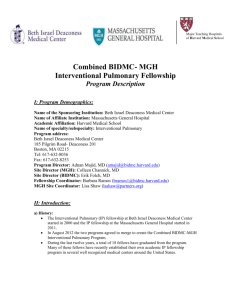

Hospital Quality: Ingredients for Success: A Case Study of Beth

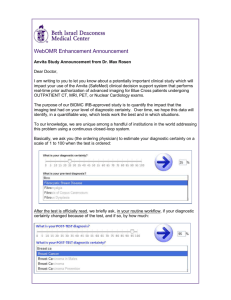

advertisement