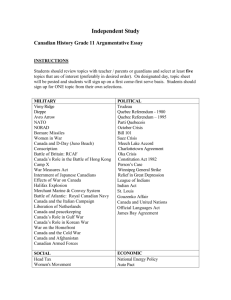

"Quebec and Canada at the Crossroads: A Nation within a Nation"1

advertisement