Autonomy- vs. connectedness-oriented parenting behaviours in

advertisement

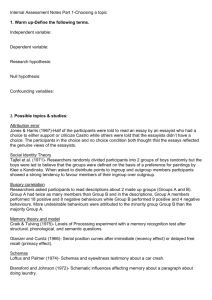

International Journal of Behavioral Development 2005, 29 (6), 489–495 # 2005 The International Society for the Study of Behavioural Development http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/pp/01650254.html DOI: 10.1080/01650250500147063 Autonomy- vs. connectedness-oriented parenting behaviours in Chinese and Canadian mothers Mowei Liua, Xinyin Chenb, Kenneth H. Rubinc, Shujie Zhengd, Liying Cuie, Dan Lie, Huichang Chenf, and Li Wangg The purpose of the study was to investigate maternal socialization goal-oriented behaviours in Chinese and Canadian mothers. Participants were samples of children at 2 years of age and their mothers in P.R. China and Canada. Data on child autonomy and connectedness and maternal encouragement of autonomy and connectedness were collected from observations of mother–child interactions in a laboratory situation. Cross-cultural similarities as well as differences were found in the study. Chinese mothers had higher scores on overall involvement than Canadian mothers during mother–child interaction. When overall involvement was controlled, Chinese mothers had higher scores than Canadian mothers on encouragement of connectedness. In contrast, Canadian mothers had higher scores than Chinese mothers on encouragement of autonomy. The results suggest that culturally general and specific socialization goals and values are reflected in maternal parenting behaviours. Introduction a Trent University, Peterborough, Canada; b University of Western Ontario, London, Canada; c University of Maryland, College Park, USA; d Inner-Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China; e Shanghai Teachers’ University, China; f Beijing Normal University, China; g Peking University, Beijing, China. authoritative and authoritarian styles. Although findings about the broad categories are helpful for us to discern general features of parenting in Chinese culture, they may provide little information about the processes that account for the effects of parenting on child behaviours (Parke & Buriel, 1998). To acquire an in-depth understanding of Chinese parenting, it is essential to examine specific dimensions or ‘‘components’’ (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Second, most of the studies focus on parents’ self-reports of their child-rearing beliefs and attitudes. Whereas parental child-rearing beliefs and attitudes are important to consider, their relations with parental behaviours are not straightforward. According to Sigel (1985), it may be simplistic to expect that a one-to-one correspondence between attitudes and behaviours will explain the ‘‘mental steps leading to the expression of intended action.’’ The magnitude of the attitude–behaviour association is modest at best (e.g., Kochanska, Kuczynski, & Radke-Yarrow, 1989), suggesting that parental attitudes may not necessarily be reflected in parenting behaviour. Conceptually, parental behaviour in parent–child interactions is a more proximal and direct predictor of child behaviour (Belsky, 1984; Rubin & Burgess, 2002). Parental behaviour may be influenced by cultural values and, at the same time, may have a direct bearing on child behaviour. Third, although many cross-cultural researchers have recognized the importance of the general cultural background for socialization, much existing research is ‘‘context-free’’ because little attention has been paid to specific aspects of parenting behaviours that are relevant to cultural beliefs and socialization goals. For example, although Chinese parents have been found to be more authoritarian than Western Correspondence should be sent to either Mowei Liu, Department of Psychology, Otonabee College, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada K9J 7B8; e-mail: moweiliu@trentu.ca; or Xinyin Chen, Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada N6A 5C2; e-mail: xchen@uwo.ca. The research described herein was supported by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and by a Scholars Award from the William T. Grant Foundation to Xinyin Chen. We are grateful to the children and parents for their participation. Developmental and cross-cultural researchers have long been interested in socialization patterns in different societies (e.g., LeVine, Miller, & West, 1988). During the past 15 years, for example, a number of researchers have compared parenting styles and practices in Chinese and North American parents. For the most part, these researchers have relied on Baumrind’s framework for the conceptualization and categorization of socialization practices (e.g., authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive styles; Chao, 1994; Chen et al., 1998; Dornbusch, Ritter, Leiderman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987; Wu et al., 2002). Generally, Chinese parents have been described as more authoritarian than North American parents (Steinberg, Dornbusch, & Brown, 1992). It has been found that compared with their Western counterparts, Chinese parents tend to endorse the use of coercive and high-power parenting and emphasize child obedience (e.g., Chao, 1994; Chen et al., 1998; Dornbusch et al., 1987; Lin & Fu, 1990). Moreover, Chinese parents are less likely than North American parents to use democratic, authoritative styles in child-rearing (e.g., Chao, 1994; Dornbusch et al., 1987). Several theoretical and methodological weaknesses limit current research on Chinese parenting. First, researchers have focused mostly on such broad categories of parenting as 490 LIU ET AL. / MATERNAL PARENTING BEHAVIOURS parents, it is unclear why Chinese and Western parents use particular parenting styles. Is there a logical connection between such cultural values as a collectivistic orientation and authoritarian parenting styles? Might it be that authoritarian parenting helps achieve specific socialization outcomes in Chinese culture? The question may be difficult to answer given that the association between general cultural beliefs and socialization practices is rather complicated. In the present study, we attempted to investigate parenting behaviours that are directly associated with specific cultural values, particularly those relevant to socialization goals, in Chinese and Canadian mothers. By identifying and examining parental behaviours that reflect socialization goals, a better understanding of the involvement of the cultural context in the processes of human development may be acquired. Anthropologists and psychologists have been interested in two basic developmental scripts in terms of the endpoints that individuals are socialized to meet; one is concerned with individual autonomy or independence and the other with connectedness or interdependence (e.g., Greenfield, 1994; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1989). The primary goal of the socialization of autonomy is to help children to become self-reliant individuals who enter ‘‘into social relationships and responsibilities by personal choice’’ (Greenfield & Suzuki, 1998). In contrast, the connectedness goal is to socialize children to be embedded in a network of relationships and social responsibilities, with an emphasis on personal achievement in the service of a collective such as the family (Greenfield & Suzuki, 1998). Cultural values pertaining to personal autonomy or independence are traditionally viewed as a part of individualism—a construct that encourages privacy, autonomy, and the freedom of the individual (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002; Triandis, 1989). From a developmental perspective, socializing agents focus on the individual as the ‘‘unit of experience’’ and on ‘‘becoming one’s own person’’ (Larson, 1999; Triandis, 1990). Consistently, the role of parents is to help children acquire self-sufficiency, self-direction, and decisionmaking abilities. In contrast, the socialization goal of connectedness is consistent with an orientation that encourages responsibilities to the group and others and respect for authority (e.g., Oyserman et al., 2002). Therefore, the role of parents is to ensure that their child-rearing efforts are conducive to the development of compliance and cooperation. Children are expected to develop a sense of affiliation and learn the skills to cooperate with others (Greenfield & Suzuki, 1998). It should be noted that many current theorists and researchers hold less dichotomous views on culture and development (e.g., Miller, 2002). It is generally believed that both autonomy and connectedness are important developmental goals in most cultures. Thus, parental behaviours oriented to both autonomy and connectedness should be observed within any given culture to a greater or lesser degree. Nevertheless, given the distinct belief systems concerning socialization in Chinese and Western cultures, it would seem important to examine the relative prevalence of autonomy- and connectedness-oriented parenting behaviours; this might allow a better understanding of the common and specific socialization conditions for Chinese and Western children and the cultural involvement in the process of individual development. The present study In the present study, we attempted to explore, from a crosscultural perspective, socialization goal-relevant parenting behaviours in Canadian and Chinese mothers. Samples of children at 2 years of age, and their mothers, in Beijing, P.R. China, and Southern Ontario, Canada, were selected for the study. Information on maternal and child behaviours was obtained from observations of mother–child interactions in a laboratory situation. Based on the literature (e.g., Greenfield & Suzuki, 1998), we were interested in two socialization goal-oriented behaviours: encouragement of autonomy and encouragement of connectedness. Autonomy is often viewed as being derived from the need to act independently of others or to follow one’s inner interests (self-determination and self-governance) (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1985; Gough & Heilbrun, 1983; Hodgins, Koestner, & Duncan, 1996; Jackson, 1984). In the present study, we focused on the child’s attempt to explore the environment as a behavioural manifestation of underlying motives to seek independence and self-governance. Accordingly, parental encouragement of autonomy was indicated mainly by parental behaviours that serve to promote the child’s engagement of autonomous and exploratory activities. Connectedness taps the need for social belongingness and intimacy, as reflected in the tendency to be affiliated with, or maintain social contact with, others (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). In the present study, engaging in a common activity, seeking emotional closeness, and maintaining physical proximity were considered major indicators of the child’s underlying motivation to maintain connectedness with the mother. Accordingly, parental encouragement of connectedness refers to parental behaviours that serve to promote the child’s relationship, connectedness, and affiliation. Based on the argument that children’s autonomy, such as self-initiation, is not as valued in Chinese society as in the West (Ho, 1986), we first hypothesized that Chinese children would have lower scores on autonomy than Canadian children. In contrast, given that Chinese cultural values such as filial piety and group harmony emphasize compliance, cooperation and interpersonal relationships, we hypothesized that Chinese children would have higher scores on connectedness than Canadian children. Accordingly, we expected that cultural differences would be reflected in maternal socialization goaloriented behaviours. Specifically, we hypothesized that Canadian mothers would be more likely to encourage their children to display assertive and independent behaviours. In contrast, Chinese parents would be more likely than their Canadian counterparts to encourage child connectedness. Method Participants Participants in the study were 110 toddlers (50 boys, 60 girls) and their mothers in Beijing, P.R. China, and 102 toddlers (51 boys, 51 girls) and their mothers in Southern Ontario, Canada. The participants in the Chinese sample were recruited through local birth registration offices. The average age was 24.72 months (SD ¼ 1.98 months) for the children and 29.97 years (SD ¼ 2.97 years, ranging from 24–39) for the mothers. The INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BEHAVIORAL DEVELOPMENT, 2005, 29 (6), 489–495 participants in the Canadian sample were recruited through newspaper birth announcements. The average age was 25.06 months (SD ¼ 1.18 months) for the children and 31.05 years (SD ¼ 4.10 years, ranging from 23–41) for the mothers. In the Chinese sample, 45% of the children were from families in which parents were workers; the other 55% of the children were from families in which one or both of the parents were teachers, doctors, secretaries, accountants, or civil officials. Thirty-nine per cent of mothers had an educational level of high school or below high school, and 61% of mothers had a vocational school, college, or university education. Of the children, 38% had out-of-home daycare experience (attending daycare for 10 hours or more per week for 6 months). All children were only children in the family. Like other demographic variables, the only-child phenomenon has been an integral part of the sociocultural background for child development in contemporary Chinese society. For the Canadian sample, all participants were Caucasian, except for three mothers who did not indicate ethnicity. Of the mothers, 46% had no out-of-home jobs. Among the working mothers, 71% were teachers, doctors, secretaries, accountants, or civil officials. Thirty-one per cent of mothers had no more than a high school education; 69% of mothers had a college, university, or post-graduate education. Twenty-eight per cent of the children had out-of-home daycare experience. Twentyeight per cent of the children were only children in the family, and 19% were first-borns. Most of the remaining 53% were second- or third-borns in the family (two were the fourth child in the family, one was the fifth, and one was the sixth). Nonsignificant differences were found in both samples between children and mothers from the different types of families on the variables in the study. The two randomly selected samples were representative of the urban population of toddlers in each country. Procedure Data for the present study were drawn from a larger crosscultural project (e.g., Chen et al., 1998). Mothers and toddlers were invited to visit the university laboratory within 3 months of each child’s second birthday. During the visit, each toddler– mother dyad entered a room with one large chair, one small chair, a low table, and an assortment of toys. The visit started with a 10-minute free-play session, followed by a series of sessions assessing the child’s reactions to various challenging tasks such as inhibition and frustration tolerance. The free-play session was of particular interest in the present study, because it was expected to induce the most naturalistic mother–child interactions without any experimental intervention. Child behaviours and parental goal-oriented behaviours were coded based on the free-play session. The administration of the laboratory sessions was conducted by the authors, as well as by graduate and senior undergraduate students. Identical procedures, including the toys in the session (mostly made in China and purchased in Canada), were used in China and Canada, with detailed instructions concerning preparatory activities and the formal session in the study. The researchers were trained following the same procedures. Written consent was obtained from all parents. All laboratory sessions were videotaped through a oneway mirror and coded in Canada. Data for the Chinese sample were coded by two Chinese graduate students, and the data for the Canadian sample were coded by a senior undergraduate 491 student in psychology. All coders were trained by the first author, following the same procedure. Data coding Child behaviours. Child behaviours were coded using a coding scheme developed by the authors. An event-sampling or episodic approach was used in this study, as suggested by other researchers (e.g., Kucyzynski & Kochanska, 1990). Child behaviours were coded into two broad categories: autonomy and connectedness. At the operational level, autonomy was defined as a child’s self-initiated/self-propelled purposive and independent exploration. Scores of child autonomy included (a) the frequency of child’s initiations of autonomous activities (e.g., explore the environment, play with toys independently, initiate own activities), and (b) the amount of time (in seconds) in which child engaged in independent activities. Connectedness was defined as child’s effort to affiliate/connect with his/ her mother. Specifically, scores of connectedness included (a) the frequency of child’s initiations of connectedness, including initiation of cooperation, expression of emotional closeness, and physical/behavioural proximity to the mother (e.g., invite mother to play, kiss or hug mother, physically approach mother), and (b) the amount of time (in seconds) in which child stayed with and/or engaged in common activities with the mother. Inter-observer reliabilities were calculated based on 20 randomly selected dyads for each sample (approximately 20%). Inter-rater agreement (Cohen’s k) was .91 and .86 in the Chinese sample and .91 and .88 in the Canadian sample, for child’s initiation of autonomous activities and connectedness, respectively. Reliabilities for the durations were calculated based on the agreement and disagreement on the total number of seconds. In addition, correlations between the coders were calculated. Inter-rater agreement was 86% and 85% (r ¼ .97 and .92) in the Chinese sample and 81% and 86% (r ¼ .92 and .95) in the Canadian sample, for the duration of autonomous activities and connectedness, respectively. Socialization goal-oriented maternal behaviours. Maternal encouragement of autonomy and encouragement of connectedness were coded using an event sampling or episodic approach. Maternal encouragement of autonomy included maternal behaviours that served to promote the child’s initiation and exploration. It was indexed by the frequency of maternal behaviours that supported the child’s initiation (e.g., When mother and child enter the room, the mother says, ‘‘Wow, there are so many toys for you to play with. Why don’t you go ahead and play?’’; ‘‘Would you like to play with the bunny by yourself?’’) or continuation (e.g., When a child is playing with a dump truck, the mother says, ‘‘You have done a wonderful job, keep working on it’’; ‘‘That’s amazing, keep going!’’) of selfdirected activities. Maternal encouragement of connectedness included maternal behaviours that served to promote the child’s connectedness and affiliation. Corresponding to child connectedness-related behaviour, maternal encouragement of connectedness was indexed by the frequency of maternal behaviours that supported the child’s cooperation, emotional closeness/communication, and physical/behavioural proximity (e.g., ‘‘Do you want to build the house together with Mom?’’; When a child is playing with the telephone, mother says, ‘‘How about giving Mommy (daddy, or other people) a call’’; ‘‘Bring the truck over, and play near Mommy’’). Inter-rater agreement 492 LIU ET AL. / MATERNAL PARENTING BEHAVIOURS (Cohen’s k) was .91 and .85 in the Chinese sample and .86 and .81 in the Canadian sample for maternal encouragement of autonomy and maternal encouragement of connectedness, respectively. Results Comparisons across cultures on child behaviours A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to assess whether there were country (China and Canada) and sex differences in child autonomy and connectedness. A significant multivariate main effect was obtained for country, Wilks ¼ .67, F(4, 202) ¼ 24.58, p 5 .001. The effects of child gender and the interaction between country and sex were nonsignificant. Follow-up univariate analyses of variances (ANOVAs) were conducted for each of the variables. Means and standard deviations of child behaviours for Chinese and Canadian children and F-ratios are presented in Table 1. The results of these analyses revealed a significant main effect of country for (a) length of time child engaged in autonomous activities, (b) child’s initiation of connectedness, and (c) child’s engagement (time duration) of connectedness. Nonsignificant differences were found for child’s initiation of autonomous activities. The results indicated that Chinese children spent less time on the autonomous activities in a novel situation. Moreover, compared with the Canadian children, Chinese children exhibited more connectedness to mother as reflected by both the frequencies of initiation and the time duration. Comparisons across cultures on maternal goal-oriented behaviours .001. The effects of child sex and the interaction between country and sex were nonsignificant. Follow-up ANOVAs based on raw scores of maternal goaloriented behaviours indicated a significant main effect of country for all the variables. Specially, Chinese mothers had significantly higher scores than Canadian mothers on both encouragement of autonomy and encouragement of connectedness. The results suggested that Chinese mothers were generally more involved than Canadian mothers in mother–child interactions. To understand the nature of maternal parenting in Chinese and Canadian mothers and to examine whether there were cross-cultural differences in the qualitative aspects of maternal parenting, further analyses were conducted, controlling for the differences in the total number of maternal interventions. In these analyses, relative scores of maternal goal-oriented behaviours were computed by dividing the frequency of a behaviour by the total number of maternal goal-oriented behaviours. A MANOVA was conducted to examine whether there were country and sex differences in the relative scores of maternal goal-oriented behaviours. A significant multivariate main effect was obtained for country, Wilks ¼ .96, F(1, 164) ¼ 7.23, p 5 .01. The effects of child gender and the interaction between country and sex were nonsignificant. Follow-up ANOVAs indicated a significant main effect of country for both maternal encouragement of autonomy and maternal encouragement of connectedness. Specifically, Canadian mothers had higher scores on encouragement of autonomy, and lower scores on encouragement of connectedness than Chinese mothers. Means and standard deviations of raw and relative scores of maternal goal-oriented behaviours and F tests are presented in the lower part of Table 1. Correlations between child behaviours and maternal behaviours A MANOVA was conducted first to examine whether there were country and sex differences in the raw scores of maternal goal-oriented behaviours. A significant multivariate main effect was obtained for country, Wilks ¼ .64, F(2, 202) ¼ 56.53, p 5 Child behaviours were standardized and then aggregated to form two major variables, child autonomy and child connectedness. The correlations between child behaviours and maternal behaviours (raw scores) are presented in Table 2. A Table 1 Means and standard deviations of child behaviours and maternal goal-oriented behaviours in China and Canada China Variable Mean SD Canada Minimum Maximum Mean SD Minimum Maximum F value Child behaviours Autonomy Initiation Length of time Connectedness Initiation Length of time 13.02 396.80 8.34 113.74 1.87 20.30 71.45 630.98 11.40 512.62 4.51 88.27 0.00 260.70 24.68 633.33 ns 66.78*** 6.47 187.64 4.64 162.99 0.00 0.00 23.78 654.24 2.99 122.02 2.31 121.27 0.00 0.00 10.98 524.71 44.40*** 11.29*** Maternal goal-oriented behaviours Raw scores Encourage. of Encourage. of Relative scores Encourage. of Encourage. of autonomy connectedness 11.43 7.68 10.28 8.35 0.00 0.00 50.00 43.98 1.90 0.94 2.97 2.05 0.00 0.00 22.76 14.49 76.41*** 59.81*** autonomy connectedness 0.62 0.38 0.30 0.31 0.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 0.76 0.24 0.33 0.33 0.00 0.00 1.00 1.00 7.23* 7.23* * p 5 .05; *** p 5 .001. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BEHAVIORAL DEVELOPMENT, 2005, 29 (6), 489–495 similar pattern of correlations was revealed for the two samples. In general, child connectedness was positively associated with maternal autonomy- and connectednessoriented behaviours, whereas child autonomy was negatively associated with maternal variables. The magnitude of the correlation coefficients did not differ between the samples. Discussion The role of parenting in children’s socioemotional and cognitive development has been one of the central issues in developmental research. It has been found that parental behaviours toward the child may have a long-term impact on parent–child relationships and the child’s adaptive and maladaptive functioning (e.g., Parke & Buriel, 1998; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). Among various aspects of parenting, psychologists have been interested in fundamental dimensions such as parental warmth/responsiveness and control (e.g., Baumrind, 1967, 1971; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Findings from empirical research has indicated that parental warmth, control, and categories based on these dimensions, such as authoritative and authoritarian styles, are associated with children’s social competence and behaviours in various areas (e.g., Booth, Rose-Krasnor, McKinnon, & Rubin, 1994; Dishion, 1990; Hart, DeWolf, Wozniak, & Burts, 1992; Russell & Russell, 1996). Given this background, it is not surprising that cross-cultural research has focused on parental warmth and control and related issues (e.g., Chen, Dong, & Zhou, 1997; Chen, Liu, & Li, 2000; Rohner, 1986). As indicated above, however, it is important to investigate aspects of parenting behaviours that are more culturally relevant in order to better understand how cultural values are involved in the socialization processes. In the present study, we attempted to explore, in Chinese and Canadian samples, two specific parenting behaviours in mother–child interactions that are directly associated with important socialization goals. Cross-cultural differences in overall maternal involvement The results first indicated that, compared with Canadian mothers, Chinese mothers had higher raw scores on both encouragement of autonomy and encouragement of connectedness, indicating greater overall involvement in their interactions with the child. This is consistent with previous findings that Chinese parents are more likely than Western parents to Table 2 Correlations between child behaviours and maternal behaviours Maternal encouragement of China Child Child Canada Child Child Autonomy Connectedness autonomy connectedness –.37** .35** –.25* .56** autonomy connectedness –.26* .41** –.15 .60** Analyses were conducted based on raw frequency scores. * p 5 .05; ** p 5 .01. 493 report concern, control, and intervention in child-rearing (Chao, 1994; Chen et al., 1998). The greater parental involvement in Chinese mothers may be related to the particular emphasis on the responsibility of parents for caring and disciplining children in Chinese culture (Ho, 1986). This responsibility has also been stressed in contemporary China since the ‘‘only child’’ policy was implemented in the early 1970s. It is generally believed that ‘‘only’’ children in China are likely to be indulged or over-indulged in the family and have pervasive negative behavioural qualities and adjustment problems including impulsiveness, aggressiveness, and selfishness (Jiao, Ji, & Jing, 1986). Thus, parents are encouraged to exert greater supervision and control from the early years in addition to provide care and guidance to the child. The cross-cultural differences in overall maternal involvement may also be a function of the differences in behavioural characteristics between Chinese and Canadian children. The results indicated that Chinese children had higher scores on connectedness than Canadian children, indicating that Chinese children were more likely to display affiliative behaviours and physical proximity to the mother. These behaviours might provide Chinese mothers with more opportunities to engage in interactions and exert interventions on the child’s behaviours. In addition, the overall high maternal involvement in Chinese mothers may be related to the laboratory setting. Although the same procedures were used for the Chinese and Canadian samples, mothers in the two samples might interpret and respond to the laboratory observation differently. Indeed, some Chinese mothers explicitly expressed their concerns about their children’s performance during the visit. Questions such as ‘‘Was my kid good (normal, well-developed)?’’ were often raised with the experimenter after the sessions were completed in China. As such, Chinese mothers may have exerted a high level of direction and involvement in mother– child interactions. Cross-cultural differences in the nature of maternal behaviours Besides overall maternal involvement in mother–child interactions, we were interested in the nature or ‘‘quality’’ of maternal behaviours and differences between Chinese and Canadian mothers on the relative scores of the behaviours. We expected that Canadian mothers would display relatively more autonomy-oriented behaviours than Chinese mothers and that Chinese mothers would display more connected-oriented behaviours than Canadian mothers in their interactions with the child. This hypothesis was supported by the results. After controlling for the overall level of maternal involvement, Chinese mothers had higher scores on the encouragement of connectedness than Canadian mothers, whereas Canadian mothers had higher scores on encouragement of autonomy than Chinese mothers. Therefore, despite the cross-cultural differences on the overall maternal involvement, when Canadian and Chinese mothers exerted interventions, Canadian mothers’ behaviours were relatively more directed to the encouragement of child autonomy, whereas Chinese mothers’ behaviours were more oriented toward the encouragement of connectedness. It has been argued that relative to Western cultures, Chinese culture has traditionally placed great value on interpersonal cooperation and harmonious relationships (Ho, 1986; Triandis, 1990; Yang, 1986). In contrast, individual self-direction 494 LIU ET AL. / MATERNAL PARENTING BEHAVIOURS and personal autonomy are considered more important in North America than in Chinese, and perhaps some other, group-oriented societies (Larson, 1999; Triandis, 1990). The cultural values may serve as a basis for the formation of parental socialization beliefs and goals (Ho, 1986; Larson, 1999). The results of the present study indicated that cultural emphasis on autonomy or connectedness was reflected in maternal parenting behaviours in mother–child interactions. Given the proximal influence of parenting behaviours on child development (e.g., Belsky, 1984; Booth et al., 1994; Hart et al., 1992; Russell & Russell, 1996), it may be reasonable to argue that the culturally directed parenting behaviours are likely to lead to different developmental outcomes in Chinese and Canadian children. The results concerning the crosscultural differences may also help us understand the findings that Chinese parents are less authoritative than North American parents in child-rearing (e.g., Chao, 1994; Dornbusch et al., 1987), because encouragement of autonomy is an important component of inductive authoritative parenting style (Baumrind, 1971; Steinberg, Elman, & Mounts, 1989). Therefore, the encouragement of autonomy in Chinese mothers and the display of autonomous behaviours in Chinese children may be a result of recent macro-level social and cultural changes. Cross-cultural similarities were also reflected in the correlations between maternal goal-directed behaviours and child behaviours. In both samples, maternal encouragement of connectedness and autonomy was positively correlated with child connectedness and negatively correlated with child autonomy. The results suggested that mothers were likely to be involved when children displayed connectedness-oriented behaviour, but not when children were engaged in autonomous activities. The high contingency between maternal involvement and child connectedness-oriented behaviours is not surprising given that they represent two integral components of mother– child interactions. The results may also reflect a limitation of the observational procedure and the behavioural coding system. Other research methods such as interviews and selfreports may be more useful and effective in providing independent data about maternal and child behaviours. Cross-cultural similarities Limitations and future directions Although there were differences between Chinese and Canadian mothers on goal-oriented behaviours, cross-cultural similarities were observed in the present study. In both samples, mothers had higher scores on encouragement of autonomy than on encouragement of connectedness. Chinese and Canadian mothers both encouraged their children to engage in more autonomous behaviours than affiliative and cooperative behaviours. The similar within-culture patterns concerning maternal encouragement of autonomy vs. connectedness might indicate some common features of the socialization and developmental processes. During the toddler years, a major developmental task is to learn self-sufficiency in various activities including toileting, feeding, walking, exploring, and talking (e.g., Erikson, 1950; Schaffer & Crook, 1980). The rapid growth in children’s locomotor and cognitive abilities constitutes the necessary condition for autonomous pursuits. Our results suggest that parents in different cultures may understand the need of toddlers to develop autonomous behaviours and, thus, deliberately encourage them to explore the environment and learn independence and self-governance. The cross-cultural similarities indicate that, across cultural contexts, the socialization processes may be determined, to a large extent, by the basic requirements in human development. The higher encouragement of autonomy in Chinese mothers may also be due to the fact that whereas Chinese parents value interdependence and connectedness, especially within the family, individual independence is not necessarily discouraged (Chen et al., 1998; Lin & Fu, 1990). Chinese mothers may realize that in order to function adequately in a larger society and to adjust to the changing demands of contemporary society, children need to learn independent and assertive skills. This may particularly be the case in urban China, as the large-scale economic reforms in the country toward the capitalistic system and the introduction of Western ideologies may lead to changes in parental child-rearing attitudes and behaviours. In the new, competitive environment, behavioural characteristics that facilitate the achievement of personal goals such as social initiative and independence may be increasingly valued and encouraged. There were several limitations and weaknesses in the study. First, based on the literature (e.g., Chen, 2000; Ho, 1986; Maccoby & Martin, 1983), we believe that encouragement of autonomy and encouragement of connectedness are two major socialization goals adopted by parents in most societies, although the degree to which they are emphasized may vary across cultures. There may be other important socialization goals such as encouragement of self-control and responsibility. Future research should be expanded to examine parenting behaviours related to other socialization goals. Second, data in the present study were collected from observing mother–child interactions and peer interactions in a laboratory situation. Although the situation was designed to induce maternal and child behaviours typically seen in the naturalistic setting, it is still uncertain how accurately the behaviours observed reflect maternal and child behaviours in ‘‘real-life’’ situations. To achieve better ecological validity, it is important to observe parent–child interactions in naturalistic settings such as home and daycare centres. Despite the limitations, the study provided valuable information about maternal goal-oriented behaviours from a cross-cultural perspective. References Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachment as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75, 43–88. Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4 (1, Pt. 2). Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96. Bond, M. H. (1991). Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. Booth, C. L., Rose-Krasnor, L., McKinnon, J., & Rubin, K. H. (1994). Predicting social adjustment in middle childhood: The role of preschool attachment security and maternal style. Social Development, 3, 189–204. Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development, 65, 1111–1119. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BEHAVIORAL DEVELOPMENT, 2005, 29 (6), 489–495 Chen, X. (2000). Growing up in a collectivistic culture: Socialization and socioemotional development in Chinese children. In A. L. Comunian & U. P. Gielen (Eds.), Human development in cross-cultural perspective. Padua, Italy: Cedam. Chen, X., Dong, Q., & Zhou, H. (1997). Authoritative and authoritarian parenting practices and social and school performance in Chinese children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21, 855–873. Chen, X., Hastings, P. D., Rubin, K. H., Chen, H., Cen, G., & Stewart, S. L. (1998). Child-rearing attitudes and behavioral inhibition in Chinese and Canadian toddlers: A cross-cultural study. Developmental Psychology, 34, 677– 686. Chen, X., Liu, M., & Li, D. (2000). Parental warmth, control and indulgence and their relations to adjustment in Chinese children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 401–419. Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R M. (1985). The General Causality Orientations Scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19, 109– 134. Dishion, T. J. (1990). The family ecology of boys’ peer relations in middle childhood. Child Development, 61, 874–892. Dornbusch, S., Ritter, P., Leiderman, R., Roberts, D., & Fraleigh, M. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development, 58, 1244–1257. Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. Oxford: Norton. Gough, H., & Heilbrun, A. L. (1983). The Revised Adjective Checklist manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Greenfield, P. M. (1994). Independence and interdependence as developmental scripts: Implications for theory, research, and practice. In P. M. Greenfield & R. R. Cocking (Eds.), Cross-cultural roots of minority child development (pp. 1– 40). Hillsdale. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Greenfield, P. M., & Suzuki, L. K. (1998). Culture and human development: Implications for parenting, education, pediatrics, and mental health. In W. Damon (Editor-in-Chief), I. E. Sigel & K. A. Renninger (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 4, Child psychology in practice (pp.1059–1109). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Hart, C. H., DeWolf, D. M., Wozniak, P., & Burts, D. C. (1992). Maternal and paternal disciplinary styles: Relations with preschoolers’ playground behavioral orientations and peer status. Child Development, 63, 879–892. Ho, D. Y. F. (1986). Chinese pattern of socialization: A critical review. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The psychology of the Chinese people (pp. 1–37). New York: Oxford University Press. Ho, D. Y. F. (1987). Fatherhood in Chinese culture. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The father’s role: Cross-cultural perspective (pp. 227–245). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Hodgins, H. S., Koestner, R., & Duncan, N. (1996). On the compatibility of autonomy and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 227– 237. Jackson, D. N. (1984). Manual of the Personality Research Form. Port Huron, MI: Research Psychologists Press. Jiao, S., Ji, G., & Jing, Q. (1986). Comparative study of behavioral qualities of only children and sibling children. Child Development, 57, 357–361. Kochanska, G., Kuczynski, L., & Radke-Yarrow, M. (1989). Correspondence between mothers’ self-reported and observed child-rearing practices. Child Development, 60, 56–63. Kucyzynski, L., & Kochanska, G. (1990). Development of children’s noncompliance strategies from toddlerhood to age 5. Developmental Psychology, 26, 398–408. 495 Larson, R. W. (1999). The uses of loneliness in adolescence. In K. J. Rotenberg & S. Hymel (Eds.), Loneliness in childhood and adolescence (pp. 244–262). New York: Cambridge University Press. LeVine, R. A., Miller, P. M., & West, M. M. (1988). Parental behavior in diverse societies. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Lin, C. C., & Fu, V. R. (1990). A comparison of child-rearing practices among Chinese, immigrant Chinese, and Caucasian-American parents. Child Development, 61, 429–433. Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, C. N. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality and social development (pp. 1– 102). New York: John Wiley. Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 20, 568–579. Miller, J. G. (2002). Bring culture to basic psychological theory—Beyond individualism and collectivism: Comment on Oyserman et al. (2002). Psychological Bulletin, 128, 97–109. Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72. Parke, R. D., & Buriel, R. (1998). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 463–552). New York: Wiley. Rohner, R. P. (1986). The warmth dimension: Foundation of parental acceptancerejection theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Rubin, K. H., & Burgess, K. B. (2002). Parents of aggressive and withdrawn children. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1: Children and parenting (2nd ed., pp. 383–418). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Russell, A., & Russell, G. (1996). Positive parenting and boys’ and girls’ misbehavior during a home observation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 19, 291–307. Schaffer, H. R., & Crook, C. K. (1980). Child compliance and maternal control techniques. Developmental Psychology, 16, 54–61. Sigel, I. E. (Ed.). (1985). Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Steinberg, L., Dornbusch, S., & Brown, B. B. (1992). Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement: An ecological perspective. American Psychologists, 47, 723–729. Steinberg, L., Elman, J. D., & Mounts, S. (1989). Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success among adolescents. Child Development, 60, 1424–1436 Triandis, H. C. (1989). The self and behavior in different cultural contexts. Psychological Review, 96, 506–520. Triandis, H. C. (1990). Cross-cultural studies of individualism and collectivism. In J. J. Berman (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1989: Cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 41–133). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. Whiting, B. B., & Edwards, C. P. (1988). Children of different world: The formation of social behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press Wu, P., Robinson, C. C., Yang, C., Hart, C. H., Olsen, S. F., Porter, C. L., Jin, S., Wo, J., & Wu, X. (2002). Similarities and differences in mothers’ parenting of preschoolers in China and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 481–491. Yang, K. S. (1986). Chinese personality and its change. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The psychology of the Chinese people (pp. 141–154). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.