Our Divorce Culture: A Durkheimian Perspective

advertisement

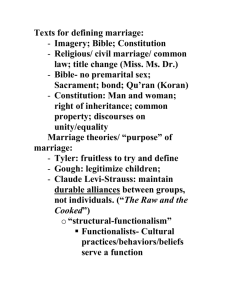

Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 52:147–163, 2011 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1050-2556 print/1540-4811 online DOI: 10.1080/10502556.2011.556962 Our Divorce Culture: A Durkheimian Perspective SCOTT MELTZER Centre College, Danville, Kentucky, USA Comparative studies of children from divorced and intact families consistently find that children of divorced marriages have more short- and long-term psychological and social issues than children from intact marriages. This has led to the need for an evaluation of our divorce culture. The purpose of this research is to analyze the general population’s attitudes on divorce involving children by gender, race, age, socioeconomic status, and participation in religious activities to see if our opinion of divorce is corresponding to the reality of its effect on children. Research-based divorce education programs have been shown to produce positive results in social and psychological readjustment for both children and adults. The findings of this study allow research-based divorce education programs to identify where to focus their services for children and adults. In addition, these findings support the implementation of policy to mandate the development of research-based divorce education programs in each state. KEYWORDS children, divorce, Durkheim, policy According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of divorced people more than quadrupled from 4.3 million in 1970 to 19.3 million in 1997. Seventy percent of divorces involve children (Block, Block, & Gjerde, 1986). In the United States today, 25% of people between 18 and 44 years old have parents who are divorced (Wallerstein, Lewis, & Blakeslee, 2000). Research consistently finds that children of divorce experience negative short- and long-term psychological and social effects, including depression, anger management problems, decline in academic performance, and trust This article does not reflect the views or opinions of City Year or AmeriCorps. Address correspondence to Scott Meltzer, Program Manager, City Year San Antonio, 109-B North San Saba, San Antonio, TX 78207, USA. E-mail: smeltzer@cityyear.org 147 148 S. Meltzer issues (Marquardt, 2005; Wallerstein et al., 2000). The research calls into question the social attitudes and legal policies surrounding divorce and the divorce culture in the United States. Although our society values marriage as a lifelong commitment and couples explain they plan to work hard to stay together, many couples still recognize the possibility that their marriage might not work out (Furstenberg & Cherlin, 1991). Many people know the commonly cited statistic that almost half of all marriages currently end in divorce in the United States (National Center for Health Statistics, 2006). Forty years ago, divorce was not statistically common, in part because cultural attitudes and legal obstacles discouraged divorce. Until the 1960s and 1970s, only adultery and abandonment provided legal exits to marriage (Wallerstein et al., 2000). In the 1960s, however, attitudes toward marriage began to change. In 1969, California passed the Family Law Act, allowing either spouse to obtain a divorce simply due to irreconcilable differences (also known as no-fault divorce; Furstenberg & Cherlin, 1991). By 1985, every state allowed no-fault divorce. The shift in divorce law and passage of no-fault divorce legislation led some to argue that “silently and unconsciously, we created a culture of divorce” (Wallerstein et al., p. 295). Lawmakers continue to debate whether returning to fault as a basis for divorce would reduce the number of divorces each year and thus improve the well-being of children. For example, in February 2009, the Montana House Judiciary Committee introduced a bill that would restore fault divorce and, among other provisions, mandate that a couple go through counseling before a divorce could be granted. Montana has been a no-fault divorce state since 1970, a law that according to the bill, “created a divorce culture to the detriment of children” (H. 419, 2009). The bill continues, “Montana has a compelling interest in reforming no-fault divorce law with the intent of supporting the long-term stability and happiness of marriage and thus the health, safety, and general welfare of children” (H. 419). As a representation of the dispute over whether reestablishing fault divorce would benefit the institution of marriage, the bill died in committee with a tie vote. Some argue that women’s changing roles in society, and in the family in particular, can partially explain the rise in the U.S. divorce rate. First, women’s increased participation in the workforce has decreased their financial dependence on husbands, giving them more freedom to leave a bad marital situation than in years past. Second, the two-career family—a financial necessity for most American families today—has placed increasing demands on men’s and women’s time at work and at home. Expectations about division of housework and child care have changed, but not without difficulties. Durkheim might argue that the shift in women’s employment status has resulted in a change in attitudes toward divorce involving children due to the stress and responsibilities associated with the Our Divorce Culture 149 workplace and childrearing. Although attitudes toward divorce involving children have changed, there is little research on the predictors of these attitudes (Thornton, 1985). The purpose of this research is to analyze the general population’s attitudes on divorce involving children by gender, race, age, socioeconomic status, and participation in religious activities to see if our opinion of divorce is corresponding to the reality of its effect on children. LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK Parents who divorce separate from couplehood to form two separate identities; their children remain the connection that binds them together. Children of divorce essentially live between two worlds (Marquardt, 2005), and divorce creates a permanent identity for children. Wallerstein et al. (2000) heard thousands of adult children of divorce say, “I am a child of divorce” (p. 63). Divorce “leaves a permanent stamp” when it occurs in childhood, because the child is young and impressionable and the effects are felt throughout life (Wallerstein et al., p. 63). Comparative studies of children from divorced and intact families indicate children of divorced families have more short- and long-term psychological and social issues than children from intact families. Until the research of Wallerstein et al. (2000), the 25-year landmark and longest close-up study of divorce ever conducted, and Marquardt (2005), the first nationally representative survey of young adults from divorced families, no researchers had directly compared the experiences of children raised in a divorced family with those raised in an intact family. Both researchers found divorce to be the cause of long-term behavioral and emotional problems, learning problems, increased school dropout rates, early sexual behavior, incidence of divorce, physical illness, and negative religious and spiritual feelings (Kelly & Emery, 2003; Marquardt; Ross & Mirowsky, 1999; Wallerstein et al.). Children of divorce are at least two times more likely to have behavioral, social, and academic problems than children from intact families (Kelly & Emery). Divorce also alters the psychosocial development of youth and results in a “sleeper effect” (i.e., its worst symptoms often appear when children of divorce leave home; Marquardt). As one interviewee of Marquardt’s study said, “The impact of divorce did not diminish soon after our parents split apart but continued to shape us well into adulthood” (p. 54). The worst effects of a divorce occur when young adults of divorce create an identity separate from their parents and attempt to form intimate relationships and families of their own (Marquardt, 2005). They have difficulties due to trust issues and the lack of a framework as to what a 150 S. Meltzer loving and successful marriage looks like. Young adults from divorced families have a more difficult time finding love than those from intact families because they do not have the “inner images of a man and a woman in a stable relationship, only the memories of their parents’ failure to sustain a marriage” (Wallerstein et al., 2000, p. 299). In fact, young adults from divorced families often search for partners who were raised in stable, intact families to fill a void in their own family history (Wallerstein et al.). These adults tend to distance themselves from their own parents and develop a close relationship with their spouse’s family to allow their children to be in an environment of stability and care. Religion is an important component of divorce research because social relationships, such as those made in a religious community, promote a positive recovery from divorce. Religion is a crucial component of research on divorce because the types of social network relationships found in religious communities promote a positive adjustment to divorce (Krumrei, Coit, Martin, Fogo, & Mahoney, 2007). Social network relationships facilitate coping, well-being, overall happiness, and life satisfaction (Krumrei et al., 2007). According to Krumrei et al., “being part of a network, such as a church community, may help divorcing individuals to mobilize specific strengths that promote personal growth in the face of divorce” (p. 160). Our divorce culture, however, has negatively impacted religiosity. According to Marquardt (2005), a young adult’s belief in God and religious teachings, and his or her affiliation with religious institutions, are strongly affected by parents’ divorce. Children of divorce struggle to experience spirituality and faith due to trust issues. In Marquardt’s study, two thirds of young adults who regularly attended a church or synagogue during their parents’ divorce reported that no one from the clergy or congregation reached out to them to offer support. As a result, children of divorce feel less religious and participate less in religious services than those from intact families (Marquardt). Studies suggest that the sanctity of marriage and adherence to religious doctrine used to be a powerful social force in preventing the dissolution of marriage but the influence of religion in recent years has weakened (Nakonezny, Shull, & Rodgers, 1995; Thornton, 1985). Meltzer (2009) found that religiosity, as measured by frequency of religious service attendance, helped predict attitudes toward divorce involving children; as respondents’ frequency of religious service attendance increased, support for divorce involving children decreased. There is a division among denominations of Christianity regarding the acceptance of divorce. Traditionally, Evangelical churches are more willing than mainline Protestant or Catholic churches to talk about divorce and are more likely to have welcoming ministries for separated or divorced people (Marquardt, 2005; Thornton). This research builds on these studies by examining participation in religious activities outside of worship as a measure of religious involvement. Our Divorce Culture 151 Research indicates the marriages of well-educated people might be at a lower risk of divorce because the couple holds greater interpersonal communication skills, maturity, and access to higher occupational statuses and resources that benefit a marriage (Bumpass & Sweet, 1972; Heaton, 1991). However, Meltzer (2009) found that level of education completed was not a good predictor of attitudes toward divorce involving children. Specifically, analysis of General Social Survey data revealed that well-educated people were more likely to support divorce in a bad marriage involving children than less educated people. Thus, Meltzer’s findings suggest that increased education reduces the likelihood of divorce but increases support for divorce in cases of a bad marriage with children. This study examines attitudes of divorce involving children by also considering the role of gender, race, socioeconomic status, age, and participation in religious activities in shaping attitudes toward divorce. Divorce has become a shared experience in our culture because it shapes the lives of many children and reflects our collective values (Marquardt, 2005; Wallerstein et al., 2000). Durkheim’s theory of functionalism provides a theoretical framework for understanding how current gender roles within society and in family life have put strain on the institution of marriage (see Grana, Ollenburger, & Nicholas, 2002). The shift from the collective conscious in primitive society to a division of labor (or specialization of work) in modern society might help explain the shift in men’s and women’s responsibilities in the home, childrearing, and work. Today, both men and women want to have a successful career while also raising a family. Research on two-career marriages reveals high stress and conflict in middleand upper class marriages with couples who try to balance their careers, responsibilities at home, and the upbringing of children. Hochschild (2003) refers to this as the “stalled revolution” because dual-wage-earner families have become the social norm; however, the balance between family life and the workplace has not been adjusted to support the dual-wage-earner family. Mothers and wives want to pursue successful careers just as fathers and husbands do, but they get the bulk of the “second shift” of caring for the home and children. Although women have gained social status in the workforce, the division of labor in our organic society has broken social solidarity and created divisions within marriages. Durkheim might argue that the division of labor (or specialization of work) within society gets repeated within family life. Stress develops and builds within a marriage when mothers and fathers both want fulfilling careers but disagree about the division of home and child care responsibilities. The lack of egalitarian relationships between mothers and fathers contributes to the stress that leads to divorce (Kimmel, 2000). Our society has not created viable services to help parents and children cope with the stress of divorce during and after the event. As Wallerstein et al. (2000) stated, “We continue to foster the myth that divorce is a transient crisis and that as soon as adults reestablish their lives, the children will 152 S. Meltzer fully recover” (p. 302). Although divorce education programs for parents and children have increased nationwide in the past decade to provide counseling, education, and mediation for divorced families, they are usually limited to one to two sessions in the court system and four to six sessions in the community (Kelly & Emery, 2003). In addition, the outcome typically measured is the likelihood the couple returns to court, with a return meaning an unsuccessful outcome and a nonreturn meaning a successful outcome. Research-based divorce education programs, designed to help children with adjustment during and after the divorce, have demonstrated positive behavioral and psychological results in both parents and children (Kelly & Emery). For example, Families in Transition is a research-based divorce education program in Kentucky that provides support to parents and children coping with the psychological and social effects of divorce. The program focuses on reducing a child’s psychological and behavioral problems, recognizing parental conflict and how conflict impacts a child’s development, communicating effectively, and responding appropriately to children’s divorce-related concerns. The combination of effective research-based divorce education programs and comprehensive research on the attitudes toward divorce involving children might help guide the design and implementation of social service programs. These services would address the current population of divorced children and adults. My hypotheses are that men will be more supportive of divorce involving children than women and those who participate in religious activities will be less supportive of divorce involving children than those who do not participate in religious activities. METHOD The data for this study come from the General Social Survey conducted by the National Opinion Research Council. The data were collected through surveys of noninstitutionalized adults in the United States from 1972 to 2006. The data were analyzed using frequency tables, cross-tabulations, Gamma, chi-square, and multiple regression. The independent variables used for the study were sex, race, opinion of family income, age, and participation in religious activities. Respondents were asked for their sex. The possible responses were 1 (male) and 2 (female). The variable was recoded into a dummy variable “being male,” where 1 was male and 0 was female. Respondents were asked, “What race do you consider yourself?” The possible responses were 1 (White), 2 (Black), and 3 (other). The variable was recoded into a dummy variable “being White,” where 1 is White, 0 is Black, and 0 is other. Respondents were asked, “Compared with American families in general, would you say your family income is far below average, below average, average, above average, 153 Our Divorce Culture or far above average?” The possible responses were 1 (far below average), 2 (below average), 3 (average), 4 (above average), and 5 (far above average). Respondents were asked for their age. The possible responses were 18 through 89 or older. For the crosstabs, response categories were recoded to collapse 18 to 25 years to 1, 26 to 35 years to 2, 36 to 45 years to 3, 46 to 55 years to 4, and 56 years and older to 5. Respondents were asked “Do you take part in any of the activities or organizations of your church (synagogue) other than attending service?” The responses were 1 (yes) and 2 (no). The dependent variable used was opinion of support for divorce in a troubled marriage involving children. Respondents were asked, “When a marriage is troubled and unhappy, do you think it is generally better for children if the couple stays together or gets divorced?” The possible responses were 1 (much better to divorce), 2 (better to divorce), 3 (worse to divorce), and 4 (much worse to divorce). RESULTS The univariate analysis on sex reports that 44% of respondents are male and 56% are female (see Table 1). Thus, a majority of respondents are female. The univariate analysis on race reports 82% are White, 13.8% are Black, and 4% are other (see Table 2). Thus, a majority of respondents are White. The univariate analysis on opinion of family income reports 5% of respondents believe their income is far below average, 24% believe their income is below average, 51% believe their income is average, 19% believe their income is above average, and 2% believe their income is far above average (see Table 3). Thus, half of respondents believe their income is average. The univariate analysis on age reports a mean of 45.4 years and a standard deviation of 17.4 years. The univariate analysis on participation in church activities reports 46% of respondents participate in church activities and 54% do not participate in church activities (see Table 4). Thus, a majority of respondents do not participate in church activities. These variables were analyzed to measure their respective impact on the opinion of support for TABLE 1 Frequency Table for Respondents’ Sex Distribution 1: Male 2: Female Total 44.0% (22,439) 56.0% (28,581) 100% (51,020) 154 S. Meltzer TABLE 2 Frequency Table for Race of Respondents Distribution 1: White 2: Black 3: Other Total 81.9% (41,764) 13.8% (7,033) 4.4% (2,223) 100% (51,020) TABLE 3 Frequency Table for Opinion of Family Income Distribution 1: Far below average 2: Below average 3: Average 4: Above average 5: Far above average Total 5.3% (2,438) 23.6% (10,909) 50.6% (23,363) 18.5% (8,536) 1.9% (898) 100% (46,144) TABLE 4 Frequency Table for Participation in Church Activities Distribution 1: Yes 2: No Total 45.9% (408) 54.1% (480) 100% (888) divorce involving children. The univariate analysis on the opinion of support for divorce involving children in a bad marriage indicates that 22% of respondents believe it is much better to divorce when a marriage is troubled and unhappy, 50% believe it is better to divorce, 18% believe it is worse to divorce, and 10% believe it is much worse to divorce (see Table 5). Thus, half of respondents believe it is better for a troubled marriage involving children to result in a divorce. 155 Our Divorce Culture TABLE 5 Frequency Table for Children Better If Bad Marriage Ended by Divorce Distribution 0: Much better to divorce 22.2% (238) 50% (536) 18.1% (194) 9.8% (105) 100% (1,073) 1: Better to divorce 2: Worse to divorce 3: Much worse to divorce Total TABLE 6 Cross-Tabulation of Respondents’ Sex and Children Better If Bad Marriage Ended by Divorce Sex 1: Male 2: Female Total 0: Much better to divorce 1: Better to divorce 2: Worse to divorce 18.0% (84) 25.4% (154) 22.2% (238) 44.0% (205) 54.5% (331) 50.0% (536) 26.0% (121) 12.0% (73) 18.1% (194) 4: Much worse to divorce Total 12.0% (56) 8.1% (49) 9.8% (105) 100% 100% 100% (1,073) The first bivariate analysis on support for divorce involving children in a bad marriage and sex indicates 18% of male respondents and 25% of female respondents believe it is much better to divorce if a troubled marriage involves children. Forty-four percent of male respondents and 55% of female respondents believe it is better to divorce if a troubled marriage involves children. Twenty-six percent of male respondents and 12% of female respondents believe it is worse to divorce if a troubled marriage involves children. Twelve percent of male respondents and 8% of female respondents believe it is much worse to divorce if a troubled marriage involves children (see Table 6). Thus, female respondents tend to believe, more so than male respondents, that it is better for a bad marriage involving children to end by divorce or support the idea of a divorce for a bad marriage. The Gamma for respondents’ sex and support for divorce involving children is 0.276, which indicates a moderately strong association. The chi-square for the two variables is 44.796 with a p value of .00, which indicates the moderately strong association is statistically significant and not likely due to chance. These results suggest that sex is a good predictor of attitudes toward divorce involving children and does not support my hypothesis. The second bivariate analysis on support for divorce involving children in a bad marriage and respondents’ participation in church activities indicates 156 S. Meltzer 17% of respondents who participate in church activities and 22% who do not participate in church activities believe it is much better to divorce if a marriage is troubled and involves children. Forty-eight percent of respondents who participate in church activities and 51% who do not participate in church activities believe it is better to divorce if a marriage is troubled and involves children. Twenty-five percent of respondents who participate in church activities and 17% who do not participate in church activities believe it is worse to divorce if a marriage is troubled and involves children. Eleven percent of respondents who participate in church activities and 9% who do not participate in church activities believe it is much worse to divorce if a marriage is troubled and involves children (see Table 7). Thus, respondents who do not participate in church activities tend to believe more so than respondents who do participate in church activities that it is better for a bad marriage involving children to end by divorce or support the idea of a divorce for a bad marriage. The Gamma for participation in church activities and support for divorce involving children is, 0.162, which indicates a moderately strong association. The chi-square for the two variables is 7.539 with a p value of .057, which indicates the moderately strong association is technically not statistically significant and likely due to chance but within 0.007 from being statistically significant. This could be due to a small sample size (N = 634). These results suggest that participation in church activities is not a good predictor of attitudes toward divorce involving children, although this will be tested again in the multiple regression analysis. The regression model analyzed the overall impact of gender, age, race, socioeconomic status, and participation in church activities on support for divorce in a bad marriage involving children (see Table 8). The coefficient for gender is 0.407, which indicates that the effect of being male on attitudes toward divorce is a 0.407 decrease in support for divorce (because divorce is reverse coded), controlling for the other variables in the model. This coefficient had a p value of .00, which indicates the effect of being male on support for divorce involving children is statistically significant. The coefficient for age is 0.006, which indicates that as age increases by one unit, support for divorce involving children increases by 0.006, controlling for the other variables in the model. This coefficient had a p value of .001, TABLE 7 Cross-Tabulation of Participation in Church Activities and Children Better If Bad Marriage Ended by Divorce Church Attendance 1: Yes 2: No Total 0: Much better 1: Better to to divorce divorce 16.5% (49) 22.3% (75) 19.6% (124) 48.1% (143) 51.3% (173) 49.8% (316) 2: Worse to 4: Much worse divorce to divorce 24.6% (73) 17.2% (58) 20.7% (131) 10.8% (32) 9.2% (31) 9.9% (63) Total 100% 100% 100% (634) 157 Our Divorce Culture TABLE 8 Regression Coefficients Estimating the Effect of Gender, Race, Opinion of Family Income, Age, and Participation in Religious Activities on Attitudes Toward Kids Better If Bad Marriage Ended by Divorce Independent variables Model 1 b Gender (1 = male) Age Participation in church activities Race (1 = White) Opinion of family income Intercept/constant F R2 0.407∗∗ 0.006∗∗ −0.188∗ −0.053 0.005 2.001 16.204∗∗ 0.072 Note. Data from General Social Survey 1972–2006. ∗ p < .01. ∗∗ p < .001. which indicates the effect of age on support for divorce involving children is statistically significant. The coefficient for participation in church activities is −0.188, which indicates that participation in church activities decreases support for divorce involving children by 0.188, controlling for the other variables in the model. This coefficient had a p value of .005, which indicates that participation in church activities has a statistically significant effect on support for divorce involving children. The coefficient for race is −0.053, which indicates that the effect of being White on attitudes toward divorce is a 0.053 decrease in support for divorce, controlling for the other variables in the model. This coefficient had a p value of .984, which indicates the effect of being White on support for divorce involving children is not statistically significant. The coefficient for socioeconomic status, as measured by opinion of family income, is 0.005, which indicates that as opinion of family income increases by one unit, support for divorce involving children increases by 0.005, controlling for the other variables in the model. This coefficient had a p value of .977, which indicates the effect of socioeconomic status on support for divorce involving children is not statistically significant. Thus, only gender, age, and participation in religious activities are good predictors of attitudes toward divorce involving children. The F value of 16.204 with a p value of .00 indicates that the model with only gender, age, and participation in church activities is significant in predicting attitudes toward divorce involving children. The R 2 value is 0.072, which suggests that 7.2% of the variance in opinion of support for divorce involving children is explained by gender, age, socioeconomic status, race, and participation in church activities. DISCUSSION The bivariate and multiple regression analyses do not support my hypothesis that men will be more supportive of divorce involving children then 158 S. Meltzer women. The multiple regression analysis indicates being male decreases the support for divorce involving children. The bivariate analysis indicates women are more supportive of divorce involving children than men. This attitude toward divorce could be explained by the increased social and economic status of women from the women’s rights movement. The financial independence women have gained has allowed them to no longer be tied to the income of men. In addition, no-fault divorce is a reflection of the increased social status of wives. No-fault divorce allows a wife to initiate a divorce decree for irreconcilable differences without the approval of her husband. The increase in social and economic status of women has also changed the family structure. The greatest social change to family structure has been the entry of women into the workplace (Kimmel, 2000). Hochschild (2003) said some families are stalled with women now working outside the home as both an economic necessity and for their own ambition and life goals. Working mothers report higher levels of self-esteem and less depression than housewives, but also report lower levels of marital satisfaction than housewives (Kimmel). Durkheim’s theory of functionalism provides a theoretical framework to suggest why the women in this study report more support of divorce involving children than men. Men’s participation in responsibilities of the home and childrearing has been “surprisingly resistant to change” (Kimmel, p. 147). Just as the source of order in society has shifted from a collective consciousness (i.e., system of shared values and beliefs) to a division of labor (i.e., specialization of work), the modern home, too, has shifted to a division of labor. The modern home has been divided into zones. Research suggests that men are responsible for the outside and women are responsible for the inside, including childrearing (Kimmel). Durkheim would argue the shift from the collective consciousness to the division of labor in families is still in transition (or stalled as Hochschild would argue). The division of labor in families is not balanced and is also gendered, leaving women doing the bulk of the “second shift” (Hochschild). The division within the household has put a strain on marriage. Specifically, women must balance the “second shift” in addition to the responsibilities of their career (Hochschild). Just as fathers and husbands, mothers and wives want to pursue successful careers but they get the bulk of the “second shift” of caring for the home and children. Equal responsibility in the household and childrearing responsibilities would strengthen marriages. Gender equality in the family would not require “men to become more like women” (Kimmel, p. 173). If women can enter the workplace without becoming “masculinized,” it is possible for men to participate in the responsibilities of the home and childrearing without becoming “feminized” (Kimmel). Family life needs to return, as Durkheim would argue, to a collective consciousness between career and family. Some researchers believe the increase in women’s status in the workplace will cause a shift by men in their contribution to responsibilities Our Divorce Culture 159 of the home and children (Kimmel). For example, “as wives are employed longer hours, identify more with their jobs, and provide a larger share of family income, men will do increasing amounts of housework” (Kimmel, p. 174). The findings indicate women are more supportive of divorce involving children than men. Women’s greater support for divorce involving children than men is interesting because women tend to endure a more traumatic experience from divorce. Divorced couples are “likely to suffer at least some amount of personal disorganization, anxiety, unhappiness, loneliness, and low work efficiency” (Albrecht, 1980, p. 61). However, men and women experience divorce differently, particularly in the areas of stress, property settlements, social participation, and income (Albrecht). Divorce is “perceived more traumatic by women than by men” (Albrecht, p. 62). Before a divorce, the majority of a woman’s social life involves couple-oriented activities and after a divorce a woman becomes the “extra person,” which is usually uncomfortable (Albrecht). As a result, the family becomes a more important source of social support following the divorce. Women lose extensive financial support after a divorce because “pre-divorce reports are usually based on the husband’s or combined husband-wife’s income” (Albrecht, p. 65). Women have become financially independent, but their unequal pay in the workforce continues to hurt their postdivorce recovery as they establish their own lives. The findings reported here, however, do support my hypothesis that those who participate in religious activities will be less supportive of divorce involving children than those who do not participate in religious activities. Religion is an important part of research on divorce because the types of social network relationships found in religious communities promote a more positive adjustment to divorce (Krumrei et al., 2007). My findings build on the research of Meltzer (2009), who found that as respondents’ frequency of religious service attendance increased, support for divorce involving children decreased. Based on the findings that participation in church activities decreased support for divorce involving children and Meltzer’s findings that frequency of religious service attendance decreased support for divorce, the religious community’s attitudes toward divorce appear to be reflecting the reality of the effects of divorce. The religious community is beginning to understand the extent to which a young adult’s belief in God and religious teachings and his or her affiliation with religious institutions are affected by parents’ divorce (Marquardt, 2005). The religious community, though, needs to increase their offerings of support for children in a divorce. The General Social Survey question only asked whether or not respondents participated in church activities. The influence of participation in church activities on attitudes toward divorce would be supported better if the question asked about frequency of participation in church activities. Because frequency of religious service attendance and participation in religious activities are good predictors of attitudes toward divorce involving children, religion should 160 S. Meltzer continue to be an important aspect of research on the effects of divorce. Religiosity provides a social network to promote positive readjustment to divorce and serves as an indicator of attitudes toward divorce. The regression model indicates gender and age are good predictors of attitudes toward divorce involving children, and might serve as helpful criteria for research-based divorce education programs. Race and socioeconomic status, on the other hand, are not good predictors of attitudes toward divorce involving children and might not serve as helpful criteria for research-based divorce programs. In addition, the low R 2 (7.2%) indicates that other factors not included in the model could help explain attitudes toward divorce involving children. CONCLUSION I expected men would be more supportive of divorce involving children than women and those who participated in religious activities would be less supportive of divorce involving children than those who do not participate in religious activities. In the bivariate and multiple regression analyses, men were found to have less support for divorce involving children than women. Those who participated in religious activities were less supportive of divorce involving children than those who did not participate in religious activities. Therapists, researchers, clergy, and policymakers have reached two general censuses regarding divorce. First, divorces increase the likelihood of negative medical, legal, financial, social, physical, and mental health consequences for both parents and children (Birch, Weed, & Olsen, 2004). Second, communities have lower crime and poverty rates when there are more intact families than divorced families (Birch et al., 2004). Community marriage policy, mandatory researched-based divorce education programs, and mediation are three possible methods to start addressing our divorce culture. The negative consequences of divorce have created a connection between family structure and social policy in the United States (Birch et al., 2004). Evidence of this movement is “seen in the increase in the number of private, political, and legal movements to strengthen marriage at a community level” (Birch et al., p. 495). The religious community has made our divorce culture one of their top social issues to address through community action. Because a majority of marriages occur in religious settings, religious leaders believe they can do more to “strengthen marriage in their congregations through better preparation and marriage education in their communities” (Birch et al., p. 496). A community marriage policy is a research-based method to lower the divorce rate among congregations and local communities (Birch et al.). A nationwide study conducted by Birch et al. on the divorce rate between counties with a community marriage Our Divorce Culture 161 policy and those without found a decline in the divorce rate in counties with a community marriage policy. Divorce rates decreased by over 2% more per year in community marriage policy counties than in comparison counties. The main implication of this study is that “efforts to change the culture of marriage and divorce at the community level have potential” (Birch et al., p. 502). Comparative studies of children from divorced and intact families demonstrate that children of divorced families have more short- and longterm psychological and social issues than children from intact families (Marquardt, 2005; Wallerstein et al., 2000). Research-based divorce education programs designed to help children with adjustment during and after divorce have demonstrated positive behavioral and psychological results in both parents and children (Kelly & Emery, 2003). Mandatory attendance at a research-based divorce education program would not only provide positive support for children and parents during a divorce, but also contribute to the diminishment of negative effects of divorce on children. Mediation has “created major alterations in judicial practice and continues to be at the forefront of change in family law” (Emery, 1995, p. 378). More couples seeking divorce are turning to mediation because a court hearing or out-of-court negotiation by attorneys can create significant conflict over custody of children and damage negotiations between the parents (Emery). Mediation is based on a structure of cooperative negotiation and therefore can establish a “pattern of polite, structured, and emotionallydistant communication” (Emery, p. 379). Therefore, mediation provides a divorcing couple an environment conducive to conversation at a crucial time when communication typically breaks down. As the key to children’s postdivorce psychological adjustment, mediation allows for “more positive family relationships after divorce, including more equitable financial arrangements” (Emery, p. 378). Research continues to show that cooperative dispute resolution procedures, such as mediation, in comparison to competitive methods of negotiation, such as a court hearing, lead to the best outcome for both parties (Emery). The point at which a couple seeks mediation indicates dissolution of another marriage, but mediation is an effective method for a positive readjustment to divorce for the children and parents. Our current divorce law is not considering the effects of divorce on children. Although community marriage policy, mandatory research-based divorce education programs in each state, and mediation are strong steps toward addressing our divorce culture, our society in general is not getting honest about divorce (Marquardt, 2005). Since the enactment of no-fault divorce, our culture is still turning a blind eye to the negative effects of divorce on children. Once our society gains control of the divorce culture by providing appropriate services, then we can address the deeper social issues such as the imbalance between the demands of the workplace and the 162 S. Meltzer needs of family life. Law follows social change and adapts to it (Friedman, 1984). Although our current divorce laws are a reflection of our evolving social values toward marriage and divorce, a time comes at which we must evaluate our laws and social values in the interest of families and children. That time is now. REFERENCES An Act Revising the Laws Relating to Dissolution of Marriage; Restoring Fault as a Basis for Dissolution of Marriage in Certain Cases; Requiring Counseling Before Dissolution of Marriage May Be Granted, H. 419, 61st Montana Legislature. (2009). Albrecht, S. L. (1980). Reactions and adjustments to divorce: Differences in the experiences of males and females. Family Relations, 29, 59–67. Birch, P. J., Weed, S. E., & Olsen, J. (2004). Assessing the impact of community marriage policies on county divorce rates. Family Relations, 53, 495–503. Block, J. H., Block, J., & Gjerde, P. F. (1986). The personality of children prior to divorce: A prospective study. Child Development, 57, 827–840. Bumpass, L. L., & Sweet, J. A. (1972). Differentials in marital instability: 1970. American Sociological Review, 37, 754–766. Emery, R. E. (1995). Divorce mediation: Negotiating agreements and renegotiating relationships. Family Relations, 44, 377–383. Furstenberg, F. F., & Cherlin, A. J. (1991). Divided families: What happens to children when parents part. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Friedman, L. (1984). American law. New York, NY: Norton. Grana, S. J., Ollenburger, J. C., & Nicholas, M. (2002). The social context of law. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Heaton, T. B. (1991). Time-related determinants of marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 285–295. Hochschild, A. (2003). The second shift. New York, NY: Penguin. Kelly, J. B., & Emery, R. E. (2003). Children’s adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations, 52, 352–362. Kimmel, M. S. (2000). The gendered society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Krumrei, E., Coit, C., Martin, S., Fogo, W., & Mahoney, A. (2007). Post-divorce adjustment and social relationships: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 46, 145–166. Marquardt, E. (2005). Between two worlds: The inner lives of children of divorce. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. Meltzer, S. (2009, April). Our divorce culture: Attitude vs. reality. Paper presented at the Centre College Research, Internships, and Creative Endeavors Symposium, Danville, KY. National Center for Health Statistics. (2006). Births, marriages, divorces, and deaths: Provisional data for 2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr54/ nvsr54_20.pdf Our Divorce Culture 163 Nakonezny, P. A., Shull, R. D., & Rodgers, J. L. (1995). The effect of no-fault divorce law on the divorce rate across the 50 states and its relation to income, education, and religiosity. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57, 477–488. Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (1999). Parental divorce, life-course disruption, and adult depression. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 1034–1045. Thornton, A. (1985). Changing attitudes toward separation and divorce: Causes and consequences. The American Journal of Sociology, 90, 856–872. Wallerstein, J. S., Lewis, J. M., & Blakeslee, S. (2000). The unexpected legacy of divorce: A 25 year landmark study. New York, NY: Hyperion. Copyright of Journal of Divorce & Remarriage is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.