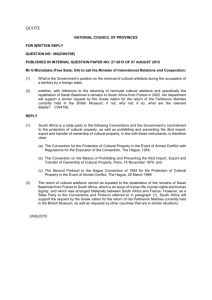

C:\My Documents\Symposium\ip treaty 10

advertisement