Escher in Het Paleis

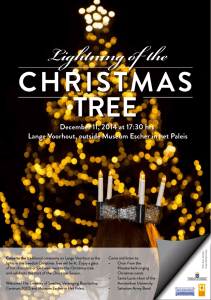

advertisement

Escher in Het Paleis information Index Escher Forever ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Biography........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 The technique behind Escher’s prints ........................................................................................................................ 7 Escher and the concept of tessellation .................................................................................................................... 8 Books................................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Escher Forever Escher in Het Paleis is since 2002 dedicated to the work of Hollands most famous graphical artist: M.C. Escher (1898-1972). Since September 2009 we made a new exhibition with his work: ESCHER FOREVER: a different perspective on the life and work of M.C. Escher M.C. Escher’s prints are based on two main themes: ETERNITY & INFINITY The natural world, perspective and reflection play the major role in the prints based on the idea of eternity. These are subjects that have occupied artists over the centuries. The theme of infinity embraces mathematical principles such as the division of the plane, the multiple facets of stars and planets and the structure of crystals. Eternity and infinity in Escher’s work are usually discussed and presented separately. It seems as if traditional subjects such as nature featured most strongly in his Italian period (1924-1935), while infinity (or mathematics) came to predominate after 1937. Escher for ever: a different perspective on the life and work of M.C. Escher shows that both elements are closely interwoven. In his Italian period the natural world occupied the foreground, but he was still producing fine works such as Three Worlds and Puddle later in his career. He created his first large tessellation in 1922. When he took up this theme again after 1937, nature in the form of birds, fish and reptiles was his greatest source of inspiration. Cycles, circle limits, metamorphoses, perpetual motion and interconnected spaces are the factors linking eternity and infinity. In the last ten years of his working life (1959 to 1969), perpetual motion was the subject of Ascending and Descending, Möbius Strip II and Waterfall. Escher defied the laws of central perspective in Belvedere and Relativity and he connected various spaces to arrive at impossible structures in Other World, Up and Down and House of Stairs. The combination of traditional artistic subjects and specific mathematical insights is key to Escher's work and was very unusual at the time. The mathematical themes go beyond the traditional boundaries of art, but give his prints their power to mystify. He shared these preferences with great artists from the past such as Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer and Antoni Gaudí. In this new presentation we don’t present the works of M.C. Escher in a chronological order, but all the rooms have a theme. In this way we hope to show you Escher has been fascinated all through his life by certain themes. There are special rooms dedicated to nature, perspective, tesselation, cycle and the structure of space by M.C. Escher. The exhibition is completed by an extra presentation about Optical Illusion on the third floor. In all the former Royal rooms we have window screens with information about Queen Emma who lived here during the winter from 1901 till her death in 1934. Room 12 and 13 are dedicated to Queen Emma. All these rooms have also new chandeliers designed by the Dutch sculptor Hans van Bentem. He had them made in Bohemia. The parquet floor in the Palace has been designed in 1991/92 by the American minimal artist Donald Judd on the occasion of the opening of the former Royal palace as a exhibition Palace. The sculptures of Judd consist of series of simple geometric forms, for example rectangular or square cubes in different colours. He believed that art should not be representational: the work should exist as an independent object in its own right. Judd applied the principle of different colours and geometric patterns to the parquet floor in the Palace. In the rooms housing the Escher exhibition the geometric pattern seems to compartmentalise the space. At the same time, it appears logical: the parquet fits naturally into the nineteenth-century rooms, merging into the space. Biography 1898 Maurits Cornelis Escher is born on 17 June in Leeuwarden, in the Dutch province of Friesland. 1903 The family moves to Arnhem. 1912-18 Escher attends Arnhem. secondary school in 1916 First graphic work. 1917 The family moves to Oosterbeek. 1919-1922 Escher attends the School for Architecture and Decorative Arts in Haarlem; lessons from S. Jessurun de Mesquita. 1921 March-May: holiday trip along the French Riviera and through Italy. In November the booklet Flor de Pascua, with woodcuts by Escher, is published. 1925 They live in their own house in Rome from October onwards. 1926 2-16 May: exhibition in Rome. Son George is born on 23 July. 1927-35 Yearly spring trips through inhospitable areas of Italy. 1928 Son Arthur is born on 8 December. 1932 In the summer the book XXIV Emblemata dat zijn zinne-beelden, with woodcuts by Escher, is published. 1933 In the autumn De vreeselijke avonturen van Scholastica (The Terrible Adventures of Scholastica) is published, also with woodcuts by Escher. 1934 Escher’s litograph Nonza is awarded a third prize at an exhibition in Chicago. 12 – 22 December: exhibition at the Dutch Historical Institute in Rome. 1935 In July the Switzerland. Escher family moves to 1922 April-June: journey through northern Italy. In September Escher travels by freighter to Tarragona; trip through Spain and first visit to the Alhambra; on to Italy, where he stays in Siena from mid-November onwards. 1936 April-June: sea trip along the coasts of Italy and France to Spain, where Escher visits the Alhambra for the second time, as well as the mosque in Córdoba. Turning-point in Escher’s work - from ‘landscapes’ to ‘mental imagery’. 1923 From March to June Escher stays in Ravello, where he meets Jetta Umiker. Back in Siena end of June. 13-26 August: first one-man exhibition in Siena. Moves to Rome in November. 1937 In August the Eschers move to Brussels. 1924 In February first exhibition in Holland. Escher and Jetta are married on 16 June. 1938 Son Jan is born on 6 March. 1939 Escher’s father dies on 14 June. 1940 In May the book M.C. Escher en zijn experimenten (M.C. Escher and his experiments) is published. Escher’s mother dies on 27 May. 1941 In February the Eschers move to Baarn in Holland. 1951 Articles on Escher are published The Studio and Time and Life magazines. 1954-61 Each year Escher makes a sea voyage to and/ or from Italy. 1954 In September, one-man exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam on the occasion of the International Mathematical Conference. In October and November, exhibition in the Whyte Gallery, Washington, D.C. 1965 In March Escher is awarded the cultural prize of the city of Hilversum. In August Symmetry Aspects of M.C. Escher’s Periodic Drawings by Caroline H. MacGillavry is published. An article on Escher appears in the October issue of Jardin des Arts. 1966 Scientific American publishes a long article on Escher in its April issue. 1967 Second decoration. 1955 In February the Eschers move to a new house in Baarn. On 30 April Escher is knighted. 1958 Early in the year Escher’s book Regelmatige vlakverdeling (The Regular Division of the Plane) is published. 1959 In November Grafiek en tekeningen M.C. Escher (The Graphic work of M.C. Escher, 1961) is published. 1960 In August exhibition and lecture in Cambridge during an international conference of crystallographers. AugustOctober: sea voyage to Canada. Lecture at MIT in Cambridge, Massechusetts, end of October. 1961 Article on Escher by E.H. Gombrich in the Saturday Evening Post of 29 July. 1962 In April Escher is admitted to hospital for an emergency operation; he takes a long time to recover. 1964 On 1 October Escher and Jetta fly to Canada, where he falls ill again and has to undergo another operation in Toronto. 1968 Exhibitions in Washington, D.C. (Mickelson Gallery) and The Hague (Gemeentemuseum). In July Escher makes his last graphic work, a woodcut. At the end of the year Jetta leaves for Switserland to live with their son Jan. Escher lives on his own with a housekeeper. 1970 In the spring Escher is re-admitted to hospital for another major operation. In August he moves to the Rosa Spier House in Laren. 1971 In December De Werelden van M.C. Escher (The World of M.C. Escher, 1972) is published. 1972 Escher dies on 27 March in the hospital in Hilversum. The technique behind Escher’s prints M.C. Escher was a graphic artist, specialising in woodcuts and lithographs. Woodcuts are made by cutting a design into a block of wood, lithographs by drawing an image on a specially treated flat stone. A woodcut is a form of relief printing: a gouge is used to carve out parts of a wood block leaving a raised image. Ink is applied to these raised parts and then a sheet of paper is pressed onto the inked block. A lithograph is a form of flat or offset printing: the ink is applied to the flat stone and paper then placed on top. In the display case in room 1 you can see wood blocks used by Escher and a litho stone used by another artist (Theo van Hoytema). The various steps involved in making a woodcut and a lithograph are shown here. A print is a mirror image of the wood block or the litho stone. TEMPLE OF SEGESTA Drawing Woodcut Copies can be made of a print. We call this a series. All prints in a series are identical: though the colour may vary, the image or representation is always the same. Escher and the concept of tessellation In these illustrations Escher explained the concept of the regular division of the plane (today called tessellation, or more precisely, isohedral tiling) with a number of variations. Mathematicians and crystallographers have classified these into a total of seventeen different systems, according to symmetries. Escher was not a mathematician: he discovered these systems himself through continual experimentation with new variations. Escher regarded tessellation as his most important theme, a way of expressing his fascination with eternity and infinity in different ways. At the same time, he applied these principles in commissioned work: tile tableaux, inlaid work and wooden balls. Escher produced his first large tessellation in 1922. Later, he found the Moorish tiling in the Alhambra and the decorative Etruscan tiles in Ravello so inspiring that he copied them, sometimes together with his wife Jetta. Books M.C. Escher: His Life and Complete Graphic Work by J.L. Locher, Amsterdam 1981 Een Biografie by W. Hazeu, Amsterdam 1998 (Dutch version only) The Graphic Work of M.C. Escher by M.C. Escher The Magic of M.C. Escher by J.L. Locher and W.F. Veldhuysen, New York, London 2000 M.C. Escher: Visions of Symmetry (new edition) by D. Schattschneider, New York and London, 2004 Escher on Escher: Exploring the Infinite by M.C. Escher, Amsterdam, 1986 The Magic Mirror of M.C. Escher by Bruno Ernst, Amsterdam, 1976 WWW.ESCHERINHETPALEIS.NL Follow us on Facebook and Twitter Copyright © to the Escher prints rests with: The M.C. Escher Company BV, Baarn