MC Escher Notes Long - 2_13

advertisement

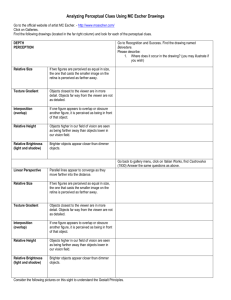

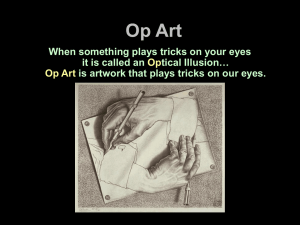

Maurits Cornelis (M. C.) Escher is a well-known and easily recognizable graphic artist. He is most known for his pieces drawn from unusual perspectives creating seemingly impossible spatial effects. Although he is best known for his impossible buildings, visual illusions or paradoxes, and tessellations, he also made some wonderful, more realistic portraits and landscapes during the time he lived in Italy. Escher's work went almost unnoticed until the 1950’s. In 1956 he had given his first exhibition, was written up in Time magazine, and had acquired a world-wide reputation. Among his first and greatest admirers were mathematicians, who recognized in his work an “extraordinary visualization of mathematical principles.” Escher was a prolific artist creating 448 lithographs, woodcuts and wood engravings and over 2000 drawings and sketches during his lifetime. Escher also designed tapestries, postage stamps and murals and illustrated books. Like many other famous artists, Escher was left handed. 1 M.C. Escher was born in Leeuwarden, Netherlands on June 17, 1898. His father, George Escher, was a civil engineer. His mother, Sarah, was the daughter of a government minister. His family (especially his father) hoped he would become an architect, but he did not do well in school except in the areas of design and art. In fact, he never officially graduated because he failed his final exams in secondary (High) school. In spite of this fact, Escher's father managed to get him enrolled in the School for Architecture and Decorative Arts. Escher was enrolled to study architecture, but during his first week of school he showed some of his work to one of his teachers who suggested that graphic arts might be a better career for him. This is what he did. 2 Lithography: The printing and reproducing of drawings using grease-based pencils or crayons on a metallic or stone surface. The artists draws a mirror image (easier & quicker than etching onto a metallic surface). The drawing is first treated with a chemical to set the image. Lithography hinges on the principle that oil and water cannot mix; based on this principle, an oil-based variety of ink is applied directly to the drawing, and the ink immediately bonds with the equally greasy crayon lines. Water is then wiped onto the unpainted areas to keep the ink from smearing. A sheet of paper is then placed over the entire plate plate. The inked stone or plate and the paper are placed in a press and light pressure is used to transfer some of the ink. If the original image was a monochrome pen and ink drawing, this would be the only press run necessary; color lithographs, however, might require several different runs to produce each different color ink. The same paper would be placed precisely over the inked plates, eventually creating a detailed image. This lithograph depicts the village of Castrovalva, Castrovalva which lies at the top of a sheer slope slope. The perspective is toward the northwest, from the narrow trail on the left which, at the point from which this view is seen, makes a hairpin turn to the right, descending to the valley. In the foreground at the side of the trail, there are several flowering plants, grasses, ferns, a beetle and a snail. In the expansive valley below there are cultivated fields and two more towns, the nearest of which is Anversa degli Abruzzi, with Casale in the distance. 3 The Moorish tile work sparked Escher’s interest in creating tessellations. The tiles use geometric shapes. Escher would use recognizable objects and figures instead of geometric shapes. 4 5 Additional examples. 6 "In the horizontal center strip there are birds and fish equivalent to each other. We associate flying with sky, and so for each of the black birds the sky in which it is flying is formed by the four white fish which encircle it. Similarly swimming makes us think of water, and therefore the four black birds that surround a fish become the water in which it swims." M.C.E. 7 Answer: Night turns into blackbirds flying at daylight and day fades into white birds at night. 8 Note: This is a tessellation AND a visual paradox! contradictory things are both true. Paradox: when two 9 Drawing Hands depicts a sheet of paper out of which, from wrists that remain flat on the page, two hands rise, facing each other and in the paradoxical act of drawing one another into existence. Notice the shadow the hands and pencils create on the page as well as the shading that gives the hands dimension. They cuffs have no shadow, nor shading, thus it is “two-dimensional”. 10 Three Spheres, 1946. depicts three spheres on a flat surface. The sphere on the left is transparent with a photorealistic depiction of the refracted light cast through it towards the viewer and onto the flat surface. The sphere in the center is reflective. Reflection is a selfreplicating image of Escher in his studio drawing the three spheres. In the reflection one can clearly see the image of the three spheres on the paper Escher is drawing on: in the center sphere of that image, one can vaguely make out the reflection of Escher’s studio which is depicted in the main image. The sphere on the right is opaque, i.e. neither reflective nor transparent. transparent Hand With Reflecting Sphere, 1935. The piece depicts a hand holding a reflective sphere. In the reflection, most of the room around Escher can be seen, and the hand holding the sphere is revealed to be Escher’s. Self portraits in reflective, spherical surfaces are common in Escher’s work, and this image i the is h most prominent i andd famous f example. l In I muchh off his hi self-portraiture lf i off this hi type, Escher is in the act of drawing the sphere, whereas in this image he is seated and gazing into it. 11 Escher was also a lover of nature. He would often take a break from his sessions in his studio to walk in the woods. These realistic depictions of the natural world are results of his walks and show many perspectives at once. Dew Drop – 1948. Dewdrop depicts the leaf of a succulent plant. The image approaches photo-realism, from the subtle halo of light around the edges of the leaf, to the light from an overhead window being perfectly reflected in the dewdrop. The dewdrop acts as a magnitude lens, which brings into focus the veins of the leaf and the bubbles of air between the leaf and the dewdrop. Dewdrop is one of Escher's pieces that express the geometry of reflections on different surfaces. This piece of artwork is eye-catching and an on-looker must look closely to visualize the detailed reflection within the dewdrop. This image is unique in that from far away it seems simple (a drop of water on a leaf), but up close the details are extremely intricate. Rippled Surface – 1950. While taking a walk one night Escher was struck by the perfect reflection of the trees on the water. He was bending over and looking at the reflection upside down when an acorn fell from a tree and created the ripples. 12 Puddle – 1952. This print is a realistic depiction of a simple image that portrays two perspectives at once. It depicts an unpaved road with a large pool of water in the middle of it at twilight. Turning the print upside-down and focusing strictly on the reflection in the water, it becomes a depiction of a forest with a full moon overhead. The road is soft and muddy and in it there are two distinctly different sets of tire tracks, two sets of footprints going in opposite directions and two bicycle tracks. Escher has thus captured three elements: the water, sky and earth. Three Worlds – 1955.Three Worlds depicts a large pool or lake during the autumn or winter months, the title referring to the three visible perspectives in the picture: the surface of the water on which leaves float, the world above the surface, observable by the water's reflection of a forest, and the world below the surface, observable in the large fish swimming just below the water’s surface. 13 Relativity depicts a world in which the normal laws of gravity do not apply. The architectural structure seems to be the centre of an idyllic community, with most of its inhabitants casually going about their ordinary business, such as dining. There are windows and doorways leading to park-like outdoor settings. All the figures are dressed in identical attire and have featureless bulb-shaped heads. Identical characters such as these can be found in many other Escher works. In the world of Relativity, there are three sources of gravity, each being at right angles to the two others. Each inhabitant lives in one of the three gravity sources, where normal physical laws apply. There are sixteen characters, spread between each gravity source, six in one and five each in the other two. The apparent confusion comes from the fact that the three gravity sources are depicted in the same space. The structure has six stairways, and each stairway can be used by people who belong to two different gravity sources. This creates interesting phenomena, such as in the top stairway, where two inhabitants use the same stairway in the same direction and on the same side, but each using a different face of each step; thus, one descends the stairway as the other climbs it, even while moving in the same direction nearly side-by-side. In the other stairways, inhabitants are depicted as climbing the stairways upside-down, but based on their own gravity source source, they are climbing normally. normally Another interesting fact is that each of the three parks belongs to one of the gravity wells. 14 Belvedere shows a plausible-looking building which turns out to be impossible. The image is of a rectangular three-story building. The upper two floors are open at the sides with the top floor and roof supported by pillars. From the viewer's perspective, all the pillars on the middle floor are the same size at both the front and back. The viewer sees by the corners of the top floor that it is at a different angle than the rest of the structure (its long side faces leftward, while the long side of the middle and lower levels face rightward. All these elements make it possible for all the pillars on the middle floor to stand at right angles, yet the pillars at the front support the back side of the top floor while the pillars at the back support the front side. This visual paradox also allows a ladder to extend from the inside of the middle floor to the outside of the top floor. 15 Ascending and Descending depicts a large building roofed by a never-ending staircase. Two lines of identically dressed men appear on the staircase, one line ascending while the other descends. Two figures sit apart from the people on the endless staircase: one in a secluded courtyard, the other on a lower set of stairs. While most two-dimensional artists use relative proportions to create an illusion of depth, Escher here and elsewhere uses conflicting proportions to create the visual paradox. 16 17