Answers To Critical Legal Cases For Chapter 51 51.1 Audit Opinion

advertisement

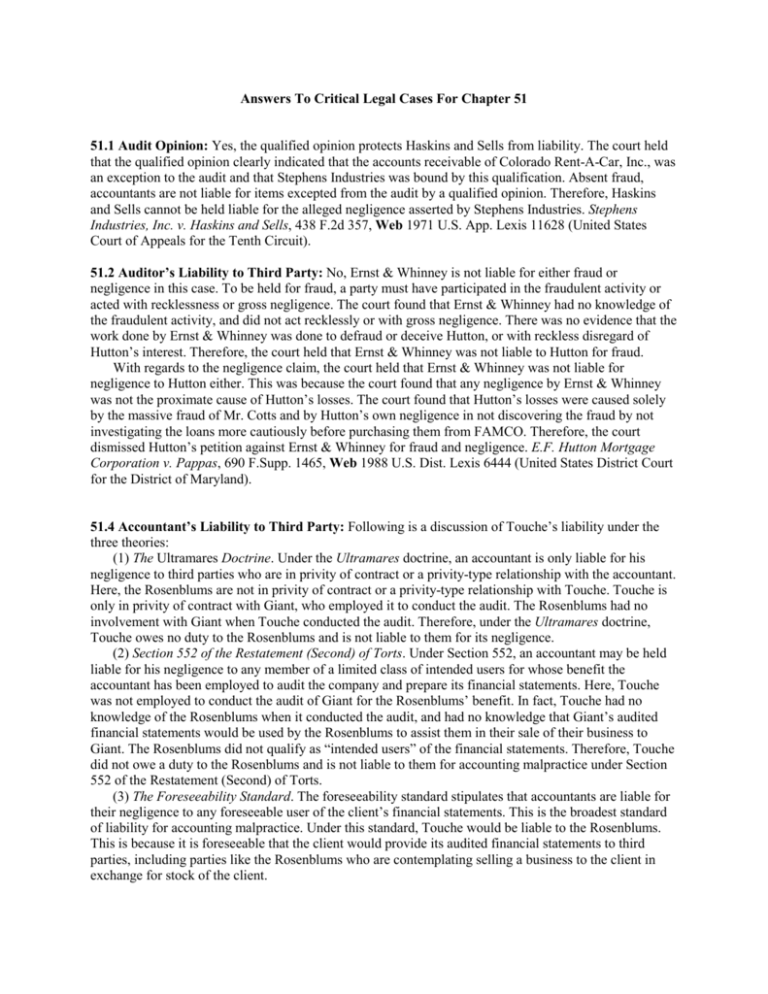

Answers To Critical Legal Cases For Chapter 51 51.1 Audit Opinion: Yes, the qualified opinion protects Haskins and Sells from liability. The court held that the qualified opinion clearly indicated that the accounts receivable of Colorado Rent-A-Car, Inc., was an exception to the audit and that Stephens Industries was bound by this qualification. Absent fraud, accountants are not liable for items excepted from the audit by a qualified opinion. Therefore, Haskins and Sells cannot be held liable for the alleged negligence asserted by Stephens Industries. Stephens Industries, Inc. v. Haskins and Sells, 438 F.2d 357, Web 1971 U.S. App. Lexis 11628 (United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit). 51.2 Auditor’s Liability to Third Party: No, Ernst & Whinney is not liable for either fraud or negligence in this case. To be held for fraud, a party must have participated in the fraudulent activity or acted with recklessness or gross negligence. The court found that Ernst & Whinney had no knowledge of the fraudulent activity, and did not act recklessly or with gross negligence. There was no evidence that the work done by Ernst & Whinney was done to defraud or deceive Hutton, or with reckless disregard of Hutton’s interest. Therefore, the court held that Ernst & Whinney was not liable to Hutton for fraud. With regards to the negligence claim, the court held that Ernst & Whinney was not liable for negligence to Hutton either. This was because the court found that any negligence by Ernst & Whinney was not the proximate cause of Hutton’s losses. The court found that Hutton’s losses were caused solely by the massive fraud of Mr. Cotts and by Hutton’s own negligence in not discovering the fraud by not investigating the loans more cautiously before purchasing them from FAMCO. Therefore, the court dismissed Hutton’s petition against Ernst & Whinney for fraud and negligence. E.F. Hutton Mortgage Corporation v. Pappas, 690 F.Supp. 1465, Web 1988 U.S. Dist. Lexis 6444 (United States District Court for the District of Maryland). 51.4 Accountant’s Liability to Third Party: Following is a discussion of Touche’s liability under the three theories: (1) The Ultramares Doctrine. Under the Ultramares doctrine, an accountant is only liable for his negligence to third parties who are in privity of contract or a privity-type relationship with the accountant. Here, the Rosenblums are not in privity of contract or a privity-type relationship with Touche. Touche is only in privity of contract with Giant, who employed it to conduct the audit. The Rosenblums had no involvement with Giant when Touche conducted the audit. Therefore, under the Ultramares doctrine, Touche owes no duty to the Rosenblums and is not liable to them for its negligence. (2) Section 552 of the Restatement (Second) of Torts. Under Section 552, an accountant may be held liable for his negligence to any member of a limited class of intended users for whose benefit the accountant has been employed to audit the company and prepare its financial statements. Here, Touche was not employed to conduct the audit of Giant for the Rosenblums’ benefit. In fact, Touche had no knowledge of the Rosenblums when it conducted the audit, and had no knowledge that Giant’s audited financial statements would be used by the Rosenblums to assist them in their sale of their business to Giant. The Rosenblums did not qualify as “intended users” of the financial statements. Therefore, Touche did not owe a duty to the Rosenblums and is not liable to them for accounting malpractice under Section 552 of the Restatement (Second) of Torts. (3) The Foreseeability Standard. The foreseeability standard stipulates that accountants are liable for their negligence to any foreseeable user of the client’s financial statements. This is the broadest standard of liability for accounting malpractice. Under this standard, Touche would be liable to the Rosenblums. This is because it is foreseeable that the client would provide its audited financial statements to third parties, including parties like the Rosenblums who are contemplating selling a business to the client in exchange for stock of the client. The Supreme Court of New Jersey adopted the foreseeability standard for judging an accountant’s negligence liability to third parties. The court stated: When the independent auditor furnishes an opinion with no limitation in the certificate as to whom the company may disseminate the financial statements, he has a duty to all those whom that auditor should reasonably foresee as recipients from the company of the statements for its proper business purposes, provided that the recipients rely on the statements pursuant to those business purposes. The court found that the Rosenblums were foreseeable recipients of the financial statements and that they relied on the statements when they made their decision to sell their business to Giant. The court held Touche liable to the Rosenblums for accounting malpractice. Rosenblum v. Adler, 93 N.J. 324, 461 A.2d 138, Web 1983 N.J. Lexis 2717 (Supreme Court of New Jersey). 51.5 Ultramares Doctrine: Following is a discussion of Cooper’s liability under the three theories: (1) The Ultramares Doctrine. Under the Ultramares doctrine, an accountant is only liable for his negligence to third parties who are in privity of contract or a privity-type relationship with the accountant. Here, the Lindner Funds were not in privity of contract or a privity-type relationship with Coopers. Coopers was only in privity of contract with Texscan, its client who employed it to conduct the audit. The Lindner Funds had no involvement with Texscan when Coopers conducted the audit. Under the Ultramares doctrine, Coopers owes no duty to the Lindner Funds and cannot be held liable to them for its alleged negligence. (2) Section 552 of the Restatement (Second) of Torts. Under Section 552, an accountant may be held liable for his negligence to any member of a limited class of intended users for whose benefit the accountant has been employed. Here, Coopers was not employed to conduct the audit of Texscan for the benefit of the Lindner Funds. Coopers did not have knowledge that Texscan’s audited financial statements would be used by the Lindner Funds in making their decision to invest in the company. The Lindner Funds do not belong to a very small group of persons for whose guidance Coopers prepared the financial statements. Therefore, under Section 552 of the Restatement (Second) of Torts, Coopers did not owe a duty to the Lindner Funds and is not liable to them for their alleged negligence. The Missouri Court of Appeals took this middle ground and chose to apply a balancing test to determine whether Coopers could be held liable to the Lindner Funds. The court held that the Lindner Funds did not state a cause of action against Coopers and dismissed the complaint. (3) The Foreseeability Standard. The foreseeability standard stipulates that accountants are liable for their negligence to any foreseeable user of the client’s financial statements. This is the broadest standard of liability for accounting malpractice. Under this standard, Coopers could be held liable to the Lindner Funds for its alleged negligence in preparing the audited financial statements of Texscan. This is because it is foreseeable that potential investors—such as the Lindner Funds—would obtain, review, and rely on the audited financial statements of a company before investing in that company. Thus, under the foreseeability standard, Coopers could be held liable to the Lindner Funds for its alleged negligence in conducting the audit of the Texscan Corporation. Lindner Fund v. Abney, 770 S.W.2d 437, Web 1989 Mo. App. Lexis 490 (Court of Appeals of Missouri). 51.7 Accountant-Client Privilege: Roberts, the client, wins. Chaple, the accountant, was bound by Georgia’s accountant-client privilege. A state’s accountant-client privilege prevents an accountant from disclosing information about a client or becoming a witness against the client in state court proceedings. The court held that the purpose of the state’s accountant-client privilege is to insure an atmosphere wherein the client will transmit all relevant information to his accountant without fear of any future disclosure in subsequent litigation. The court held that Chaple’s voluntary disclosure of the confidential information about Roberts to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), without waiting for a subpoena, violated Georgia’s accountant-client privilege. However, no accountant-client privilege exists under federal law. Thus, Georgia’s accountant-client privilege is inapplicable to federal proceedings not involving state law claims. In this case, the IRS, an agency of the federal government, is investigating Roberts for violation of the Internal Revenue Code, a federal law. Therefore, if the IRS issued an administrative summons or subpoena to Chaple requesting the confidential information about Roberts, the Georgia accountant-client privilege could not be asserted to prevent disclosure of this information to the IRS. Because the IRS could eventually issue such a summons or subpoena in this case, the court held that Roberts suffered minimal, if any, damages. The court reversed the trial court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of Chaple. Roberts v. Chaple, 187 Ga.App. 123, 369 S.E.2d 482, Web 1988 Ga. App. Lexis 554 (Court of Appeals of Georgia).