To Engage the Viewer: The Relationship between

advertisement

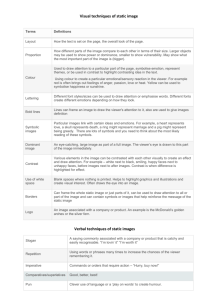

To Engage the Viewer: The Relationship between Narrative and the Viewer in Hellenistic Art Jennifer Kozerawski T he act oflooking at a work of art entails much more than simply our sense of sight, rather it involves a complex interplay between what we see and how we perceive it. The process by which we "see" a work of art not only establishes a point of contact between the viewer and the work but also produces an immediate response, as it were, a dialogue within the viewer's mind: 1 judgments are made, questions are asked and interest is decided. As a result, the viewer no longer simply "sees" a work of art but comes to understand it, as a mode of communication is established and a relationship to the work of art takes shape. As simple as the act of looking may seem, the effects of this process of "seeing" on the viewer and on the work of art have far reaching consequences. Perhaps nowhere else in the history of ancient art was the relationship between the viewer and the work of art so explored and exploited as in the Hellenistic period. 2 Celebrated for its artistic developments in the spheres of naturalism, illusionism, spatial composition and movement, it is no surprise that the Hellenistic period inspired both its Roman successors and modern scholars and connoisseurs alike. But what exactly is it about the characteristics of Hellenistic art 1. Richard Brilliant, Visual Nan·atives: Storytelling in Etruscan and Roman Art (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1984), 16. 2. The Hellenistic period is generally relegated to the years between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C. and the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. 33 To Engage the Viewer Jennifer Kozerawski 34 that appeal to both ancient and modern viewers? \Xlhat inspired Hellenistic artists desires to the viewer. As a result, he is attempting to initiate a dialogue with the to infuse their work with a sense of animation? For what purpose, and for whom? outside world, but most importantly, a narrative is being conveyed and established The strategies the artist used to transcend the limitations of his medium, be it sculpture or painting, in order to produce a realistic and lifelike effect is with the viewer. It is, however, the Boy and Goose that exemplifies how an intimate certainly part of its appeal. By endowing works of art with those qualities naturally relationship between viewer and art takes shape. This work actively engages the inherent in the viewer's physical, spatial and visual experiences, Hellenistic artists viewer in a mode of communication, not only by emulating the behavior and increasingly engaged their audience by creating an ambiguity between the "real" and appearance of the living, but also by involving the viewer directly in an unfolding the "unreal". The interest of Hellenistic artists in the development of more story. The intimate and authentic relationship this creates between the viewer and naturalistic modes of representation was coupled with the heightened awareness of the work transforms the act of "seeing" a work of art into "experiencing" a work the spectator, and the viewer, as spectator and recipient of information, provides of art. It is thus, not surprisingly, in an age characterized by a keen interest in the the key to understanding the motivation and creation of many Hellenistic works of individual, that many significant artistic innovations developed in the Hellenistic art. For example, the Terme Boxer (Fig.1; 1" Century BC) is infused with a sense period were directly rooted in modes of narrative that appealed to the viewer's of life not simply because of the accurate representation of his wounds and natural experience of reality. Not only do many examples of Hellenistic art employ physiognomy but also by the awareness he exhibits of his surroundings. The sharp a realistic depiction of the figural form as an entity existing in three-dimensional turn of the Terme Boxer's head suggests that some external stimuli has caught his space (a characteristic of the Lysippian tradition),3 they also seek to implicate the attention: he acts as an animate being. He is aware of his environment and viewer through a temporal and physical experience. As a result, narrative art interacts with the world in the same way we do. It is this which captures our extends between the viewer and a work of art. attention and instills the figure with life. This same sense acknowledgement of the outside world, and the sense of realism it conveys, can also be seen in the Boy and Goose (Fig.2; 2nd Century BC). Here the boy actively responds to something "out there," beyond himself. Sitting on the floor, the little boy looks up and reaches out with his right arm to the viewer standing above him. His body is open and excited rather than closed. His gesture reveals a sense of urgency as he desperately tries to communicate his needs and 3. Although the years iu which Lysippos worked actively as an artist are variously debated, (anywhere from a period beginniug as early as 370 B.C. and finishiug as late as 305 B.C.) it is certain that he held a prominent position as court sculptor for Alexander the Great within the years 336-323 B.C. The work of Lysippos and his school had a profound influence on the form and composition of Hellenistic sculpture. His famous Apoxyomenos (Man Scraping Himself) introduced a new canon of proportions in the representation of the human form based on optical perception. By reducing the size of the head and elongating the length of the torso, Lysippos was able to impress a greater sense of height in the figure. In addition, by the projection of the arm into space, Lysippos' Apoxyomenos broke open the conventional closed envelope composition of Greek sculpture and urged the viewer to contemplate the figure from various points of view. 35 To Engage the Viewer As such, a work of art no longer simply functions as an end in itself, as Jennifer Kozerawski 36 continuous narrative is clearly represented on the Telephos frieze surrounding the "meaning in a work of narrative art is a function of the relationship between the inner colonnade of the interior court located on the Great Altar of Zeus at two worlds, the fictional world created by the author and the real world." 4. Its Pergamon. Dated around 180-60 B.C. and erected by Eumenes II, the frieze point of reference is the viewer, who exists beyond the work yet within the reality depicts the story of the foundation of the city of Pergamon by its self-proclaimed to which the work is referring. Consequently, the meaning and purpose of a work ancestor Telephos, son of Herakles and Auge. \X'hat is particularly distinctive are dependent on the viewer. This relationship between the viewer and a work of about the pictorial mode of continuous narrative is the repetition of one or more art is not only crucial to understanding the work's overall meaning, it is also a key figures (in this case Telephos) across the pictorial expanse, performing actions that consideration during the work's initial conception and creation.s are clearly intended to take place at different moments in time. The story is In contrast to statues, however, the challenge to create a narrative artistic represented as unfolding in a continuous and uninterrupted sequence of space and language based on human experience is perhaps most telling in the spheres of time with a clear beginning and end. This is facilitated by a continuous, albeit painting and relief due to the inherent problems of translating the three- shifting background,10 in which compositional elements such as trees and columns dimensional world into a language of two-dimensional visual images that would be serve to delineate changes in locale, such as the cities ofTegea and Mysia in the both comprehensible and believable.6 George Hanfmann notes that "all human Telephos story. Atmosphere, depth and perspective are realistically rendered by actions unfold in time and are carried out in space." 7 The solution was both the diminution of certain figures and also, as in the case of Auge and her retinue, by convincing and innovative, in contrast to the principles of classical narrative art, placing the figures higher up on the picture plane to imply the recession of space. II where figures are generally isolated from one another, events occur in a timeless The frieze is thus constructed as a two-tiered composition; figures that are meant moment, and the background provides little indication of space or depth. 8 The to appear closer to the viewer are placed in the foreground while those figures development of continuous narrative in Hellenistic art aimed to unify all of these further away are placed higher up and are rendered on a smaller scale.12 This is at pictorial elements into a logical and coherent whole. 9 The employment of once a significant departure from the classical tradition, where ftgures often occupy the entire height of a frieze, and a conscious acknowledgement on the part of the 4. Brilliant, 16. 5. Andrew Stewart, "Narration and Allusion in Hellenistic Baroque," in Nan·ative and Event in Ancient Art, ed. Peter J. Holliday (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 132. 6. Peter H. von Blanckenhagen, "Narration in Hellenistic and Roman Art," American Journal ofArchaeology 61 (1957): 83. 7. George M.A. Hanfmann, "Narration in Greek Art," American Journal ofArchaeology 61 (1957), 71. 8. R.R.R. Smith, Hellenistic Sculpture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991), 164-165. 9. von Blanckenhagen, 79-82. artist as to the principles of optical perception and experience. 10. Pollitt, 200. 11. Andrew Stewart, "A Hero's Quest: Narrative and the Telephos Frieze," in Pet:gamon: The Telephos Frieze from the Great Altar, Vol. 1, edited by Renee Dreyfus and Ellen Schraudolph (San Francisco, California: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), 40-42. 12. Smith, 165. 37 To Engage the Viewer The Telephos frieze was originally situated at eye level, and was 80 to 90 Jennifer Kozerawski 38 with the Telephos frieze, scenes are depicted one after the other, and the figures are meters in length. Along with the realistic portrayal of perspective, proportion and repeated in a forward moving sequence. However, there is little in terms of detail, scale, 13 this format urged the spectator to view the story consecutively as he or she differentiation among figures, or delineation oflocale as on the Telephos frieze. It walked along adjacent to it. This involved the viewer both physically and is, rather, the bowl inscriptions, located above the figures' heads, which identify the temporally, as one had to walk along the frieze in order to understand its whole stories being depicted. meaning. By physically following the frieze, the viewer can mentally engage with The Telephos frieze influenced classical painting in its use of continuous the events of the Telephos narrative. 14 Peter von Blanckenhagen has observed; the narrative and its consequent appeal to the viewer. 18 The Odyssey Landscapes (Fig. composition of the Telephos frieze, much like events in reality, cannot be viewed in 3) exemplify these characteristics. The Odyssey paintings are often referred to as a a single moment but must unfold over time. 15 The use of an uninterrupted and frieze and regarded as a whole, although the scenes depict several of Odysseus's forward moving story provides cohesiveness, despite the changes in time and place. adventures from Books 10 and 11 of Homer's Odyssey, divided by illusionistically However, this is only achieved by the direct involvement of the viewer, who painted pilasters, suggesting the idea of an exterior view. It is thought that in the actualizes the frieze through his or her viewing of it. 16 The frieze itself does not Hellenistic original, on which these paintings were based, the scenes were narrate the story but provides the necessary visual cues for narration. It is the conjoined as one continuous landscape painting. Unlike the Telephos frieze, in the viewer who narrates the story and "must change the imagery into some form of Odyssey paintings the landscape is the main element, and almost envelops the small internalized verbal expression." 17 This relationship between the viewer and the figures of Odysseus and his men, who are minute in relation to the overall pictorial work of art is fundamental in all works of narrative art. space. The use of soft colours and atmospheric perspective adds a lively quality Possible antecedents for the continuous narrative found on the Telephos now missing in the Telephos frieze, which, it should be mentioned, was also once frieze remain uncertain and are a topic of much debate. One fertile source may painted. While the Telephos frieze aims to portray a convincing sense of time and have been a group of Megarian bowls, known more commonly as the 'Homeric place with its limited use of landscape elements and focus on the protagonists, the Bowls' (ca. 175-125 B.C.). These drew their subject matter from Greek epic poetry Odyssey landscapes employ nature as their primary vehicle for presenting pictorial such as the Il!iad and the Odyssey and dramas such as the tragedies of Euripides. As narrative. The Hellenistic artists' awareness of the limitations of their media was not 13. 14. 15. 16. von Blanckenhagen, 82. Holliday, 10. von Blanckenhagen, 79. Pollitt, 200. 17. Holliday, 4. lost in their attempts to bring a story to life. While the Telephos frieze occupied 39 To Engage the Viewer Jennifer Kozerawski 40 the inner court of the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, closed off from the world, before our vety eyes, making it present by representing the situation as if in a state the Gigantomachy frieze (ca. 180 B.C.) that adorned the outer walls of the altar of actuality," 21 and thus directly implicating the viewer. Nike's head, which is now offers a strikingly different solution to the questions of realism. The frieze is lost, would have originally turned to the left, and, like the Terme Boxer, would occupied by the Gods and Giants who are carved in such high relief that they seem appear engaged by something. Andrew Stewart proposes that she would have been to protrude and loom over the viewer. 19 The technique seems to defy the restricting facing the viewers. 22 As a result, the focus of the composition implies its two-dimensional medium. Even more striking is the way in which the artists have spectators, who are transformed into active participants. made the figures on the east side of the frieze share the space of the viewer; the Directly including the viewer in the composition of a three-dimensional sculpted figures emerge onto the real stairs of the altar (Fig. 4). This sculptural narrative is also pivotal to the Lesser Attalid Dedication on the Akropolis acknowledgment of the outer physical world results in an unusual and unique state in Athens (ca. 200 B.C.). Representing several historical and mythological battles, of ambiguity. But paradoxically, as opposed to representing a continuous narrative, the dedication depicts dead and dying Giants, Amazons, Gauls and Persians. The the Gigantomachy frieze presents a single event in a dramatic, dynamic and extant figures were originally accompanied by nearly a hundred other sculptures timeless moment. 20 The viewer is ultimately unable to comprehend it as such with and were placed on or near the south wall of the Akropolis. Although the the frieze running along the three sides of the altar; rather, the work can only be composition of the group is uncertain, it is clear that the figures were placed on understood sequentially, by walking along beside it, rather than in a single glance. plinths directly on the ground rather than on bases. The most controversial aspect As a result, despite the realistic depiction of movement, action and theatricality of this sculptural group was whether or not victors were depicted. With the figures facilitated by the deep carving and animation of the figures, the extended scene placed directly on the ground, the viewer is thus encouraged to walk around and seems frozen in a suspended moment of indefinite time. amongst them. This not only allowed for the physical three-dimensional The technique of representing one eternal moment is also illustrated by interaction between the work of art and the viewer, to a greater extent than in the the Nike ofSamothrace (4'h Century BC). As a sculpture in the round, Nike, the works discussed thus far, but most importantly it enabled the viewer to both personification of Victory, alights upon the prow of a victorious ship, the wind identify with the defeated enemy and with Attalos himself. 23 As a result, a close dramatically blowing in the drapery behind her. The Rhodian artists set "the scene relationship between the viewer and the sculptural group of the Lesser Attalos Dedication was achieved. Physically, by directly placing the figures in the immediate 18. Stewart, "A Hero's Quest," 42. 19. "The massive Zeus appears to burst out of the east frieze and the Giants threaten to seize the viewer." Brilliant, Arts, 347. 20. Smith, 164. 21. Stewart,143. 22. Stewart,143. 41 To Engage the Viewer space of the viewer; temporally, by situating the work within an eternal moment as Jennifer Kozerawski 42 What is common in all of the modes of narrative composition discussed with the Nike of Samothrace; and finally psychologically, by appealing to the here is the correlation between the viewer and the work of art. The realism of a empathy of the viewer. Unlike the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, where the narrative created by "calling on the senses other than sight" 2 5 calls upon the narrative is condensed into a single moment, the Dedication, with its many figures viewer's imagination or phantasia26 in the telling of a story. The emphasis placed in varying stages of dying, encourages the viewer to continue the narrative in his or upon this intimate correlation between the viewer and a work of narrative art her mind. reveals the deliberate and underlying motivations of the Hellenistic artists. The idea of extending a moment in time and employing the imagination Through means of a realistic visual language, the artists were able to elicit a of the viewer to complete or extend a narrative is perhaps most forcefully explored particular emotional response and/ or impress a point of view by invoking familiar in the sculptural group of Marsyas and the Scythian slave. The figures of Marsyas conditions of perception in their work. This objective, being the intended meaning and the Scythian slave are usually represented as separate figures, although they are or message within a narrative, is fulfilled, as we have seen, by the presence of the meant to tell the story of Marsyas and his musical competition with Apollo (ca. viewer whose physica~ emotional, and psychological attention is specifically 200-150 B.C.). It is the figures' interrelation as a three-dimensional sculptural directed by the narrative composition. 27 The goal of this visual orchestration is to group that activates their narrative and their psychological meaning. This effect is lay stress upon those aspects of the narrative that serve to highlight its purpose. heightened by the fact that their composition does not direcdy represent a For example, in the sculptural group of Marsyas and the Scythian slave, it is not definitive event but an impending one, which gives the group a particular visual explicidy the recreation or manifestation of the well-known story that is of interest power. Rather than showing the musical competition itself or the subsequent to the artist, rather it is the pathos exhibited by Marsyas as consequence of having punishment, the artist has chosen to depict an intermediary moment. While the challenged a god. In both the Telephos frieze and the Lesser Attalid Dedication, Scythian looks up at Marsyas, Marsyas himself, who is hung from a tree, in turn the message was a highly political one; the frieze promotes a rule based on divine looks down at him. It has often been interpreted that the Scythian is watching origin, and the Dedication depicts the efforts expended to overcome a strong and Marsyas while he is sharpening his knife but, as Anne Weis has convincingly argued noble enemy. 28 To the ancient and modem viewer, who is invited to engage and from the posture of his body, the Scythian is in fact looking up at Marsyas for the participate in the telling of these narratives, his or her role is one of both activator first time as he rises to complete his abominable task. 24 23. Pollitt, 96. 24. Anne Weis, The Hanging Mar.ryas and its Copies: Roman Innovations in a Hellenistic Sculptural Tradition (Rome: Giorgio Bretschneider Editore, 1992), 99. 25. Weis, 99. 26. Weis, 99. 27. Stewart, 151: 28. Pollitt, 96. 43 To Engage the Viewer Jennifer Kozerawski 44 and bearer of meaning. In the effort to close the gap between viewer and art, Hellenistic artists were able to reflect the viewer's experience of the world while shaping a part of it as well. Fig 1: Bron'(! Boxer, 2nd or early 1st century B.C.. Rome, Museo National delle Terme. Fig 2: Bl!)' and Goose, 2nd century B.C.. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. 45 To Engage the Viewer Fig. 3: Odyssey Landscape, c. 50 B.C.. Rome, Musei Vaticani. Fig. 4: Gigantomachy, c. 180 B.C.. Berlin, Pergamon Museum.