Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal

advertisement

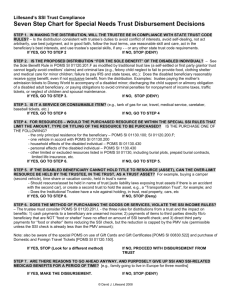

POMS PRODUCTION AND OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT Vol. 14, No. 4, Winter 2005, pp. 442– 449 issn 1059-1478 兩 05 兩 1404 兩 442$1.25 © 2005 Production and Operations Management Society Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal Kenneth K. Boyer • Morgan Swink • Eve D. Rosenzweig Eli Broad Graduate School of Management, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824-1122, USA Eli Broad Graduate School of Management, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824-1122, USA Goizueta Business School, Emory University, 1300 Clifton Road, Atlanta, Georgia 30322-2710, USA boyerk@msu.edu • Swink@bus.msu.edu • Eve_Rosenzweig@bus.emory.edu I n this paper, we examine the operations strategy literature in the POMS journal to determine what has been learned and to suggest new directions for further study in this important area of research. Our review of this literature resulted in the selection of thirty-one relevant articles, many of which draw upon multiple theoretical perspectives. We identify eight such theoretical perspectives, and go on to classify these perspectives in terms of the scope of inquiry employed in the research (focused versus aggregated) and the researcher’s assumptions about choice processes (behavioral versus rational). In doing so, we show that this body of work is dominated by papers that draw upon theoretical perspectives enabling a more holistic scope of inquiry, with a bias towards a view of strategy as a highly rational process. Building on our systematic review and integration of the literature, we suggest multiple areas for future research. Key words: operations strategy; theory development; areas for future research Submissions and Acceptance: Received January 2005; revisions received February 2005; April 2005; accepted May 2005. 1. Introduction 2. Studies of operations strategy have formed a key stream of research in the POMS journal since its founding, including papers from several of the leading strategy researchers. In reviewing this literature stream, we focused on the articles which addressed operations strategy, defined as decisions and plans involving the developing, positioning, and aligning of managerial policies and needed resources so that they are consistent with the overall business strategy (Anderson, Cleveland, and Schroeder 1989; Skinner 1969; Swamidass 1986). This level of planning and decision-making focuses on the competitive operations capabilities of a firm over the long term. Further, an operations strategy integrates various sub-functional activities and relates various functional policies to environmental changes (Schendel and Hofer 1979). In these ways, strategic operations decisions are distinct from tactical planning or operational control (Anthony 1965). Describing the POMS Operations Strategy Research Space We reviewed all papers published to date in the POMS journal for possible inclusion in our analysis of the operations strategy research space. Table 1 summarizes the thirty-one POMS papers we selected as fitting the operations strategy domain, as defined above. The table describes the papers in terms of their topical focus and dominant theoretical perspective(s). We developed these categories based on our review of the papers and the larger operations strategy literature. While several papers address many theoretical perspectives, we limited the classification to, at most, four perspectives that received the most significant treatment. A brief summary of the methodology employed in each paper is also included in Table 1. 2.1. Topical Focus The 31 papers represent two areas of topical focus— content and process—which are broad categories used 442 Boyer, Swink, and Rosenzweig: Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal 443 Production and Operations Management 14(4), pp. 442– 449, © 2005 Production and Operations Management Society Table 1 Chronological Review of Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal Topical focus Article McDougall, Deane & D’Souza (1992) St. John and Young (1992) Hayes (1992) Lefebvre, Langley, Harvey, & Lefebvre (1992) Zahra and Das (1993) Vickery, Droge and Markland (1994) Theoretical perspective Methodology Trade-offs/ Strategic/ Strategic Goal Strategy Strategy cumulative process Positioning/ Strategic evolution/ alignment/ Production content process capabilities choice types RBV fit change consensus theory ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ Data collection/ analysis Sample size Survey Survey Plenary address 64 15 n/a ⴱ Survey Survey 526 149 ⴱ Survey Conceptual Review Conceptual Review Conceptual Review Conceptual Review Conceptual Review Case Study Case Study Survey Case Study Survey ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ Skinner (1996a) ⴱ Skinner (1996b) ⴱ Hayes & Pisano (1996) ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ Clark (1996) Wheelwright & Bowen (1996) Voss & Winch (1996) Benningson (1996) Gupta & Somers (1996) Pesch & Schroeder (1996) Gupta and Lonial (1998) Brush, Maritan, Karnani (1999) Bordoloi, Cooper and Matsuo (1999) Ritzman & Safizadeh (1999) Safizadeh, Ritzman & Mallick (2000) Pagell & Handfield (2000) Sousa & Voss (2001) Dostaler (2001) Boyer & Lewis (2002) ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ Hayes (2002) Heim & Sinha (2002) ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ Ramdas (2003) Jack & Raturi (2003) Lapre & Scudder (2004) Rosenzweig & Roth (2004) Anand & Ward (2004) Total (n) ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ 29 ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ in prior operations strategy reviews (see e.g., Leong, Snyder, and Ward 1990; Swink and Way 1995). Content-focused research refers to the study of operations competitive priorities and capabilities as well as structural (e.g., capacity, technology) and infrastructural (e.g., workforce) choices and configurations. While structural choices refer to “bricks-and-mortar” decisions, infrastructural choices capture the policies and systems for managing the structural components (Hayes and Wheelwright 1984). Process-focused re- 6 ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ 6 ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ 12 ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ 8 ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ 4 ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ ⴱ 12 8 8 ⴱ 5 65 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 15 1 269 24 175 Survey Review and IP Model Survey 167 Survey Case Study Case Study Case Study Survey Conceptual Review Archival Data Conceptual Framework Archival Data Archival Data Survey Survey 144 50 5 2 110 n/a 144 n/a 255 n/a 550 76 81 101 search refers to the study of strategy decision-making and development, communication of strategic decisions within the organization, and strategy implementation. As shown in Table 1, strategy content research has received substantial attention in the POMS literature. While relatively less emphasis has been placed on the study of strategy process, it is particularly important that work has been done in this area over the last decade, given earlier calls for research on strategy processes (Anderson, Cleveland and Schroe- 444 Boyer, Swink, and Rosenzweig: Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal Production and Operations Management 14(4), pp. 442– 449, © 2005 Production and Operations Management Society der 1989; Leong, Snyder, and Ward 1990; Swink and Way 1995). 2.2. Theoretical Perspectives Many researchers have highlighted the importance of identifying and clarifying operations management (OM) theories; they argue that theoretical development has been lacking and is necessary in order for the field to progress (Amundson 1998; Melnyk and Handfield 1998; Schmenner and Swink 1999). As we reviewed the thirty-one articles, a variety of theoretical perspectives became evident. Skinner’s (1969, 1974) seminal articles articulate some of the foundational concepts of operations strategy. Probably the most important and central concern raised in his articles is the need to “link” manufacturing structural and infrastructural decisions with overall business plans, and thus guide business by building capabilities essential to the formulation and achievement of the firm’s overall strategy. Several of the theoretical perspectives represented in the POMS operations strategy articles address this central concern. For example, about one-third of the articles deal with trade-offs among competitive priorities/capabilities such as quality, delivery, flexibility, and cost at the plant and/or business unit level. This has been a major area of debate between the supporters of the proposition that trade-offs are necessary (Bennigson 1996; Boyer and Lewis 2002; Hayes and Wheelwright 1984; Safizadeh, et al. 2000; Skinner 1969; 1996a) versus supporters of a cumulative capabilities model specifying that capabilities can be complementary and built simultaneously over time (Corbett and Van Wassenhove 1993; Ferdows and De Meyer 1990; Noble 1995; Rosenzweig and Roth 2004). A related perspective is strategic/process choice, which reflects the pattern of choices comprising the operating system; articles classified in this category examine multiple structural and infrastructural decision areas. Of the various strategic decision areas, process choice appears to be the most commonly studied area in the POMS journal (see e.g., Ritzman and Safizadeh 1999; Safizadeh, Ritzman, and Mallick 2000). Fundamental technological and market-based factors are thought to constrain operations managers to certain structural and infrastructural configurations. Studies of how these strategic configurations might relate to one another in an overall competitive space address the relative positioning of various operational types, or groups of organizations that are similar in terms of their strategy, and supporting pattern of structural and infrastructural choices (e.g., Lefebvre et al. 1992; McDougall et al. 1992; Zahra and Das 1993). Several POMS studies have sought to empirically un- cover or verify the existence of certain theoreticallygrounded configurations and to establish their relationship to performance (e.g., Heim and Sinha 2002). Along these lines, POMS researchers also draw upon the resourced-based view of the firm (RBV) to link resources and organizational capabilities to performance (Rosenzweig and Roth 2004; Vickery et al. 1994). This theoretical perspective, grounded in the strategic management literature, suggests that competitive advantage results from the extent to which the firm’s set of assets, processes, knowledge, etc., are valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate or substitute (Barney 1991). For other articles in the POMS set, more of an emphasis is placed on theories related to strategic fit (e.g., Anand and Ward 2004; Gupta and Lonial 1998; Gupta and Somers 1996; Pesch and Schroeder 1996; Skinner 1996a, 1996b). Finding its roots in contingency theory, this perspective indicates that certain operations management strategic configurations/forms are more or less appropriate for certain business competitive strategies and environmental contexts (e.g., dynamic environment). All of the theoretical perspectives discussed thus far tend to view operations strategy at relatively high organizational levels, comprising many structural and infrastructural decision areas. They also tend to view strategy as a fairly mechanical process in which managers with extensive rationality seek to make appropriate linkages between strategy, structure, and performance. Other articles in the POMS operations strategy research stream take a more behavioral view. For example, several POMS studies focus on strategic evolution. In this theoretical perspective, researchers are interested in examining how organizations change over time, and how they move from one state to another (e.g., Clark 1996; Hayes and Pisano 1996; Lapre and Scudder 2004; Wheelwright and Bowen 1996). Much of the research in this area is based on the premise that operations strategy is path dependent: the pattern of structural and infrastructural choices made by firms today constrains their choice of future strategic alternatives (Clark 1996; Hayes and Pisano 1996). Yet this perspective can differ from fairly rational views of strategy development processes, with the recognition that evolution may be “guided” by factors that go beyond clear strategic choices, such as the rate at which the organization learns or the influence of a top manager who has his/her own personal agenda. With a few notable exceptions (e.g., Dostaler 2001; Lapre and Scudder 2004), research in this area is primarily conceptual in nature; there is a strong need to empirically examine dynamic models of operations strategy. Another behavioral point of view is that of goal Boyer, Swink, and Rosenzweig: Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal Production and Operations Management 14(4), pp. 442– 449, © 2005 Production and Operations Management Society alignment/consensus among different decision makers within or between organizations (Hayes 1992; St. John and Young 1992; Voss and Winch 1996). This stream of research examines the need for numerous people within a single organization to work in concert to achieve strategic objectives—a critical need since operations, more so than other areas such as finance or marketing—requires the inputs of a large proportion of the organization. A final area of strategy research evidenced in the POMS articles deals with what we term production theory. These studies tend to be more focused on a single aspect of strategy or performance, such as product variety management (e.g., Ramdas 2003) or flexibility (e.g., Jack and Raturi 2003). Furthermore, their primary objectives are to explore or explain the technological bounds and complexities governing the application of a given approach or management paradigm. Some of these studies (e.g., Jack and Raturi 2003) are highly rational or mechanistic in their view of operations, which we refer to as the technical/mechanistic view of production theory. Other studies (e.g., Pagell and Handfield 2000) employ more of a sociotechnical view that incorporates human and organizational behavioral issues associated with the adoption or success of a given operational program. To summarize the existing POMS operations strategy literature, we offer a framework in Figure 1 that maps the various theoretical perspectives on two major dimensions: (1) scope of inquiry employed in the research; and (2) the researcher’s assumptions about choice processes. The scope of inquiry dimension enables us to position the POMS operations strategy papers in terms of the level at which the research questions are addressed/studied. For example, several of the POMS studies deal with structural and infrastructural patterns of aggregate decisions at a high organizational level (e.g., Lefebvre et al. 1992; McDougall et al. 1992; Vickery et al. 1994), while others focus on specific paradigmatic initiatives and their relationships to operations strategy or competitiveness (e.g., Brush, et al. 1999; Sousa and Voss 2001). As depicted in Figure 1, the majority of the POMS operations strategy papers draw upon theoretical perspectives that enable a more holistic or aggregated scope of inquiry. Our second classification dimension—assumptions about choice processes—is derived from a recent review of the business strategy literature (see Gavetti and Levinthal 2004). Like the field of business strategy, the collection of POMS operations strategy papers is characterized by much variation in the “researchers’ assumptions about the nature of individual choice behavior” (Gavetti and Levinthal 2004, 1309). Researchers’ views vary from those characterizing the Figure 1 445 Mapping Theoretical Perspectives of POMS Operations Strategy Research. (NOTE: The number of papers assigned to each theoretical perspective corresponds to the assignments listed in Table 1. Note that papers could be assigned to more than one perspective.) behavior of decision makers as being extensively rational and comprehensive to those that view decision makers’ rationality as being bounded or local at best, thereby acknowledging the potential irrationality of decision makers. As suggested by the foregoing discussion, “behavioral” in this case refers to research perspectives that consider either the highly bounded rationality of individual decision makers, or the sociological and political aspects of managerial decisionmaking. In addition, studies we classify as taking a more behavioral view recognize that managers act upon their perceptions, which may or may not be accurate reflections of reality. Figure 1 indicates that POMS strategy research has a fairly strong bias toward viewing operations strategy as a highly rational process. This seems consistent with the training of OM researchers and their inclination toward a view of organizations as a collection of “processes.” Nonetheless, a few of the studies bring greater attention to “human” behavioral issues (e.g., Dostaler 2001). 2.3. Methodology As noted previously, Table 1 also contains columns showing the primary method of data collection and/or analysis used in each study as well as the sample size (when relevant). To quickly summarize, approximately half of the POMS operations strategy papers employ survey research designs. Of those papers, Table 1 shows that sample sizes have generally increased over the past decade, which is likely a result of an increasing emphasis on eliminating potential sources of bias. The remaining papers comprising Table 1 are predominantly categorized as conceptual Boyer, Swink, and Rosenzweig: Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal 446 Production and Operations Management 14(4), pp. 442– 449, © 2005 Production and Operations Management Society reviews/frameworks and case studies, yet over time, a broader variety of methodologies has gradually been utilized. Heim and Sinha (2002), Jack and Raturi (2003), and Lapre and Scudder (2004), for example, use archival data to investigate their research questions. While there is a general lack of readily available, reliable data in many industries, identifying alternative, innovative sources of data is becomingly increasingly important as survey response rates continue to decline (Klassen and Jacobs 2001; Lapre and Scudder 2004). Finally, we should also note that several studies have focused on measurement issues, especially for ill-defined multidimensional constructs such as factory focus and flexibility (Pesch and Schroeder 1996; Bordoloi et al. 1999; Jack and Raturi 2003). 3. Future Directions Having briefly reviewed the literature, we now offer some future directions for research. These are based on our review of the literature and numerous discussions with colleagues in the area. Our intent is to offer broad suggestions as opposed to an exhaustive list of opportunities. We start with a discussion of research opportunities in the broad domain of operations strategy and then hone in on opportunities tied to Figure 1. 3.1. A Broader View of Strategy Historically, the bulk of operations strategy papers have focused primarily on manufacturing strategy. While there have been numerous calls for broaderbased research, particularly on services and on supply chain as an inter-organizational system, there is still a relative paucity of studies in these areas. Service organizations currently comprise a large proportion of the economies of developed nations. Moreover, as more manufacturing firms try to differentiate themselves based on the services they offer in addition to the tangible products, it becomes increasingly important to examine service strategy. Yet of the collection of POMS operations strategy papers, only three explicitly address service strategy (Hayes 2002; Heim and Sinha 2002; Lapre and Scudder 2004). Suggested topics for examination include strategic linkages between back office and front office activities, the use of IT systems to provide greater capabilities to customers and to reduce workload, and the strategic use of technology in services. In addition to this increased emphasis on service operations, we have also witnessed a surge in interest in supply chain management over the past decade. While a great deal of supply chain research has been generated, a unified framework for defining supply chain strategy has not emerged. Assuming operations strategy is a subset of overall supply chain strategy, research is needed to explain how and when to ex- trapolate from the former to the latter. Giffi, Roth, and Seal (1990), for example, add a set of integration strategy choices to the structural and infrastructural decision areas; these additional choices help define how operations strategically interfaces with both internal (e.g., marketing, R&D) and external (e.g., suppliers, customers) entities. Along these lines, Hayes (2002, 28) suggests that the domain of operations must transition from “products and processes” to “systems of complementary products provided through networks by different organizations.” As a starting point, more studies of operations strategy should extend beyond the manufacturing plant to encompass networks of plants within the strategic business unit (SBU), and ultimately networks that span multiple firms across the supply chain. Specific questions that need to be investigated at these higher organizational levels include: How should supply chain strategy be defined? Is it simply an expansion/re-working of existing operations strategy principles, or do we need an entirely new framework? Related questions include: How do supply chain partners cooperate in jointly developing a strategy— or should they? How do adversarial and cooperative supply chain strategies differ? Finally, are their major drivers of supply chain management, i.e., dominant organizations? 3.2. Resource-Based View The RBV model provides a solid theoretical foundation for understanding the role operations strategy can play in creating and sustaining a competitive advantage. Assembling, integrating, and deploying synergistic tangible (e.g., IT infrastructure) and intangible (e.g., technical know-how) resources may serve as sources of competitive advantage in the form of operations-based capabilities like delivery speed or process flexibility (Bharadwaj 2000). We suggest operations strategy researchers apply this theoretical perspective to two critical areas for future research: the technology/strategy interface and process innovation management. Much of the OM technology-oriented research has focused on antecedents to technology (mostly AMT) adoption and performance benefits. However, there has been less study that takes a broader view of technology as a strategy enabler. For example, the impact of information technology on business over the last 20 years is undeniable, yet true strategic benefits have been difficult to quantify (Brynjolffson 1993). The rush to implement the newest and “best” software/hardware often occurs without much strategic thought, particularly at the supply chain level. As a result, there is a strong need for operations strategy researchers to examine the roles and impacts of technology and related, supporting resources in operations through a Boyer, Swink, and Rosenzweig: Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal Production and Operations Management 14(4), pp. 442– 449, © 2005 Production and Operations Management Society more strategic lens. The information systems (IS) literature may serve as a guide, as many researchers in this field draw upon the RBV to link IS strategy to operational and business performance (see e.g., Bharadwaj 2000). Key OM technology/strategy interface questions that need to be addressed concern the relationship between various competitive priorities and IT applications. For example, numerous companies have employed online ordering or automated telephone systems as a means of lowering cost (fewer call center operators translates to lower cost). However, this savings may come at some price in terms of quality if frustrated customers feel lost in the process. Another key question involves matching IT systems across departments, business units, and supply chains: How should companies use strategy and particular technologies to maximize performance for the entire organization or supply chain rather than individual departments/units? Along these lines, we anticipate that information and communication technologies (ICT) will play an increasingly prominent role in the study of operations strategy—as real-time information becomes more readily available and coordination costs continue to decrease, organizations will rely on supply chain partners to a greater extent to conduct non-core business processes. Important research questions in this context include: Which business processes should be outsourced today, and which should be kept in-house? Clearly those business processes that are valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate should be retained inhouse. Of the outsourced business processes, which should be located domestically and which should be located offshore? How will these decisions change over time? Drilling down on business processes further, process innovation has received much less research attention than product innovation across all business literatures. However, due to recent competitive threats from firms in countries with lower input costs, process innovation is today a potentially important and strategic source of advantage for manufacturing firms located in more industrialized nations. To date, most existing OM research has tended to view operational process innovation as a matter of incremental changes and “continuous improvement.” There is a need to define and study more radical forms of process innovation in operations settings. Further, we need to study process innovation as a manageable portfolio of synergistic resources that work together to create a dynamic capability with strategic potential. 447 3.3. Strategic Evolution/Change Strategic evolution addresses the question of how companies change operations strategy over time. Clearly there is some incremental change, but there are also substantial questions regarding how companies make dramatic or non-incremental changes. Numerous companies and industries are facing or have faced a need to make such changes. Examples include the airline industry (where major carriers are trying to move toward the Southwest model), the automobile industry (where American car manufacturers have been struggling to re-invent themselves for two decades) and the computer industry (where Dell has created a direct model which rivals have not been able to successfully copy). Critical questions to be addressed in this area include: How should companies recognize when they are due for a “non-incremental” change of strategy? How should this strategy be pursued? Research on strategic evolution should seek to examine a few companies in depth over a long period of time in order to document and analyze evolutionary patterns. Operations strategy research in this area would also benefit from an integration of views articulated in industrial organization and business strategy research literatures (e.g., population ecology—Carroll 1988). 3.4. Goal Alignment/Consensus The need for alignment is implicit in almost every study of operations strategy, but has received relatively little explicit examination. Due to an overly rational view of strategic processes, most research studies assume that a company with an appropriate strategy in terms of content and process is well positioned for success, but in truth operational decisions are made with such great frequency by such a large number of individuals within an organization that there is often a high-degree of misalignment. Research needs to be done to address how various groups within a company can be better aligned internally, as well as how external alignment with supply chain partners can be achieved. There are also substantial issues regarding the level of analysis for alignment. For example, traditional competitive priorities of cost, quality, flexibility and delivery can be broadly aligned, yet this may not translate to detailed alignment of specific metrics within each area. In short, there is a strong need to examine alignment by studying multiple respondents within a single organization or supply chain. Furthermore, this sort of study needs to consider behavioral elements of decision processes. For example, social, political and other motivations need to be explicitly considered as possible sources of alignment/misalignment. 448 Boyer, Swink, and Rosenzweig: Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal Production and Operations Management 14(4), pp. 442– 449, © 2005 Production and Operations Management Society 3.5. Production Theory Like goal alignment, future production theory studies would benefit from a consideration of the behavioral elements of decision processes. Further, while not explicitly captured in the POMS operations strategy research space, a large literature within the overall OM research field focuses on production theory and specifically the description and impact of “practice paradigms.” Example practice paradigms include total quality management, six-sigma, and lean manufacturing. While the impacts of these approaches on manufacturing practice and performance are clearly significant, the implications for operations strategy are not well understood. Are practice paradigms strategic? What are the implications for positioning and strategic fit theories? Future research studies need to clarify the boundaries of operations strategy and its relationship to specific practice programs and initiatives. 3.6. Summary We offer these ideas as a starting point for further thought and discussion regarding directions for future research of operations strategy. Overall, operations strategy continues to be rich area, offering many complex questions that are ripe for research. Acknowledgments We thank the referees and the Editor-in-Chief for their valuable comments, which have considerably improved the paper. References Amundson, S. D. 1998. Relationships between theory-driven empirical research in Operations Management and other disciplines. Journal of Operations Management 16(4) 341–359. Anand, G., P. Ward. 2004. Fit, flexibility and performance in manufacturing: Coping with dynamic environments. Production and Operations Management 13(4) 369 –385. Anderson, J. C., G. Cleveland, R. Schroeder. 1989. Operations strategy: A literature review. Journal of Operations Management 8(2) 133–158. Anthony, R. N. 1965. Planning and control systems: A framework for analysis. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17(1) 99 –120. Bennigson, L. A. 1996. Changing manufacturing strategy. Production and Operations Management 5(1) 91–102. Bharadwaj, A. S. 2000. A resource-based perspective on information technology capability and firm performance: An empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly 24(1) 169 –196. Brush, T. H., C. A. Maritan, A. Karnani. 1999. The plant location decision in multinational manufacturing firms: An empirical analysis of international business and manufacturing strategy perspectives. Production and Operations Management 8(2) 109 – 132. Brynjolffson, E. 1993. The productivity paradox of information technology. Communications of the ACM 36(12) 67–77. Bordoloi, S. K., W. W. Cooper, H. Matsuo. 1999. Flexibility, adaptability, and efficiency in manufacturing systems. Production and Operations Management 8(2) 133–150. Boyer, K. K., M. W. Lewis. 2002. Competitive priorities: Investigating the need for trade-offs in operations strategy. Production and Operations Management 11(1) 9 –20. Carroll, G. 1988. Ecological models of organizations. Ballanger Books, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Clark, K. B. 1996. Competing through manufacturing and the new manufacturing paradigm: Is manufacturing strategy passe? Production and Operations Management 5(1) 42–58. Corbett, C., L. van Wassenhove. 1993. Trade-offs? What trade-offs? Competence and competitiveness in manufacturing strategy. California Management Review 35(4) 107–122. Dostaler, I. 2001. Beyond practices: A qualitative inquiry into high performance electronics assembly. Production and Operations Management 10(4) 478 – 493. Ferdows, K., A. De Meyer. 1990. Lasting improvements in manufacturing performance: In search of a new theory. Journal of Operations Management 9(2) 168 –184. Gavetti, G., D. A. Levinthal. 2004. The strategy field from the perspective of Management Science: Divergent strands and possible integration. Management Science 50(10) 1309 –1318. Giffi, C., A. V. Roth, G. M. Seal. 1990. Competing in world-class manufacturing: America’s 21st century challenge. Richard D. Irwin, Inc., Homewood, Illinois. Gupta, Y. P., T. M. Somers. 1996. Business strategy, manufacturing flexibility, and organizational performance relationships: A path analysis approach. Production and Operations Management 5(3) 204 –233. Gupta, Y. P., S. C. Lonial. 1998. Exploring linkages between manufacturing strategy, business strategy, and organizational strategy. Production and Operations Management 7(3) 243–264. Hayes, R. H., S. C. Wheelwright. 1984. Restoring Our Competitive ed.ge: Competing Through Manufacturing. John Wiley and Sons, New York, New York. Hayes, R. H. 1992. Production and operations management’s new requisite variety. Production and Operations Management 1(3) 249 –253. Hayes, R. H., G. P. Pisano. 1996. Manufacturing strategy: At the intersection of two paradigm shifts. Production and Operations Management 5(1) 25– 41. Hayes, R. H. 2002. Challenges posed to Operations Management by the “new economy.” Production and Operations Management 11(1) 21–32. Heim, G. R., K. K. Sinha. 2002. Service process configurations in electronic retailing: A taxonomic analysis of electronic food retailers. Production and Operations Management 11(1) 54 –74. Jack, E. P., A. S. Raturi. 2003. Measuring and comparing volume flexibility in the capital goods industry. Production and Operations Management 12(4) 480 –501. Klassen, R., J. Jacobs. 2001. Experimental comparison of web, electronic and mail survey technologies in Operations Management. Journal of Operations Management 19(6) 713–728. Kriimer, F. J., M. E. Hafsi, S. X. Bai. 1997. Production flow control for a manufacturing system with flexible routings. Production and Operations Management 6(1) 37–56. Lapre, M. A., G. D. Scudder. 2004. Performance improvement paths in the U.S. airline industry: Linking trade-offs to asset frontiers. Production and Operations Management 13(2) 123–134. Lefebvre, L.A., A. Langley, J. Harvey, E. Lefebvre. 1992. Exploring the strategy-technology connection in small manufacturing firms. Production and Operations Management 1(3) 269 –285. Leong, G. K., D. Snyder, P. Ward. 1990. Research in the process and content of manufacturing strategy. Omega 18(2) 109 –122. McDougall, P. P., R. H. Deane, D. E. D’Souza. 1992. Manufacturing strategy and business origin of new venture firms in the com- Boyer, Swink, and Rosenzweig: Operations Strategy Research in the POMS Journal Production and Operations Management 14(4), pp. 442– 449, © 2005 Production and Operations Management Society puter and communications equipment industries. Production and Operations Management 1(1) 53– 69. Melnyk, S. A., R. B. Handfield. 1998. May you live in interesting times . . . The emergence of theory-driven empirical research. Journal of Operations Management 16(4) 311–319. Noble, M. A. 1995. Manufacturing strategy: Testing the cumulative model in a multiple country context. Decision Sciences 26(5) 693–721. Pagell, M., R. Handfield. 2000. The impact of unions on operations strategy. Production and Operations Management 9(2) 141–157. Pesch, M. J., R. G. Schroeder. 1996. Measuring factory focus: An empirical study. Production and Operations Management 5(3) 234 –254. Ramdas, K. 2003. Managing product variety: An integrative review and research directions. Production and Operations Management 12(1) 79 –101. Ritzman, L. P., H. H. Safizadeh. 1999. Linking process choice with plant-level decisions about capital and human resources. Production and Operations Management 8(4) 374 –392. Rosenzweig, E. D., A.V. Roth. 2004. Towards a theory of competitive progression: Evidence from high-tech manufacturing. Production and Operations Management 13(4) 354 –368. Safizadeh, H. H., L. P. Ritzman, D. Mallick. 2000. Revisiting alternative theoretical paradigms in manufacturing strategy. Production and Operations Management 9(2) 111–140. Schendel, D., C. W. Hofer. 1979. Strategic management: A new view of business policy and planning. Little Brown, Boston, Massachusetts. Schmenner, R., M. Swink. 1999. On theory in Operations Management. Journal of Operations Management 17(1) 97–113. 449 Skinner, W. 1969. Manufacturing: Missing link in corporate strategy. Harvard Business Review 47(3) 136 –145. Skinner, W. 1996a. Manufacturing strategy on the ‘S’ curve. Production and Operations Management 5(1) 3–14. Skinner, W. 1996b. Three yards and a cloud of dust: Industrial management at century end. Production and Operations Management 5(1) 15–24. Sousa, R., C. A. Voss. 2001. Quality management: Universal or context dependent. Production and Operations Management 10(4) 383– 404. St. John, C. H., S. T. Young. 1992. An exploratory study of patterns of priorities and trade-offs among operations managers. Production and Operations Management 1(2) 133–150. Swamidass, P. M. 1986. Manufacturing strategy: Its assessment and practice. Journal of Operations Management 6(4) 471– 484. Swink, M., M. Way. 1995. Manufacturing strategy: Propositions, current research, renewed directions. International Journal of Operations and Production Management 15(7) 4 –26. Vickery, S. K., C. Droge, R. E. Markland. 1994. Strategic production competence: Convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity. Production and Operations Management 3(4) 308 –318. Voss, C. A., G. W. Winch. 1996. Including engineering in operations strategy. Production and Operations Management 5(1) 78 –90. Wheelwright, S. C., H. K. Bowen. 1996. The challenge of manufacturing advantage. Production and Operations Management 5(1) 59 –77. Zahra, S.A., S. R. Das. 1993. Innovation strategy and financial performance in manufacturing companies: An empirical study. Production and Operations Management 2(1) 15–37.