTD. © 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd The 20-minute team 4. Church, A. H. (1998) From both sides now: the power of teamwork – fact or fiction? Team Performance Management, 4 (2), 42–52. 5. Berlin, J. & Carlström, E. (2006) Traumateam – förenklat flöde eller försvårande hinder? I: Hälso- och sjukvårdens ekonomi och logistik. En sammanställning av forsknings och utvecklingsprojekt vid Göteborg universitet, Chalmers tekniska högskola, Nordiska högskolan för folkhälsovetenskap och Västra Götalandsregionen. Göteborg: Göteborgs Universitet. 6. Schouteten, R. (2004) Group work in a Dutch home care organization: does it improve the quality of working life? International Journal of Health Planning and Management., 19, 179–194. 7. Saltman, D. C., O’Dea, N. A., Farmer, J., Rosen, G. & Kidd, M. R. (2007) Groups or teams in health care: finding the best fit. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13, 55–60. 8. Procter, S. & Mueller, F. (2000) Teamworking. London: MacMillan Press LTD. 9. Oxford University Press. (2006) The Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10. Desombre, T. & Ingram, H. (1999) Teamwork: comparing academic and practitioners’ perceptions. Team Performance Management, 5 (1), 16–22. 11. Walton, R. E. (1985) Toward a strategy of eliciting employee commitment based on policies of mutuality. In HRM Trends and Challenges (eds R. E. Walton & P. R. Lawrence), pp. 30–53. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 12. Senge, P. M. (1990) The Fifth Discipline. The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency. 13. Drucker, P. F. (1988) The coming of the new organization. Harvard Business Review, 66 (5), 45–53. 14. Galbraith, J. R. & Lawler, E. E. (eds) (1993) Organizing for the Future. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. 15. Hammer, M. (1995) The Reengineering Revolution. London: Harper Collins. 16. Partington, D. & Harris, H. (1999) Team role balance and team performance: an empirical study. Journal of Management Development, 18 (8), 694–705. 17. Prichard, J. S. & Stanton, N. A. (1999) Testing Belbin’s team role theory of effective groups. Journal of Management Development, 18 (8), 652–665. 18. Katzenbach, J. R. & Smith, D. K. (1993) The Wisdom of Teams. Creating the High-Performance Organization. London: Harvard Business School Press/The McGraw-Hill Companies. 19. Cyert, R. M. & March, J. G. (1963) A Behavioural Theory of the Firm. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall. 20. Anthony, R. N. (1988) The Management Control Function. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 21. Opie, A. (1997) Effective team work in health care: a review of issues discussed in recent research literature. Health Care Analysis, 5 (1), 62–73. 22. Antoniadis, A. & Videlock, J. (1991) In search of teamwork: a transactional approach to team functioning. The Transdisciplinary Journal, 1 (2), 157–167. 23. Davison, G. & Hyland, P. (2002) Palliative care teams and organisational capability. Team Performance Management – an International Journal, 8 (3/4), 60–67. 24. Hackman, J. R. & Wageman, R. (2005) A theory of team coaching. Academy of Management Review, 30 (2), 269–287. 25. Benders, J. & Van Hootegem, G. (1999) Teams and their contextmoving the team discussion beyond existing dichotomies. Journal of Management Studies, 36 (5), 609–628. 26. Axelsson, R. (2000) The organizational pendulum: healthcare management in Sweden 1865–1998. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 28, 47–53. 27. Steijn, B. (2001) Work systems, quality of working life and attitudes of workers: an empirical study towards the effects of team and 575 The 20-minute team 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 576 non-teamwork. New Technology, Work and Employment, 16 (3), 191– 203. Vallas, P. V. (2003) Why teamwork fails: obstacles to workplace change in four manufacturing plants. American Sociological Review, 68 (2), 223–250. Nylén, U. (2005) Coping with Trinity: Human Service Professionals in Interorganisational Team Work. Unpublished paper presented at the 18th Scandinavian Academy of Management Meeting 18th-20th August 2005. Aarhus, Denmark. Westrin, C.-G. (1996) Juridik och medicin. Några funderingar runt ett angeläget forskningsfält i 35 års utredande: en vänbok till Erland Aspelin. Malmö: Departementets utredningsavdelning. Holmberg, L. (1997) Health-Care Processes. A Study of Medical Problem-Solving in the Swedish Health-Care Organisation. Lund: Lund University Press. Forsberg, E., Axelsson, R. & Arnets, B. (2001) Effects of performance-based reimbursement on the professional autonomy and power of physicians and the quality of care. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 16, 297–310. Lind, J.-I. & Skärvad, P.-H. (1998) Nya Team i Organisationernas Värld. Malmö: Liber Ekonomi. Edmondson, A. C. (2003) Speaking up in the operating room: how team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40 (6), 1419–1452. Adler, P. S. & Borys, B. (1996) Two types of bureaucracy: enabling and coercive. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41 (1), 61–89. Driskell, J. E., Salas, E. & Johnston, J. (1999) Does stress lead to a loss of team perspective? Group-Dynamics, 3 (4), 291–230. Savage, C. M. (1996) 5th Generation Management. Oxford: Butterworth/Heinemann Limited. Drucker, P. F. (1992) Managing for the Future. Oxford: ButterworthHeinemann. Davis, S. M. (1982) Futurum Exaktum. Borgå: Werner Söderström. Yin, R. (1994) Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 2nd edn. London: Sage. Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989) Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 532–550. Kvale, S. (1996) Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Alvesson, M. & Deetz, S. (2000) Doing Critical Management Research. London: Sage. J.M. Berlin and E.D. Carlström 44. Rubin, I. S. & Rubin, H. J. (2004) Qualitative Interviewing: the Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 45. Burgess, R. G. (1991) In The Field – an Introduction to Field Research. London: Routledge. 46. Edmondson, A. C., Bohmer, R. M. & Pisano, G. S. (2001) Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46 (4), 685–716. 47. Colet, E. & Crichton, N. (2006) The culture of a trauma team in relation to human factors. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 1257– 1266. 48. Cooke, W. M. (1999) How much to do at the accident scene? Spend time on the essentials, save lives. British Medical Journal, 319, 1150– 1150. 49. McSwain, N. E., Jr (ed.) (1999) PHTLS. Basic and Advanced Prehospital Trauma Life Support. St. Louis, MO: Mosby. 50. Shabnam, U., Sevdalis, N., Healey, A. N., Darzi, A. & Vincent, C. A. (2006) Teamwork in the operating theatre: cohesion or confusion? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 12 (2), 182–189. 51. Dyck, B., Starke, F. A., Mischke, G. A. & Mauws, M. (2005) Learning to build a car: an empirical investigation of organizational learning. Journal of Management Studies, 42 (2), 387–416. 52. Klein, J. K., Ziegert, J. C., Knight, A. P. & Xiao, Y. (2006) Dynamic delegation: shared, hierarchical, and deindividualized leadership in extreme action teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 590– 621. 53. Buchanan, D. (1987) Job enrichment is dead: long live high performance work design. Personnel Management, May, 40–43. 54. Grayson, D. (1991) Self-regulating work groups – an aspect of organisational change. International Journal of Manpower, 12 (1), 22–29. 55. Pfeffer, J. (1998) The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 56. Ali, J. (1998) Effect of basic prehospital trauma life support program on cognitive and trauma management skills. World Journal of Surgery, 22, 1192–1196. 57. Brass, D. J. (1984) Being in the right place: a structural analysis of individual influence in an organization. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29 (4), 518–539. 58. Aritzeta, A., Swailes, S. & Senior, B. (2007) Belbin’s team role model: development, validity and applications for team building. Journal of Management Studies, 44 (1), 96–118. © 2008 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd