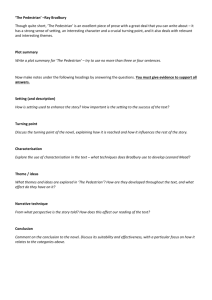

Pedestrian Network Analysis

advertisement