Seminar Hand-out Liberalism vs Realism

advertisement

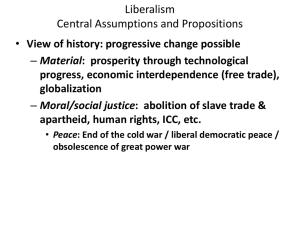

MA Seminar Handout - 10/10/11 - Martin Rowse MA Seminar - Group 2 - 10th October, 2011 Martin Rowse Q2. Does liberalism provide a viable alternative to realism as a theory of international relations? Theories are established or evolved as a way of explaining a complex and often opaque subject in a clear and useful way - when they resonate they become tools to explain and explore subjects. Within this short hand-out and presentation I aim to set a juxtaposition between the theories of Realism and Liberalism to examine which one provides the most useful theory for international relations. I will argue that both Realism and Liberalism are useful theories when considering international relations, and in fact having the two opposing views adds to the discussion. Bayliss and Smith describe these two theories as Realism being the “‘natural’ party of government and Liberalism (as) the leader of the opposition.”1 I will argue that this analogy rather underplays the importance, relevance and usefulness of Liberalism in our Globalised world. When considering the theories of Liberalism and Realism it should be pointed out that both rely on the sanctity of the Nation State, this paper will not explore this element but it is an important consideration when evaluating both theories. Realism: the natural home for international relations It is easy to argue that Realism has been the predominant theory in the previous decades, this is most prevalent in the language and naming principles of the epochs throughout time which are always pre- or post- a set conflict. This is at first glance not significant, but if you consider the naming principles in other areas of academia they represent a type of thought or in art the style of painting. This is an important distinction, as the naming principle often sets the language that will be used to describe events, and when each era is described in the context of a conflict then it is natural to consider that conflict as the key differentiator. It is also true to say that realism has a natural home in international relations, which has always traditionally focused on the conflicts and tensions between nations. This could be for a number of reasons; but is most likely due to the large-scale conflicts that have shaped and re-shaped the world in the last century. The most recent of which was the Cold War which proved Realism on the global scale as the bi-polar world between the US and USSR seemingly edged closer to conflict through continuous competition. There are three main types of Realism which have been developed as the theory is continually challenged by actual events. Classic Realism focuses on the innate desire for humans to dominate one-another2 and extrapolates this view to states. Neorealism Tim Dunne ‘Liberalism pp.186 in J Balylis and S Smith, The Globalisation of World Politics (Oxford: OUP, 2005) 2 S Walt, ‘International Relations: One World, Many Theories’, Foreign Policy No.110, pp. 31 1 1 MA Seminar Handout - 10/10/11 - Martin Rowse suggests that all states are seeking to survive within an international system, but as that system is anarchic in nature each state must survive on its own. Burchill describes this as states being “thwarted by the absence of an overarching authority which regulates their behaviour towards each other.”1 The latest addition to Realism is the offence-defence school of thought, which suggests that “war was more likely when states could conquer each other easily. When defence was easier than offence, however, security was more plentiful, incentives to expand declined and cooperation could blossom.”2 This line of thought may seen fairly logical, that a state will only engage another state where it believes it has the ability to win. However, it could be used to explain why the number of state-on-state actions has decreased3 without discounting the whole Realist way of thinking. Realism is certainly an easier theory to define, and provides a simple measure for the casual observer of international relations. However, this focus on conflict may mean that we fail to notice other changes in the international relations environment, especially in terms of how different nations solve problems and disagreements, with the focus shifting towards cooperation. It could also be argued that each new state-on-state conflict strengthens the case for realism and in turn weakens the case for liberalism. This is a compelling argument, especially considering that liberalism has no similar way to demonstrate it’s ‘success’ as a theory as the number of conflicts avoided through diplomacy and international organisations is not recorded or clear. I would therefore suggest that this argument is disingenuous, since one theory has a clear demonstration of when it is correct (i.e. stateon-state conflict) where liberalism has no such clear measure. This is also discussed later where Liberalism is often popular following a conflict to develop a solution. Liberalism: when international relations is more than conflict One could explain Liberalism as having a focus on peaceful-coexistence, where it looks to explain how nations can exist side-by-side within a stable and ordered international system - it looks to ‘self-restraint, moderation, compromise and peace’2. This is not necessarily the opposite of Realist thinking of the world in constant tension and conflict, but see institutions and mechanisms other than conflict. Liberalism espouses an international system made up of institutions which combine multiple Nation States, where Realism only sees anarchy it the international system and conflict inevitable between states. 1 Scott Burchill, ‘Liberalism’ pp.57 in S Burchill et al, Theories of International Relations (Basingstoke: Palgrave 2005) 2 S Walt, ‘International Relations: One World, Many Theories’, Foreign Policy No.110, pp. 31 3 H Buhaug, S Gates et al. Global trends in armed conflict, International Peace Research Institute, Oslo. www.regjeringen.no. Accessed 04/10/11. 4 Hoffmann extract within J Balylis and S Smith, The Globalisation of World Politics (Oxford: OUP, 2005) 2 MA Seminar Handout - 10/10/11 - Martin Rowse The Liberalist way of thinking is made of four main pillars: Citizenship All Citizens are equal and possess certain basic rights to eduction, free press and religious tolerance Legitimacy The legislative authority only possesses the authority invested in it by the people Property The right to own property is key to individual liberty Trade The most effective system of exchange is through the markets1 Liberalists see a direct extension between domestic and international, it is seen as an “inside-out” theory from this respect as it looks at how best to translate domestic policy in to the international relationships2. This is an important distinction when considering whether Liberalism is a viable theory to understand international relations, especially since it also considers how best to ensure the legitimacy of policy through international organisations and mechanisms. As with Realism there are a number of schools of thought; but each one reflects the main principle that “the crucial variables in explaining the behaviour of states at the international level relate to the domestic level.”3 Essentially, the behaviour of the domestic is amplified to the international level, but not significantly changed. The first school argues that Economic Interdependence - the inter-twining of states economies - will discourage conflict as it would result in damage to both. Secondly, a view that the spread of democracy itself would lead to peaceful coexistence. This does not mean that democracies are any more peaceful, but “democracies rarely go to war against each other.”4 Finally, the theory of International Institutions which focuses on the pacifying nature of the institutions that have been set up in the preceding decades.3 This largely applies to the power-dividing institutions which require a coalition or alliance to wage war, which makes the decision more difficult as you are relying on multiple actors wishing to embark on the same course of action.5 However, as mentioned above you cannot deny the existence of state-on-state conflict in the 20th Century, which it could be argued removes the importance of Liberalism completely. Liberalism has indeed been intermittently popularity throughout the last century, stemming largely from the conflicts which have marked out the 20th Century, such as the two World Wars and then the Cold War. Rather than take away from the Liberalist theory, these conflicts have in fact added substantially to the argument. Most notably the reliance on Liberalist thinking at the end of major conflicts - this includes the League of Nations foundation following First World War and the establishment of United Nations at the end of the Second World War6. Following S Walt, ‘International Relations: One World, Many Theories’, Foreign Policy No.110, pp. 32 Burchill, ‘Liberalism’ pp.81 in S Burchill et al, Theories of International Relations (Basingstoke: Palgrave 2005) 3, 4, 5 D Pante and T Risne, ‘Liberalism’, pp 91, 96 in T Dunne and S Smith, International Relations Theory (Oxford: OUP, 2007) 1 2 Scott 6 P Calvocoressi, pp. 151 in World Politics 1945 - 2000 (Longman, 2001) 3 MA Seminar Handout - 10/10/11 - Martin Rowse the Cold War in the 1990s state leaders began to proclaim a “New World Order” of international institutions and liberal ideas.1 It should also be remarked upon that a number of non-conflict subjects are now being discussed amongst nations; including Human Rights and ethical considerations2. If this trend becomes permanent it will once again show the strength of coexistence over the Realist view of conflict as a natural course of events. Realism versus Liberalism: is there a knock-out blow? Setting the two theories against each other shows two polar-opposite ways of thinking about international relations. This opposition forces a choice, and therefore fosters discussion. Realism Liberalism State-on-state actions Domestic internal to state International scene of anarchy International Organisations Reflective and history-focused Forward-looking State-focused Citizen-focused Competition Trade Conflict Peaceful co-existence One could argue that liberalism represents a more progressive and optimistic future, in fact it could be said that globalisation has been pursuing liberalist goals throughout the last decades. Fukuyama’s view was that human progress could be measured in the reduction and eventual elimination of global conflicts through the evolution of legitimate principles in domestic policy.3 Without Liberalist thinking, we w4ould not have the United Nations, International Monetary Fund or any of the gradually increasing number of international organisations if it were not for the first attempt at creating an international authority in the League of Nations. All these efforts are attempting to prove true Kant’s statement that peace can be perpetual.4 D Pante and T Risne, ‘Liberalism’, pp 186 in T Dunne and S Smith, International Relations Theory (Oxford: OUP, 2007) 2, 3, 4 Scott Burchill, ‘Liberalism’ pp.81, 56, 58 in S Burchill et al, Theories of International Relations (Basingstoke: Palgrave 2005) 4 1 MA Seminar Handout - 10/10/11 - Martin Rowse Figure 1: Realism and Liberalism along a Paradigm of Thought This view of an ever increasing number of international institutions and mechanisms that we also see a fall in the number of state-on-state conflicts which would suggest either conflict has been temporarily suspended or perhaps new non-aggressive methods of conflict - such as trade negotiations - have replaced the previous weapons. With this in mind I would suggest that Realism and Liberalism can be placed on a paradigm (Figure 1, above) which provides a useful frame for the theories to be considered within. Conclusion I believe that Liberalism can indeed be a viable alternative to Realism when dealing with International Relations; as it helps us understand and explain the non-aggressive methods and actions being taken by national states on the international stage. The age of state-onstate conflict may not be behind us, but the importance of conflict between democracies has certainly been reduced. It is therefore more important that we understand the non-conflict and non-aggressive actions of our states, to ensure that our international institutions are fit-for-purpose and we as states understand the implications of our actions. I would suggest that rather than realism and liberalism being separate theories, they are in fact better understood when placed together at opposing ends of a paradigm. I would go so far as to say that the two theories can only truly exist in a useful form when they are placed together, with the pendulum swinging between each theory as time progresses, leadership changes and methods are refined or dissolved. One could argue that realism and liberalism represent a “balance of thought” for international relations. Martin Rowse (123) 2,051 Words 5