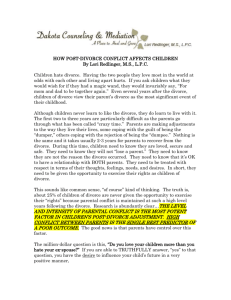

Cultural-community Divorce and the Family Law Act 1975

advertisement